Levis 501s, Coca Cola, and Hershey’s: successful originals in our everyday lives are easy to recognize. In the automotive world, impacting originals are defined only by their lineage. To point out the original BMW 3 series in a lineup may be difficult for the casual automotive enthusiast. While the E21 chassis is known to some as the “Adam” of the 3 series line, it is better recognized for the bulgy fendered, high flying, tight handling FIA Group 5 competitors of the late 70s and early 80s. Devouring asphalt from Diepholz in Lower Saxony, Germany all the way to Mid Ohio, the 320 Turbo cars were known for their light weight and impressive road holding. Later, the car would emerge as the unspoken test bed of the infamous 1300hp 1.5 liter M12/13 mounted in the Brabham BT52 Formula 1 power plant that vaulted Nelson Piquet to a 1983 championship, the first ever F1 title for a turbo-charged car. As a proud owner of an E21 for half of my life, these purpose built Group 5 cars represent the summit of what the original 3 series was capable of, and as a proud BMW fan, what the constructor could do in motorsport.

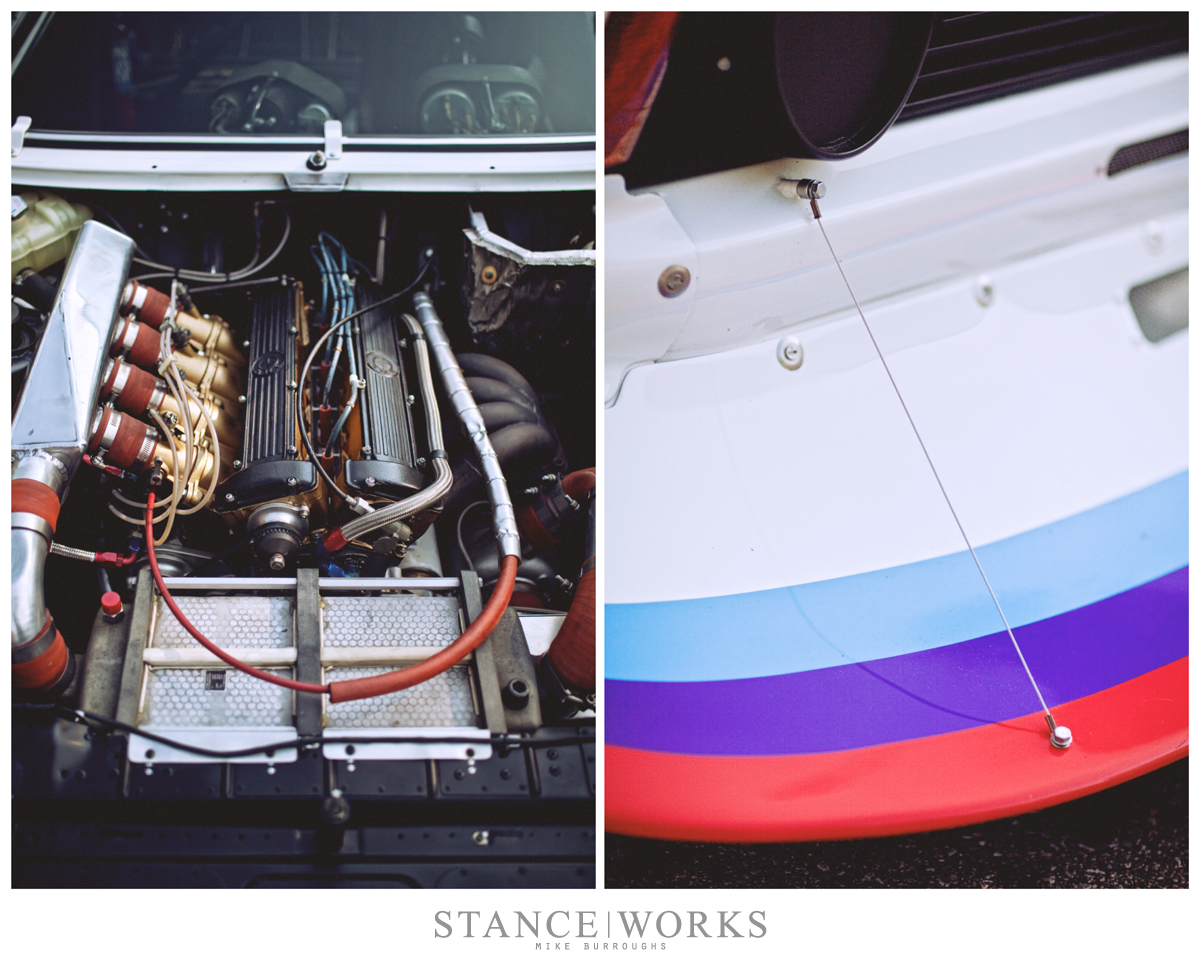

The 4th Generation Group 5 E21 320 Turbo pictured here was campaigned by Team McLaren in the IMSA Camel GT series and piloted by the fabled David Hobbs. The less-than-one-ton chassis housed a 2.0-liter M12 making more than 650 horsepower, which rotated the ridiculously wide Goodyear slicks to unfathomable speeds. With Mr. Hobbs behind the helm, the M12 propelled the car to 7 wins between 1977 and 1978. These victories are quite the monumental feat for an all-new chassis, which saw a change from a naturally aspirated engine to the more complex turbo engine mid-season. The car lacked straight-line speed when compared to Porsche’s 935s and the twin-turbo-charged six cylinder mills found in the rear. Hobbs was quoted “…but we’ll do well in the handling portion of the track. Just could do well enough to make the difference”. Mr. Hobbs was inspired so much by the 320 Turbo that it could almost be credited with inspiring the phrase: “I’ll catch you in the twisties.”

Plagued by reliability issues and growing pains, the car did not race after 1978 in the Camel GT series; instead, it was replaced by the M1. Although the IMSA career was short lived, the Group 5 320 Turbo cars were set loose on racetracks the world over in racing series as diverse as possible. “The Flying Brick” would rocket the BMW Junior Team in 1977 to the DRM championship and remain a long-standing contender in the series before disbanding almost a decade later in 1984. Even to this day, some still compete in European hill climb events, allowing spectators to hear that beautiful music fill the mountain air and reverberate over the tarmac. More important than the race cars resume is the fact that these Group 5 monsters established the pedigree and set the stage for every competition and production 3 series to follow. Rare are the occasions that originals cast such a large shadow.

Although, for me, it’s not the illustrious competition career of the Group 5 E21s that truly excites me. Personally, it’s the fact that finding the original car under the wide haunches, dzus fasteners, and expansive front spoiler is not a difficult task. The production version of the E21 lives beneath the pile of reinforced fiberglass and gobs of horsepower. In fact, the car is almost entirely there. Save the myriad of speed holes and structural support of the roll cage, the heart of a production E21 supplies the backbone of each Group 5 car: BMW Motorsport sold Group 5 kits, complete with suspension and rotating assemblies to privateers that wished to campaign their very own 320 Turbo or N/A cars. With a big enough check, all you’d need to do is receive the shipment and simply supply your own chassis and time. A rather religious experience for me, considering how much time I’ve spent under and around my very own E21 chassis. Even the basis for the M12/13 engines finds its place in humble beginnings. The block is the stock 320i sold at dealers during the decade change between ’70 and ’80.

Sadly, I was not present during the photo shoot of this car; chances are I would have chained myself to the car like an environmental zealot trying to save an ancient redwood, all in an effort to never leave the car’s side. Perhaps it was for the best. To touch and be in the presence of something you hold in such high regard may result in cardiac arrest. Still, to see the pictures and to try and describe what a car like this means to someone as devoted to the chassis is a bit daunting. First and foremost, a wealth of gratitude to the many people of BMW of North America’s Vintage Collection staff for taking such painstaking efforts to maintain and run these fine pieces of machinery. It means quite a bit to fans like myself that automobiles of such historical and genealogical value are under fine care.

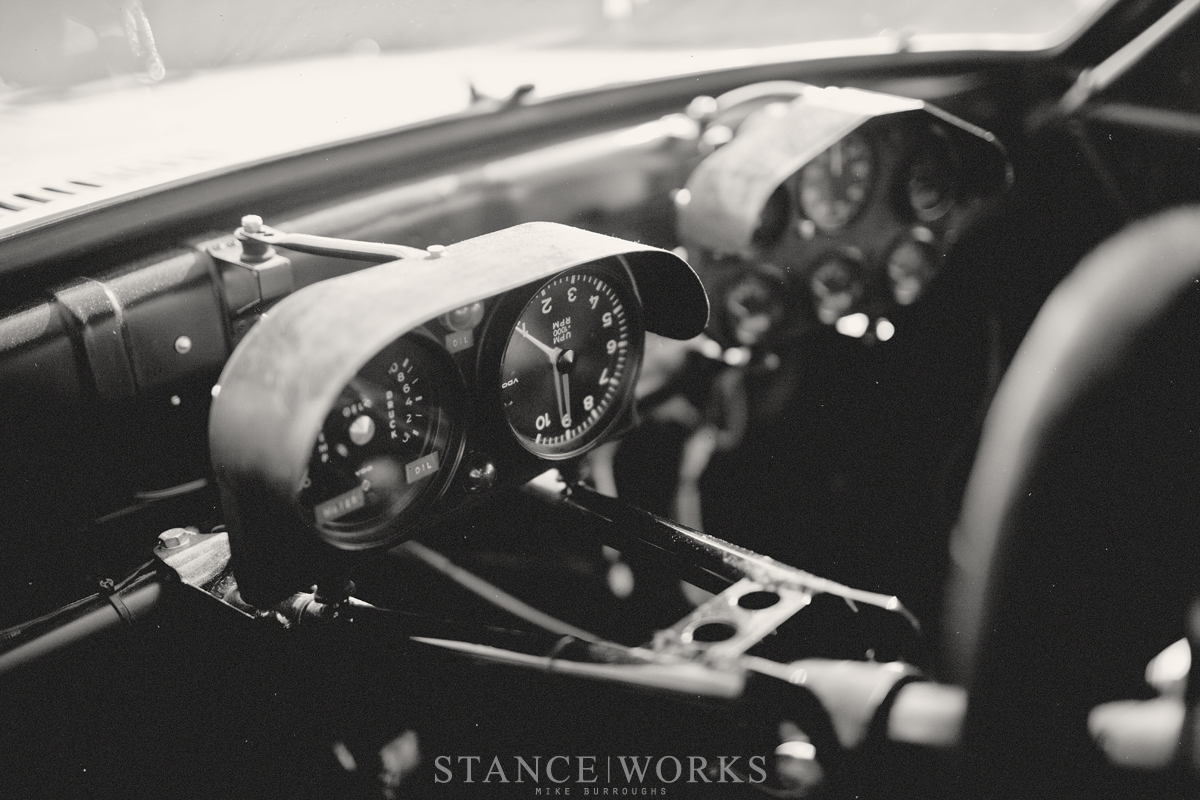

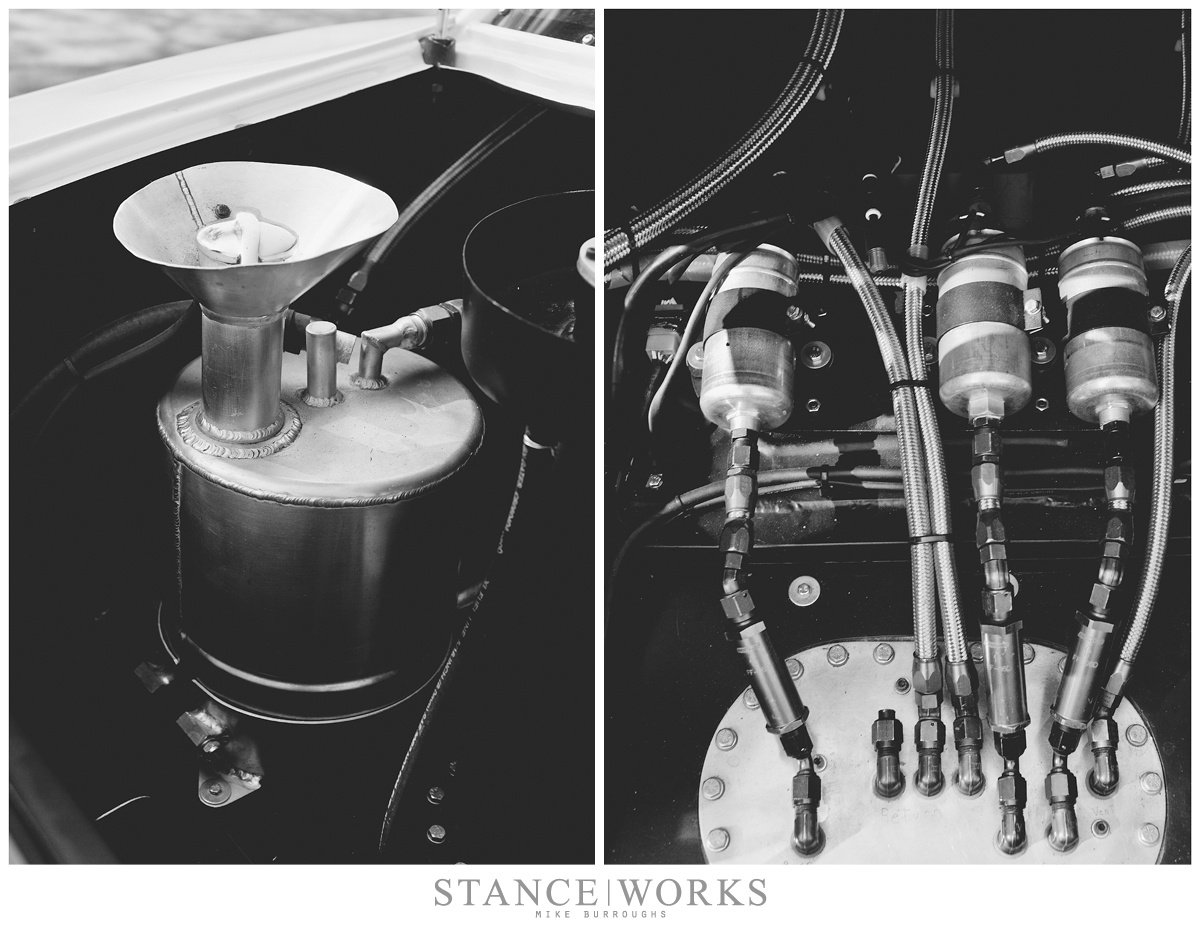

The purpose is undeniable while viewing the car. Within the bounds of the rules, these cars were designed to push the limits of grip and test the mettle of the driver’s spirit. “Hold out a bit longer, brake a bit later, steer with the throttle a bit more.” This petite and humble executive coupe was literally stretched to its limits in the insatiable quest for the checkered flag… and using “stretched” here is no mistake – the car required so much extra space for the supporting parts of the turbo system that each rear fender houses a cooler. Under one arch is a heat exchanger for the engine coolant and under the other is a cooler to compensate for the added temperature in the oil. Not to mention, the massive BBS Motorsport E55s still required room beneath the fenders. Even the alternator found a new home, mounted to the rear of the car and driven off the differential. Every space has been utilized to distribute weight or sequester specific functions of the car to areas that were previously unused.

To this end, McLaren #2 has a peppered number of intake holes and ducting when viewed from the front, and an equally interesting Swiss cheese effect when seen from the rear, giving insight into the consumption of air required to keep the car humming at a steady trot. The massive intercooler and brakes require a constant fresh supply of air to cool the intake charge and battle fading brakes. Speaking of air, the rear wing and the intense “cow catcher” front end, expertly named so after the similar feature found on older locomotives, speak volumes as to the amount of air handling that is required to maintain grip at high speeds. Famous still images of “The Flying Brick” cresting a hill and getting airborne assure us that these aerodynamic bits were definitely not for show.

The juxtaposition of mechanic necessity and beauty captures me with the Group 5 Turbo 320. Making the car beautiful is a function of that backbone I referred to earlier. Being biased for the E21 base model chassis makes loving the race car version so much easier. All the features about the pedestrian car that make the E21 unique have been accentuated by the science to make it faster. The shark nose, which the E21 carries the distinction of being the only 3 series to don, appears that much more dramatic on top of the massive front spoiler. Those rectangular tail lights with blocks of white, yellow and red seem even more at home nestled between the car’s wide hips. An over-fender hood seems more dramatic when pinned as it is here. E21s don’t come more beautiful, or as shocking in figure.

I have the typical boyhood crush on this car. The plastic model has been built. The cutaway poster has been studied at great length. The slot car destroyed after hours of play. Hours spent on Google images and YouTube looking at the car in action. Really, to see one in person and ask questions is all that remains of my humble quest of knowing all I can about the original 3 series racer. Of course, that isn’t the truth. Cars like this never reveal their secrets in entirety and they never cease to amaze those that have a passion for them. Instead this E21 in race trim will continue to peak my interest, and each new photo or video will only provide support and prove that I might have a personal issue.

For my tastes, the car is art. Even without Roy Lichtenstein providing the paint as seen on the Group 5 E21 Art Car, the beauty exists in the connection I feel looking at it, watching it move. It’s my car, my E21 wearing a suit of armor, slicing through the air and turning corners. Shortening the distance between it and the finish line with every centimeter covered. I’d almost like to have my E21 meet McLaren #2 more than myself. I feel like they’d have a good conversation. A couple of real originals trading stories. My only hope is that my ol’ bronze girl can keep McLaren #2 even subtly entertained if such a chance meeting were to occur.