There’s not a gearhead on the planet over the age of 20 whom doesn’t hold some form of reverence for the McLaren F1 – during its time, it was unquestionably the greatest car the world had ever seen. It was faster and more advanced than any car before it, setting records that are still held to this day. The McLaren F1 was built to honor the late Bruce McLaren and his legacy – it was an exercise to build what could be considered the ultimate road car. Yet Ron Dennis and Gordon Murray had little idea that their project would grow into something much more substantial, eventually concluding with a crowning achievement: an overall win at the 1995 24 Hours of Le Mans, one of the highest honors any car can claim. Suffice to say, in 1995, McLaren ruled the world.

The McLaren legacy extends back to the early 1950s, when 13-year-old Bruce McLaren convinced his father not to part with his project 1929 Austin Ulster. Instead, he pleaded that they turn it into a race car. Bruce got behind the wheel, and within two years, he found himself setting records, his first being the fastest time in the 750cc class of the Muriwai Beach Hill Climb, at just 15 years old. Short-cutting rich history best left to a future article, Bruce McLaren flourished in racing. By 1959, Jack Brabham had invited Bruce to race along side him for the Cooper factory Formula One team, where he won the 1959 United States Grand Prix at the age of 22 years old, the youngest ever Grand Prix winner at the time, and it stood as a record for 40 years. Bruce’s driving skills were apparent; however, driving wasn’t the extent of his skill set. He was as much an engineer and designer as he was a driver, and in 1965, Bruce left Cooper to field his own car and team.

In 1968, Bruce took his fourth career win, this time at Spa in 1968, which marked the McLaren team’s first Grand Prix win – in and of itself a powerful and impressive feat for Bruce, but more importantly, it solidified Bruce McLaren’s name in racing history as one of only two men ever to win a Formula One Grand Prix in a car marqued as his own. McLaren’s creations continued with success. In the mid 1960s, McLaren fielded his own cars in the growing Can-Am series. In 1967, his cars won five of six races, and in 1968, he followed up with four of six. In 1969, however, McLaren had built profound momentum: in the 11-race season, McLaren cars placed first in every single one. In two races of the season, McLaren’s cars took the entire podium, with Bruce himself behind the wheel, as well as Denny Hulme and Mark Donohue. Furthering Bruce’s success as a driver, he piloted, along with co-driver Chris Amon, the Ford GT40 MKII to its first overall 24 Hours of Le Mans victory.

Bruce’s own legacy was cut short in 1970 as he was testing his latest Can-Am prototype, the M8D. The M8D’s rear bodywork separated at speed at the Goodwood Circuit, causing a loss of aerodynamic stability, which sent Bruce and his creation into a flag station, ending his life. It was, by all accounts, a tragic end to a story that undoubtedly would have continued to grow. Despite that, it was merely an end to Bruce’s legacy – not McLaren’s as a whole. Instead, the McLaren name continued, rapidly forging its way towards the top as one of the greatest names in motorsports history. Following Bruce’s death, Denny Hulme went on to pilot the M8D to win 9 of 10 races in the 1970 Can-Am series. McLaren cars won the Indy 500 in 1972, 1974, and 1976. In 1974, a McLaren took the Constructor’s Championship in Formula One, and moreover, it was a McLaren that piloted the legendary James Hunt to win the 1976 Formula One World Championship. Bruce McLaren’s legacy lived on indeed. To date, many of the greatest drivers the world has ever seen are a significant part of McLaren’s history: Niki Lauda, Alain Prost, Ayrton Senna, Mika Hakkinen, Kimi Raikkonen, and Lewis Hamilton.

However, it was in 1989 that the McLaren name took its first significant divergence from the racetrack, leaving the checkered flag behind in favor of the much more familiar red, yellow, and green dangling lights. In 1989, McLaren Cars was founded, and based heavily around McLaren Racing’s Formula One technology and involvement. Three years later, in 1992, McLaren Cars unveiled their first creation: The McLaren F1.

The chief engineer behind the project was Gordon Murray, designer of the 1981 and 1983 Formula One Champion Brabham cars. His initial pitch to Ron Dennis, CEO the McLaren Group, was to build the “ultimate road car,” which was centered around one primary factor: power-to-weight ratio. The McLaren F1 was penned by Murray with a central seating position utilizing a carbon-fiber monocoque tub as its basis, and as such, the F1 was the first production car to feature such construction methods. Carbon-fiber reinforced plastic offered up its strength for the structure of the chassis, while aluminum and magnesium anchor points were grafted with the fibrous monocoque to be used as engine and suspension mounting locations. The McLaren F1 was an amalgam of high-tech elements, composites, and alloys. From the carbon fiber that built the basis of the chassis, to the gold foil that lined the engine bay to deflect heat away from vital components, and even the magnesium that was used throughout for its superb lightweight properties, McLaren spared no efforts in creating the lightest, most efficient, and most advanced car possible.

The car’s atypical layout lends to its performance characteristics. The central seating position, with a passenger seat set to each side, left and right, allowed for even weight distribution in the car’s lateral dimension. Front to back, the car offers a 42/58% weight bias, respectively. Even the car’s fuel tank, located just behind the driver, is centered, and it’s fuel load alters the car’s weight distribution by a mere 1%. Behind the fuel tank lies the F1’s immortalized engine. During the F1’s early stages, McLaren’s partnership with Honda, and their success in Formula One together, seemed to suggest none other than a Honda-powered car. Murray approached Honda engineers with a very specific goal: A naturally aspirated engine that produced 550 horsepower, a weight that does not exceed 250 kilograms, and a 600mm overall block length. Surprisingly, Honda refused. In a twist that would have left us scratching our heads in 2014, the F1 almost ended up powered by a 3.5-liter Isuzu V12, however, the F1 engineers pushed for a powertrain with “proven design and a racing pedigree.”

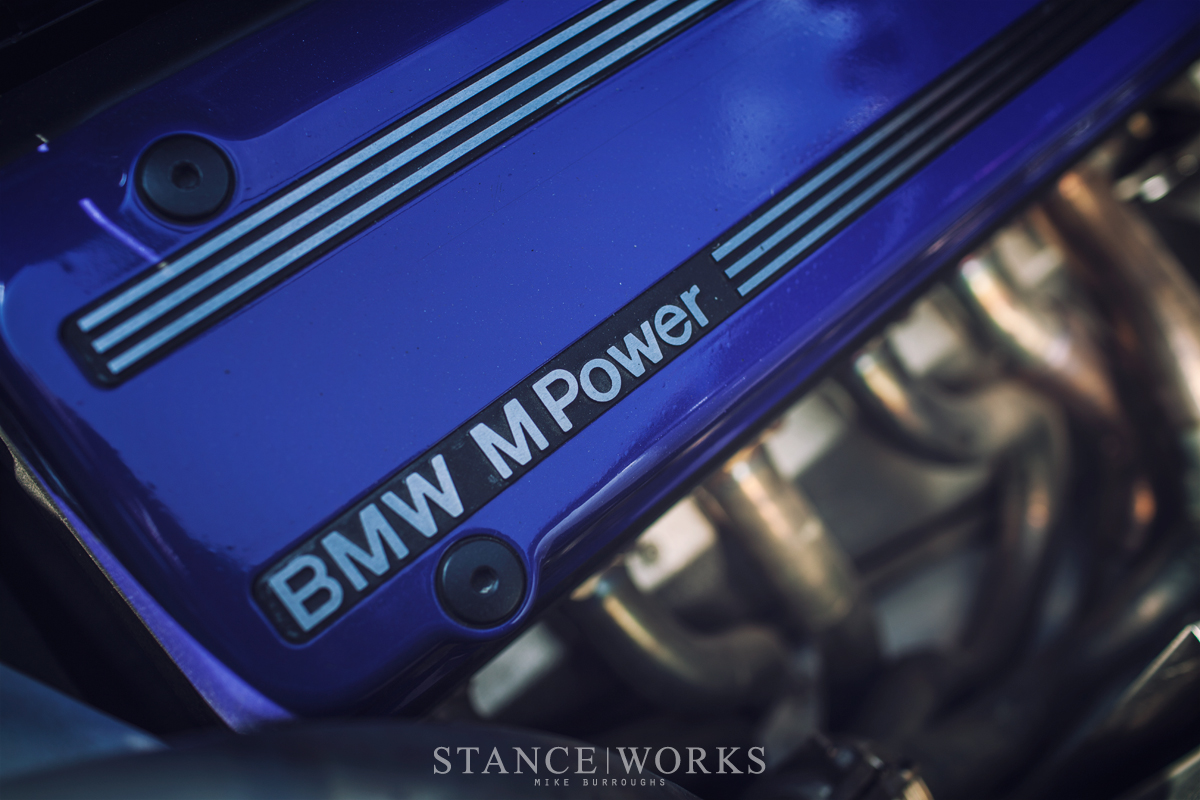

In came BMW to create what is still widely considered the greatest naturally aspirated engine ever built. Known by petrolheads as the S70/2, the BMW M-built V12 is an engineering powerhouse. The 6.1 liter 60-degree V12 pushes out a staggering 627 horsepower and 480 pound-feet of torque. As for Gordon Murray’s standards, BMW had surpassed expectations, bringing 77 extra horsepower to the table, a 14% increase, while only going over the set weight parameters by a minimal 6% – just 35lbs. The almost-all-aluminum engine featured a dry-sump oil system, hydraulic-actuated cam timing adjustments, two fuel injectors per cylinder, 11:1 compression, and a redline of 7500 RPM. That which was not aluminum was cast from magnesium, ranging from the engine’s oil sump system to the engine’s cam carriers and housings, all for maximum weight savings.

Thanks to BMW, the McLaren F1’s final numbers tallied in at 550 horsepower-per-ton, or just 3.6 pounds-per-horsepower. For clarity, that surpasses even the Bugatti Veyron’s power-to-weight ratio of just 523 horsepower-per-ton. Needless to say, the McLaren F1 was alarmingly fast. The stated 0-60 time was just 3.2 seconds, and it climbed from a dead stop to 150 miles-per-hour in just 12.8. In fact, Bruce McLaren’s legacy had claimed yet another record: upon its launch, the McLaren F1 was named the fastest car in the world when it took to the 5-mile straight of Volkswagen’s test track at 240 miles-per-hour, absolutely crushing the Jaguar XJ220’s past record by a mind-melting, face-numbing, and ego-shattering 27 miles-per-hour. The F1 captured the mind and hearts of every automotive enthusiast on the planet. And then it held on for more than a decade.

The McLaren F1 remained the fastest car in the world for 12 years, until Bugatti’s Veyron took the title, but not without the help of 4 turbochargers. In fact, the F1’s record remains, more than 20 years later, as the fastest naturally aspirated car ever built. The raw power, the feats of engineering, and McLaren’s undeniable history in the world of motorsports gave the F1 some serious clout amongst GT racers. Gordon Murray and Ron Dennis had never planned for the car to be anything more than what it was at the time: the best car on public streets. It was never designed with racing in mind; however, pressure came in the form of knocking on McLaren’s door – teams wanted in on the action. Thomas Bscher and Ray Bellum saw the potential of the F1, knowing full well it would prove competitive in the new BPR Global GT Series. After much deliberation, Murray and Dennis gave in, and in 1995, McLaren F1 Chassis #019 was pulled from assembly and modified as a prototype for GT racing, thus the McLaren F1 GTR was born.

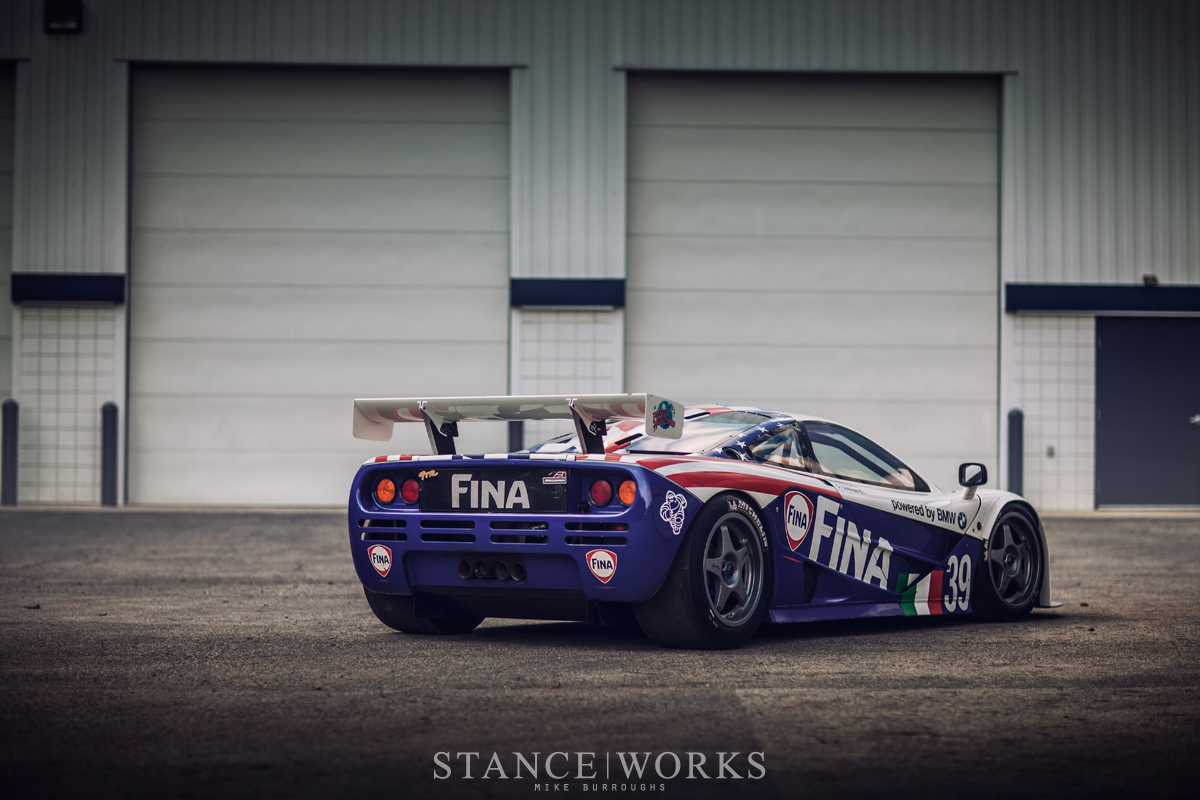

The GTR came in 3 variants – specced for the 1995 season, the 1996 season, and the 1997 season. Changes made to the car were sparingly made, as the car’s inherent construction and DNA were born directly from McLaren’s racing heritage. Aerodynamics were changed slightly with the addition of cooling ducts and a wing over the tail. The interior of the GTR was stripped, revealing the car’s carbon fiber skeleton. The BMW V12 was de-tuned to 600 horsepower to meet restrictions, yet the GTR remained faster and quicker on its feet thanks to a lower weight. The street brakes were upgraded to carbon counterparts, and the car remained largely unchanged otherwise. Nine were built in 1995, and in its first year, the F1 GTR went on to conquer the world, winning the overall victory in the 24 Hours of Le Mans against purpose-built prototypes. It was one of Bruce McLaren’s dreams come true.

In 1996, nine more GTRs were built, upgraded in various ways to remain competitive against a field of new competition. The primary modifications came in the form of a slightly reworked body to improve aerodynamics. A new gearbox was fitted to the driveline, and in the end, the 1996 GTRs weighed in at 38kg lighter than their predecessor. 1997 variants were built, but the 1996 GTR remains the fastest of the GTRs, which brings us to the car before you: GTR #17R.

Only 28 GTRs were built, included in the 106 total F1s built between 1992 and 1998. Each of the GTRs is rich with their own history – some of success, and others of failure. Some were converted to street cars after 1998, and others have been preserved, such as #17R. This car’s highest honors come as an 8th-place finish in the 1996 24 Hours of Le Mans, where it was driven by racing icons: Danny Sullivan, Johnny Cecotto, and Nelson Piquet. Sitting behind the wheel of an F1 was enough to be a life goal, but to share the seat where such legends have been is something I’ll remember for some time. While we can’t all enjoy seat time, spending an afternoon with the GTR lends a special opportunity to StanceWorks – we’re able share the GTR’s story, and to look at it like no one has before. The F1 has done its part to immortalize itself in the top tier of automotive history amongst the informed, but as true enthusiasts, we’re doing our part to make sure no one misses out on the story of such a legend.