While BMW can claim one of the most renowned and prestigious racing pedigrees in history, there is one arena in which their tally falls short. The 24 Hours of Le Mans, the world’s oldest active endurance race, stands as one of the most important races in the automotive world. Also known as the Grand Prix of Endurance and Efficiency, the ultimate in technology, Le Mans Prototypes, race among GT class cars in a battle for the most laps in just 24 hours. With 90 years and 90 events under its belt, the overall victory has been claimed only once by BMW. In 1999, BMW’s V12 “LMR” Le Mans Prototype racer took the win over Toyota by a single lap. And as quickly as it came, the LMR was left to the history books, running the iconic race only once.

The LMR was born as a response to BMW’s failed 1998 V12 “LM” program. The LM program itself, however, was the result of BMW’s own success. The McLaren F1, commonly accepted as one of the greatest cars ever built, retained several production car records for more than a decade after its release. Powered by a 6.1 L 60-degree V12 engine called the BMW S70/2, the naturally-aspirated beast still stands as one of the greatest achievements in automotive history. Powered by a slightly modified S70/2 to meet rules and regulations, the McLaren F1 GTR went on to take the overall victory at the 1995 24 Hours of Le Mans. The cars were raced at the 24 Hours until 1997 when they were no longer competitive. BMW, however, still saw their S70/2 as something potent, and in turn, partnered with WilliamsF1 to build a Le Mans Prototype car for 1998.

After teaming up with WilliamsF1, Formula One constructors champions at the time, to build the chassis and suspension, BMW brought their majestic V12 to the table, utilizing the same S70 as the McLaren, but instead, in a 6-liter configuration. To campaign the car, BMW went to Schnitzer Motorsport, of AC Schnitzer fame. Unfortunately, the partnership was not initially successful. The “LM” suffered from several issues: terrible driveline vibrations lead to BMW pulling both cars from the 1998 Le Mans just 60 laps in. After further testing, it was noticed that the cars suffered from poor aerodynamics and were unable to cool themselves sufficiently. BMW abandoned the LM project and immediately focused on a complete redesign: the 1999 V12 “LMR.”

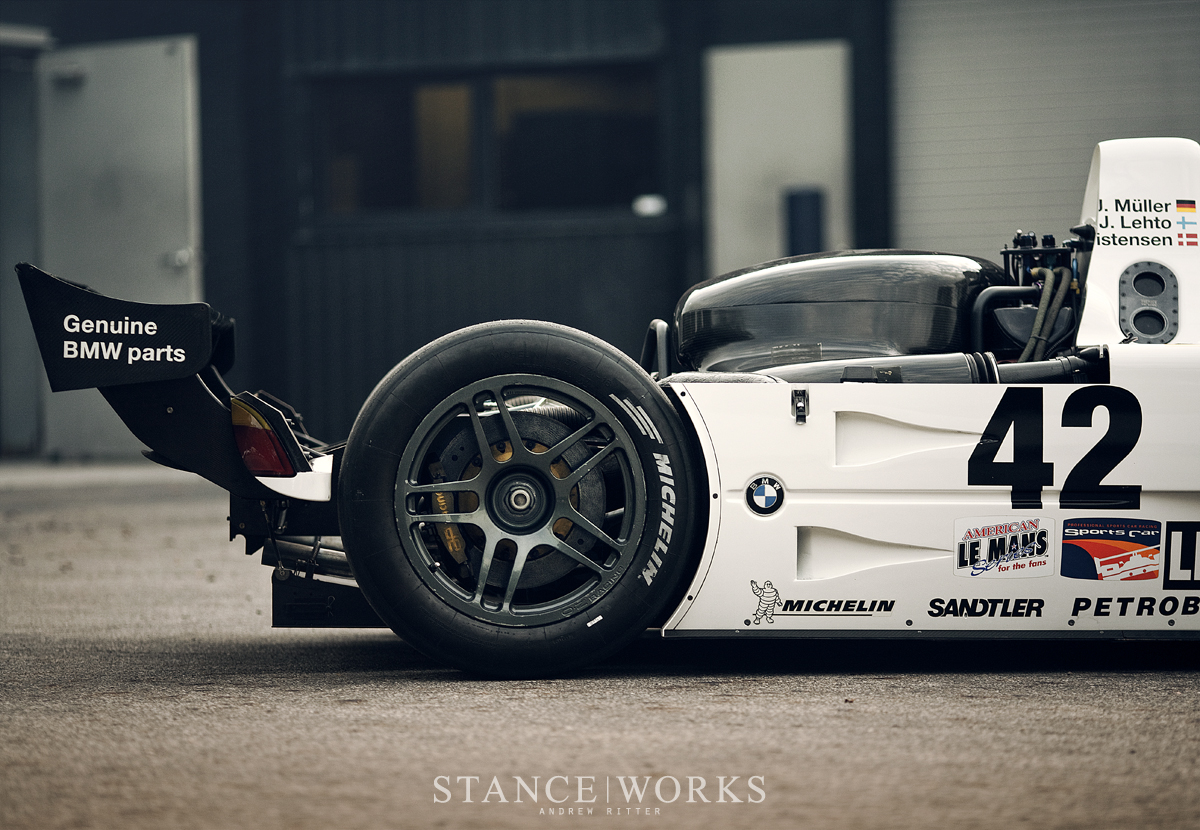

BMW, WilliamsF1, and Schnitzer went back to the drawing board, retaining only the carbon fiber and aluminum honeycomb monocoque chassis for their 1999 revamp; the bodywork itself was redesigned entirely. The primary changes to the car were for aerodynamic purposes. One of the major flaws from the LM was its unorthodox cooling method: air was ducted from underneath the car – a decision that proved to be affected by high ambient track temperatures. To fix this, the LMR featured cooling ducts atop the car. And in a loophole-utilizing decision, the LMR featured just a single roll-hoop above the driver’s head, instead of one that spanned the entire cockpit as the LM’s did. This daring move later became a staple of Le Mans Prototype design for some time to follow. The advantage? Less drag, and less drag means more speed. It also allowed for more airflow over the rear spoiler, granting more downforce.

The engine was retained for the LMR project – now dubbed the S70/3, the 5990cc V12 returned with 590 horsepower and more than 500lb-ft of torque – less than the McLaren road car it once powered due to restrictions on intake and displacement, but enough to push the car to a staggering 214 miles-per-hour on the Mulsanne Straight.. An X-Trac 6-speed sequential gearbox puts the power down to a set of OZ motorsport centerlock wheels wrapped in 36/71-18 Michelin race tires.

Four LMRs were built by Williams, two of which were debuted at the 12 Hours of Sebring, campaigned by BMW Motorsport and Schnitzer as a two-car team. The cars were impressive, devouring the capabilities of their predecessor. The LMR took pole position in qualifying, and the cars lead the pack for the first half of the endurance race. The outcome of the race was bitter-sweet; while one LMR took the overall win, setting the LMR’s legacy off on the right foot, LMR chassis #001 suffered a catastrophic accident – enough damage to seal its fate, never to be raced again.

However, Sebring was merely a shakedown. The team went back to Europe to begin preparations for the race the cars had been built for: The 24 Hours of Le Mans. All three remaining LMRs were prepared for testing, one of which was a BMW Art Car painted by artist Jenny Holzer. The LMR was able to set the 4th fastest lap during the practice session despite the “disadvantage” of an open cockpit. While an open cockpit is more fuel efficient (which can prove to be more important in an endurance race,) the closed-cockpit cars often proved faster in a single lap.

Soon, qualifying rolled around, and two race-prepped LMRs took to the track. A Toyota GT-One managed to take the #2 spot from the LMR in qualifying – BMW knew that the Toyota would prove to be a formidable opponent after their practice sessions, and the qualifying results confirmed their worries. With the #3 and #6 spots confirmed for the grid, BMW and Schnitzer buckled down for the long haul. The first half of the race went as exceptionally as planned: the V12 LMRs held their own against the closed cockpit competitors from Toyota, Nissan, Audi, and Mercedes Benz, whom were all plagued by reliability issues or the victims of accidents.

It wasn’t until the team neared the end of the race that they had their work cut out for them. The #17 LMR suffered the consequences of a stuck throttle, crashing in the Porsche Curves, leaving just the #15 LMR to fend for the victory. Piloted by Joachim Winkelhock, Yannick Dalmas, and Pierluigi Martini, the car would battle head-to-head with the single-remaining Toyota. Although in first place, the LMR was only one lap ahead of the GT-One, hot on the LMR’s tail. However, the racing gods were smiling upon BMW, and the Toyota suffered a tire blowout at high speed. Victory was achieved with a margin of a single lap.

The success between BMW and WilliamsF1 brought BMW into the realm of Formula One once again, providing the engines for the Williams cars. BMW’s decision to focus on Formula One meant that the LMR would not be campaigned in Le Mans in 2000. Instead, the LMRs would compete in the American Le Mans Series, in which they competed but were defeated by Audi and their 2000 Le Mans-winning R8 in almost every round. For Petit Le Mans, the Holzer Art Car was brought back out to make its first racing debut since the 1999 Le Mans Testing, and the 3 cars tried their hardest. However, one car crashed into the side barriers after losing downforce and back-flipping – only the Art Car was able to finish, and at #5, it wasn’t a podium position. The cars were then retired; however, unlike the LM predecessor, BMW chose not to sell off the LMRs to their customers.

And thus, here sits one of the two remaining racers, with chassis #001 destroyed and the Holzer Art Car as #004. In just two years, BMW went from no prototype program to an overall victory at Le Mans, but just as quickly, BMW’s sights changed once again. The BMW LMR is merely a blip on BMW’s motorsports timeline, but will continue to stand as their single Le Mans victory… until the desire to win it arises again.