Sir Alec Issigonis never dreamed that the small little car that he sketched on a napkin would go on to dominate races and rallies throughout Europe. Throughout the Mini’s design process, decisions were made solely out of utility. Issigonis was tasked with building a car that could transport four grown adults and offer fuel efficiency that could compete with the German bubble cars that were gaining in popularity following the Suez Crisis. While the resulting vehicle fit the bill perfectly, there were a select few very passionate individuals who saw much greater potential beyond the car’s initial utility and efficiency. It was this devoted group of believers that would act as a catalysts for the long and rich motorsport journey that lay ahead for the Mini.

Issigonis attested that the Mini was a car simply meant to transport people along city streets in a safe and enjoyable manner, but it didn’t stop racers from taking the lightweight touring car out on British road courses. Its cute demeanor and small 850cc engine weren’t quite what one might expect in competition, but the same small stature and stance that lent to its efficiency gave the Mini an unmatched nimbleness in the corners. Famous racers, the likes of Bruce McLaren and Jack Brabham, had even adopted the Mini for race duty in their off time. The Mini’s potential was apparent to many, but with a lead designer who still remained skeptical, the underpowered Mini risked falling by the wayside in racing.

Fortunately, there was a dedicated group that truly believed in the small british competitor, and it seems that their efforts all came together at the perfect time to give the Mini the push it needed to reach podiums around the world. On one end, John Cooper, the owner of Cooper Car Company, had been a long time friend of Alec Issigonis, having raced each other in the 1940s Brighton Speed Trials. John watched over Issigonis’s shoulder through the Mini’s design stage. The Cooper Car Company was familiar with the Mini’s proposed A-series engine, having used it to power their Formula Junior and Formula 3 open-wheeled race cars, so they understood what it was capable of when matched with an appropriate chassis.

John Cooper’s proposal to build a Mini for “the boys” at the race track was met with further denial from Alec Issigonis, thus he brought the idea to George Harriman, the Chairman of the British Motor Corporation (BMC). Mr. Harriman challenged Cooper to take one of the production Minis back to his garage and prove to everyone what it was capable of. One of the 997cc engines from their open-wheeled Cooper Formula Junior cars was transplanted to replace the humble 850cc engine, giving it the bit of kick that was needed to place it ahead of the pack. Lockheed, at the time, was developing disc brakes that could fit behind a wide array of wheels, so John Cooper presented them with the perfect challenge : fitting a set of disc brakes behind the 10-inch wheels that adorned the Mini. The rubber cone suspension had already proven its worth, and when matched with the power to properly stop and go, the Mini was quick to impress. As soon as Sir George Harriman returned from a few laps around the test grounds, he inquired about putting them into production. Despite initially being hesitant by the homologation requirement to produce 1,000 cars, he made the right decision. They began producing these new “Mini Coopers”, and went on to sell closer to 150,000 of them.

While John Cooper pushed for the cars in circuit racing, there was a group of racers in Abingdon that were campaigning from the rally side of motorsports. The BMC Competition team hadn’t had much luck with the 850cc in the 1960 season, and many of the guys were less than enthusiastic about the “unique” car, but towards the end of the 1961 season, things began to change. In September, the BMC announced the release of the Mini Cooper in conjuction with the Cooper Car Company, and shortly after, Stuart Turner took over as the Competitions Manager to direct the prestigous group of mechanics. Things were beginning to come together. The new Mini Cooper made its debut at the 1961 Monte Carlo Rally, but unfortunately, while running in second overall, Rauno Aaltonen rolled his Works Mini. Despite the abrupt end to its first outing, it was clear that the Mini Cooper was a contender, and shortly after, it would mark its first win in the books. The ladies of the BMC Competitions team, Pat Moss and Ann Wisdom took first place in the 1962 Tulip Rally with the 737 ABL Works Mini, well ahead of the pack with 7 other Minis rounding out the top 8 places in the 1000cc class.

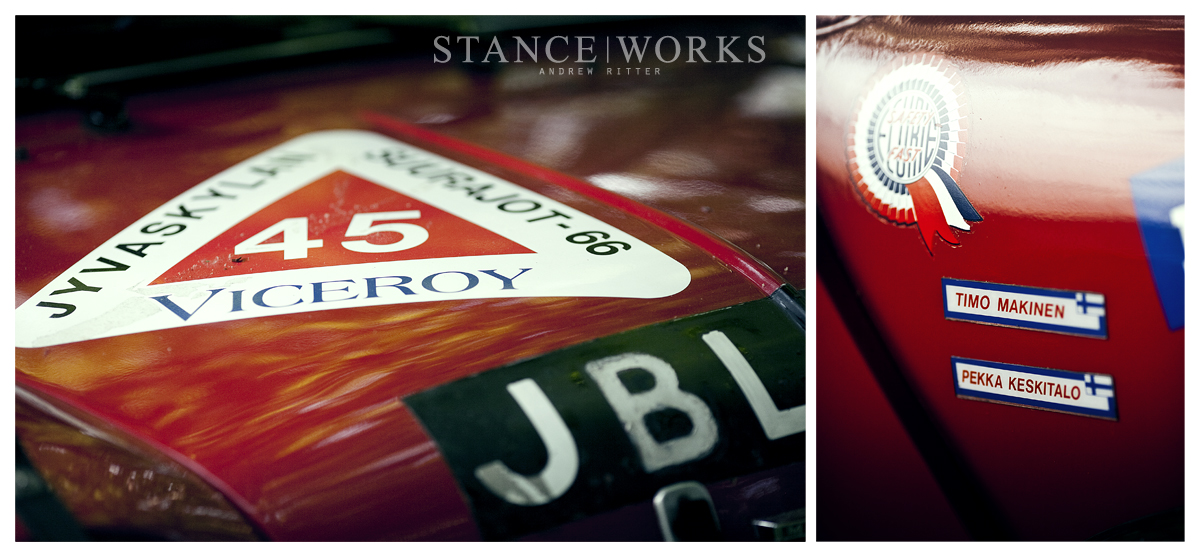

Before long, the momentum of the Mini’s presence in competition was well under way. Through the end of the 1962 season and into the 1963 season, the team received some new blood to add to the already strong lineup. Timo Makinen, Paddy Hopkirk, and Henry Liddon, all joined the crew in Abingdon and their now legendary talents played a vital role in the Works Team’s success. By May 1963, they were already announcing a big-bore 1071cc Mini Cooper S in conjunction with Downton engineering, one of the most respected A-Series performance tuners of the time. The newly bored block, the shorter stroke of the nitrided crankshaft, and nimonic valves improved on the Cooper’s performance, raising power figures from 55 bhp to 70 bhp. The added power was matched by wider 4.5 inch wheels and larger brakes, completing a package that could only improve on the already impressive performance of the Works cars.

Just one month after the Cooper S’s debut, Rauno Aaltonen was racing against the clock in the 1963 Alpine Rally amidst the team of 997 Coopers, and the improvements were instantly apparent. Rauno demonstrated its new prowess by leading the touring car category, and with the help of the other cars, achieved the Team Prize. Through the rest of the season, the team continued to collect accolades, but the crowning achievement for the 1071 S came during the 1964 Monte Carlo Rally. Paddy Hopkirk navigated the 33 EJB Works Mini through the treacherous terrain iconic rally to not only place at the top of his class but to win the competition outright, ahead of the larger capacity Fords and Saabs. The Mini had finally staked its claim in the rally world and proved that behind its small stature was a true competitor.

As the spring of ’64 rolled in, the Mini’s A-Series went through another round of changes. A longer stroke crankshaft increased displacement to 1275cc to fulfill the limitations of the 1300cc class. Now boasting 75 bhp, the newly homologated engine allowed the team to continue their dominance. Having arrived at the perfect balance of engine performace and handling, the Cooper S and BMC Competitions team collected more podium finishes than one could reasonably list, but it was on the road to Monte Carlo that the Mini would earn its place in rallying history.

January 1965 saw yet another Monte Carlo win for BMC, but this time with Timo Makinen behind the wheel and Paul Easter navigating. The Mini had hit its stride, and it looked as if they would complete the hat trick in the following year. Timo and Aaltonen were running in second place with Paddy Hopkirk trailing behind in fifth, separated by a pair of Lotus Cortinas, when rumors began to spread. Under the BMC’s continued and in some ways unlikely success, hostility began to arise amidst the opposing teams. The press could not believe that the Minis were managing to stay ahead of even the hottest Group III sports cars, and people began to question their techniques. Murmurs that certain cars were not abiding by the highway’s headlight regulations had reached the team’s ears but seemed to have no bearing. Undeterred, the Works Minis continued on through the rough course and by the end, the three Minis crossed the finish line in first, second, and third.

As with any race, the winning cars were dragged into scrutineering to ensure adherence to the rules, but what followed has been clouded in controversy ever since. Each time the scrutineers believed they had found a discrepancy, BMC mechanics had to point out that their measuring techniques and guidelines were inaccurate. When the volume of the combustion chambers was called into question, they pointed out that the scrutineers were referencing the old 850cc guidelines rather than those of the 1275cc. When they declared that Paddy Hopkirk’s track width measured 3.4 millimeters wider than allowed, a protest had to be made that the suspension had settled over the 3000 mile course. With careful measuring, it was found that the width was indeed within spec, but when it came time to announce the winners, the Minis had been mysteriously left off of their deserved podium. An hour after the announcement, it was made clear that the cars had been disqualified for supposedly breaking the headlight regulations that had been the subject of prior rumors. In the face of what appeared to be an unfair disqualification, numerous protests were brought up, but in the end they walked away without even a finishing plaque.

In the perfect act of revenge, the Works Minis returned in ’67 and claimed what was rightfully their’s with one last win in Monte Carlo. It was Rauno’s turn at a win. With Liddon at his side, Aaltonen finished 12 seconds ahead of the second place Lancia. They had finally done it. Each driver had collected their own win at the legendary Monte Carlo, and the team had finally earned their hat trick. The car that had once been simply designed to transport families to and from had proven itself on one of the most rugged and treacherous rallies in the world. The Mini would not have been able to reach such accolades without the hard work and dedication of the enthusiasts who truly believed in its abilities from the start. The passion in just a handful of individuals had influence on a giant corporation and it was able to set the ball in motion, allowing the Mini to grow into the iconic vehicle that it is today. Between the team and the cars, the Works Mini Coopers’ story illustrates that even the smallest things can have a mighty impact.