It was in 1985 that BMW decided to make a return to IMSA Grand Touring Prototype racing, otherwise known as the GTP series. After a single race with the aesthetically atrocious March 85G-7 to cap off Daytona and the ’85 season, BMW enlisted the help of March Engineering to build a set of ’86 season winners – the March 86G. The cars possessed what it took to become some of the best in GTP history – immense power, a featherweight chassis, and strong handling. The cars lead the pack… when they maintained their composure. After just a single season, the March 86Gs were retired, two years earlier than initially planned, leaving them to write a brief and unnerving history in the books.

On December 1st, 1985, BMW made their return, albeit an unsuccessful one, to IMSA GTP racing. For the final race of the season, the Eastern 3 Hours of Daytona, BMW entered the March 85G BMW. 11 85Gs were built in total: 8 destined for the GTP series, and 3 built for Nissan’s participation in Group C racing for the World Endurance Championship. Of the 8 that were built for GTP racing, just one went to BMW, and was prepped in a different fashion to its Chevrolet, Porsche, and Buick-powered counterparts. Side-mounted radiators left gaping holes in the sides of the car, and made for alternate aerodynamic characteristics over the others. It was a sight to behold, earning the name of “Donald Duck” due to its unsightly appearance.

The 85G landed itself in the second-place position on the grid with a 1:39.721; however, a failed gearbox would keep driver David Hobbs from finishing the race. It was an ominous hint at the future that lay ahead of the BMW GTP team. Unbeknownst to them, the mechanical failure was an allusion, and without backing from BMW AG (BMW of Germany, BMW of North America’s mother, so to speak), the team was rushing towards the deep end of a murky pond.

BMW had established, with the birth of the BMW NA Works team, that there would be no support from “home” for their undertaking, aside from technical advice and the provision of engines. Instead, it was McLaren that would be in charge of engine development and maintenance to suit their needs, as well as race preparation and assorted technical tasks, as they had with the Group 5 E21s at the end of the ’70s.

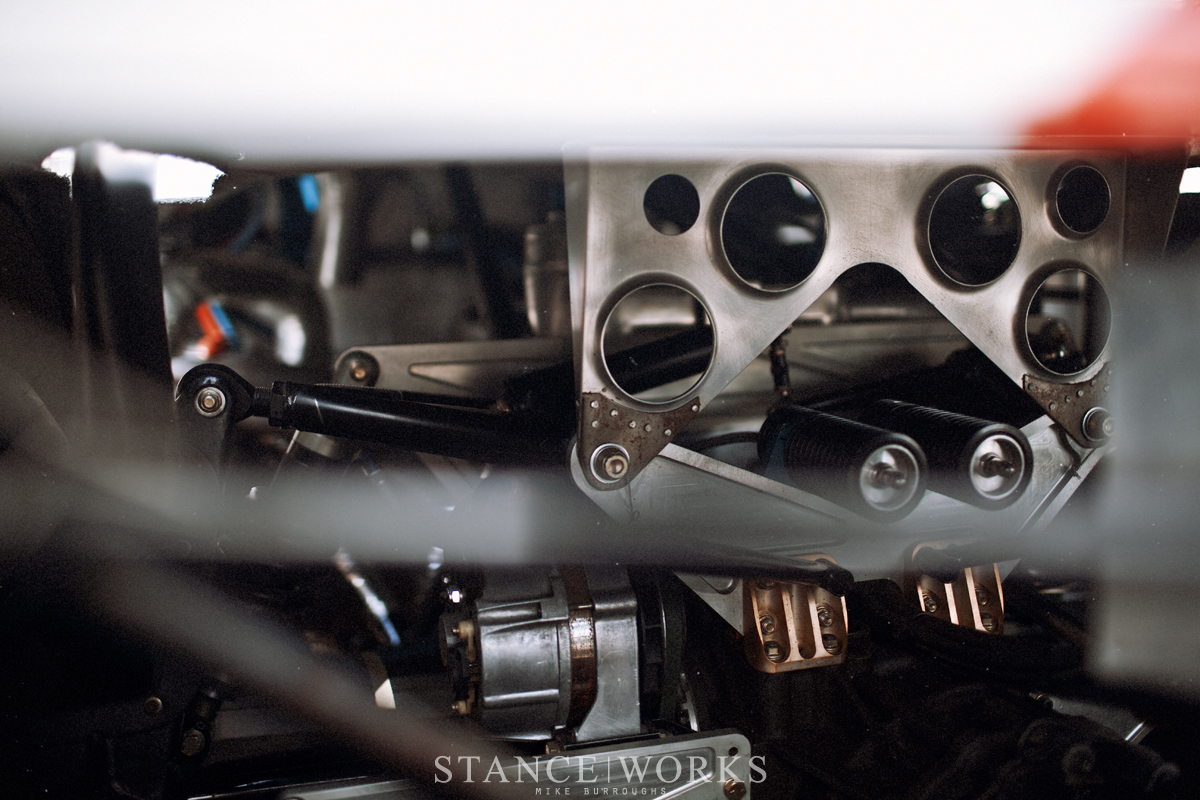

The power plant chosen for the cars was based off of the successful turbocharged M12 1.5-liter engine that powered Nelson Piquet’s 1983 Brabham to a Formula One World Championship title. Upsized to 2.0 liters and powered by a Garrett turbocharger, the M12 pumped out an staggering 800 horsepower at 9000 RPM. In qualifying trim, the engines had been rumored to pump out close to twice that number – 1,400 horsepower – before spewing their guts after taking pole. Compared to its aging 320i counterpart, turbo lag had been greatly improved, but a mechanical nightmare was looming on the horizon, thanks to the BMW team stuffing such a hot-to-trot engine in such a confined space.

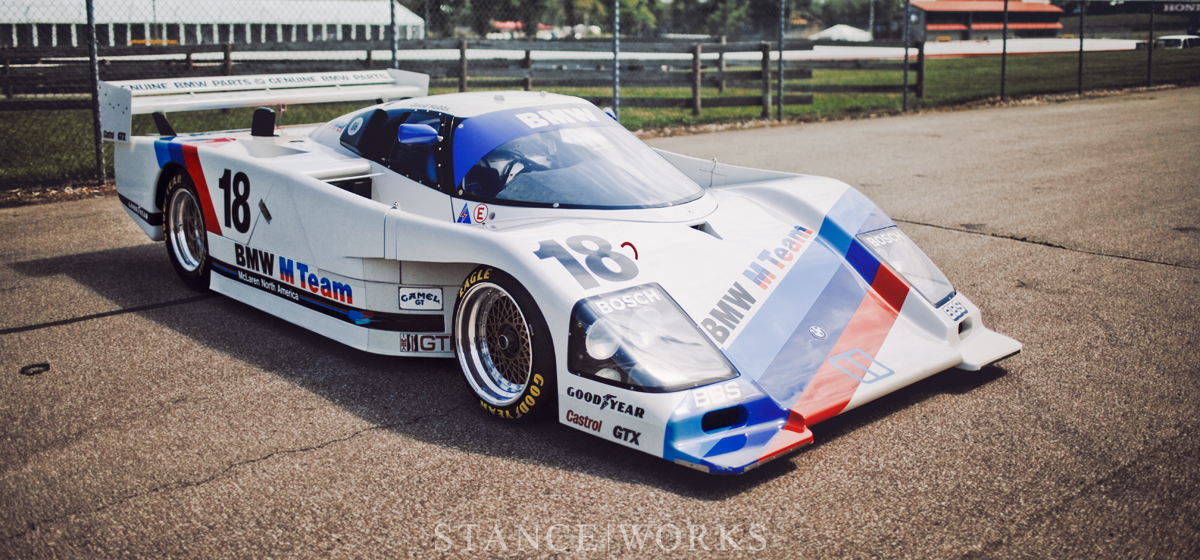

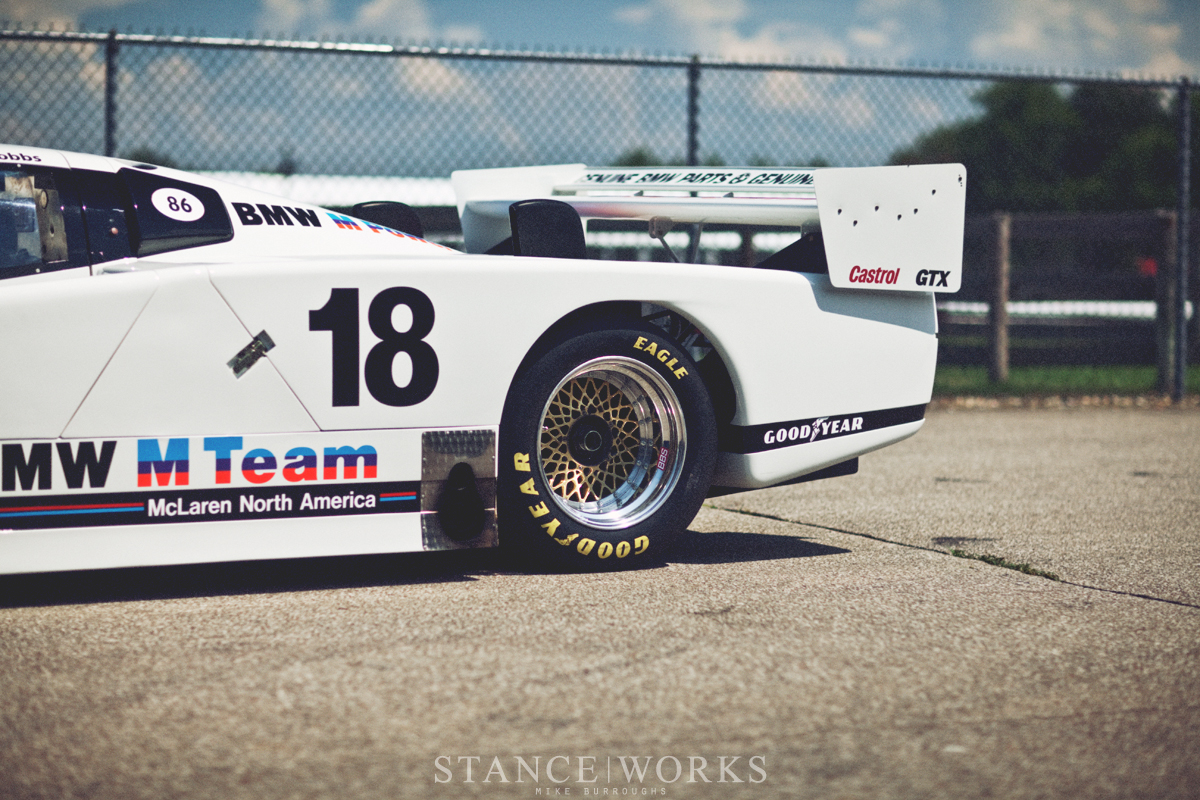

It was clear with the single race from the 85G that the March Chassis and M12 engine combination was a recipe for potential. The 2nd place qualifying lap meant that the car had what it took to win, and as such, BMW went with March once again for the chassis choice. Unsurprisingly, the chassis developed for the 1986 season was justly titled the 86G – a namesake that couldn’t possibly be made more clear. The 86G was born – an 800+ horsepower, carbon fiber honeycomb monocoque chassis, 220+mph demon with an attitude to match.

The 86G was March’s first car to be drawn by CAD, or Computer Aided Design, making it a car of an entirely new breed. Four slightly-different 86Gs, rather titled 86Cs, were built for Nissan to continue their dominating efforts in Group C racing – Chassis 86G-5, 86G-6, 7, and 8. BMW claimed the first four, numbered 86G-1 and so-on. With cars in hand, and drivers ready, the 1986 season preparation began.

The BMW team was planned as a two-car team, following the “junior” and “senior” team layout that BMW had been known for. On the Junior team were Davy Jones and John Andretti, with Kurt Roehrig as their crew chief. On the other was John Watson and David Hobbs, headed by Mark Scott. Bobby Rahal was a final driver on the list, but only briefly.

Hindsight is 20/20, and often better, but foresight is often times clouded by a million variables and the hopes of winning. Other times it is clouded by the smoky haze of a several-hundred-thousand-dollar GTP car set ablaze. The team was off to an unlucky start. By the third race of the season, the team’s count of cars had dropped from four to two. Bobby Rahal’s single race in the car was cut drastically short due to improper fastening of the latches that held down the body paneling. The rear bodywork delaminated, separating from the car’s chassis before catching air and unsettling the car. Rahal took a serious spill, tumbling end-over-end nearly a dozen times. A second car was destroyed by fires during testing, with damage so extensive that the team was forced to write the car off, with no known cause for the fire established.

It was unsurprising that the drivers were hesitant to get behind the wheel for further testing. Tom Klaluser was hired, but his tests proved uneventful, and it wasn’t until John Andretti was back behind the wheel that the troubles returned. A fire broke out during tests for the following race at Road Atlanta. “He was able to get the car back to the pits where they discovered a loose fuel line. Tests showed that the line came loose from vibrations caused by the harmonics of the larger motor. BMW engineers had been aware of the harmonics problem but didn’t pass the information along to BMW NA.”* Two cars had been destroyed thus far, and two replacement cars had been purchased, putting BMW NA further and further into the hole.

BMW put the races on hold. Specialists were brought in to improve the cars – the potential had been seen. When the cars weren’t combusting into radical displays of BMW-Motorsport themed fireworks, or taking to the skies like top-fuel dragsters on launch, the cars were competitive. Six races were passed up until the team returned for the Camel Continental at Watkins Glen in the summer of ’86. The cars survived the race, taking home 5th and 6th place. However, the cars were still plagued with issues. Guaranteed wins were tossed away in the name of mindless issues that simply shouldn’t have been a problem.

“…the engine caused vibration. It simply rattled the car apart. It would break things. It would break subframes. It would break chassis members. It would even rattle fuel lines off. … It caused problems, not so much in the engine but in the car, and mating the engine to the car turned out to be a lot more problematic than we thought,” said Eric Wensberg of BMW North America.*

At Road America, after qualifying first, Davy Jones was sent into the guard rail at more than 150MPH. After his left tires left the tarmac, he lost control, adding to the list of failures and blunders that trailed the immensely fast 86G. David Hobbs found himself leading the same race, demonstrating the capabilities to be found within the machine, yet once again missed his fortune.

[fve]http://youtu.be/H4BUonHSm_k[/fve]

However, the 86G finally had its chance to shine when it returned to Watkins Glen for the Kodak Copier 500 in September. The Junior team, Davy Jones and John Andretti, had lady luck and the Motorsport Gods on their side. For once, the car performed flawlessly. The Senior team suffered from overheating, but it didn’t matter, because what Jones and Andretti had pulled off showed the world what the 86G could truly do. The race was a clean sweep: from pole position, the Junior team massacred the field. The duo set the course’s fastest lap, a feat in and of itself, but that was hardly enough. Instead, the Junior team passed opponent after opponent until the checkered flag was waived and all but two cars in the field had been lapped.

It was a monumental milestone – the first taste of success. But as quickly as it came, it disappeared. BMW announced its plan to withdraw from the GTP series at the end of the ’86 season. The team had hoped for more: the GTP program had been pitched as a 3-year deal, cut short by the fear of the BMW big wigs that knew failing GTP cars with a tendency to burst into flames trackside was a bad image to sell to the public. Despite the potential, and knowing that with further investment, development, and testing that the cars could have been impenetrable force in the GTP arena, the fleet was divided.

Two cars were sold to Gianpiero Moretti, where the BMW engines were pulled and replaced with Buick blocks. BMW retained the two remaining cars, and the campaign was shut down, locked away, and forgotten in many ways. Viewed as a blunder by BMW corporate, and as a shakedown-cut-short by the BMW fanatics, the March 86G BMW is, and always will be, a car the straddles the line between an embarrassment and potential legend. We are confident of the latter.