In 1978, BMW introduced the M1, known by many as the godfather of the M lineage. Just 456 cars were built, sold to the public as homologation specials; consumer cars built by BMW for the express purpose of meeting production requirements in order to race the M1. However, the M1 was merely a gift to the public; it was never initially planned for production. Last minute changes to Group 5 regulations meant that BMW was required to produce street versions of their prototype race car if Jochen Neerpash, director of BMW Motorsport at the time, was to ever see his dream come to fruition. The setback meant the birth of the M1 was a troubled one, however, in the end, it led to one of the most unique race cars in history.

Initially planned for Group 5 World Sportscar Championship racing, BMW was shocked in 1977 when regulations were changed, stating that 400 cars must be built to Group 4 specifications before the car could take to the asphalt. However, Neerpasch, the creative mind behind the M1 project, decided that instead of halting the racing program until 400 road-going cars were produced, he would create a racing series around the Group 4 M1. Production of the race cars counted towards the FISA required 400-minimum number, meaning BMW could essentially kill two birds with one stone.

The M1 Procar Championship was born. Neerpasch’s idea was to pit drivers from a variety of racing disciplines against each other. Drivers were pulled from Formula One, the World Sportscar Championship, the European Touring Car Championship, and others. It was no easy task to bring such drivers on board, however. Neerpasch had to call in a favor to the head of the legendary March Engineering, Max Mosely. Mosley’s position as a member of the Formula One Constructors Association meant he had a heavy hand in being able to convince fellow F1 constructors to support BMW. In return, the M1 Procar series could help European Formula One events by racing as a supporting series, pitting the drivers against each other prior to the F1 cars hitting the track at each of the venues.

With the drivers on board, regulations for the series were ironed out. Winners of each race would receive points and a cash prize, and the winner of the series would take home their own M1 road car. While a variety of drivers were invited to race in the series, the Formula One drivers were given the upper hand. The first five spaces on the starting grid were left open for the fastest Formula One drivers of any race weekend. These five would use BMW’s own M1 Procars, while the remaining drivers would race in Procar qualifying races to determine starting positions, and their car were built by privateer teams. While some Formula One drivers were not permitted to compete due to contractual obligations with the likes of Ferrari, Renault, and Michelin, the series brought some of the most recognized names in racing history to the Procar grid. Nelson Piquet, Niki Lauda, Hans-Joachim Stuck, Alain Prost, Emerson Fittipaldi, and Mario Andretti, to name a few.

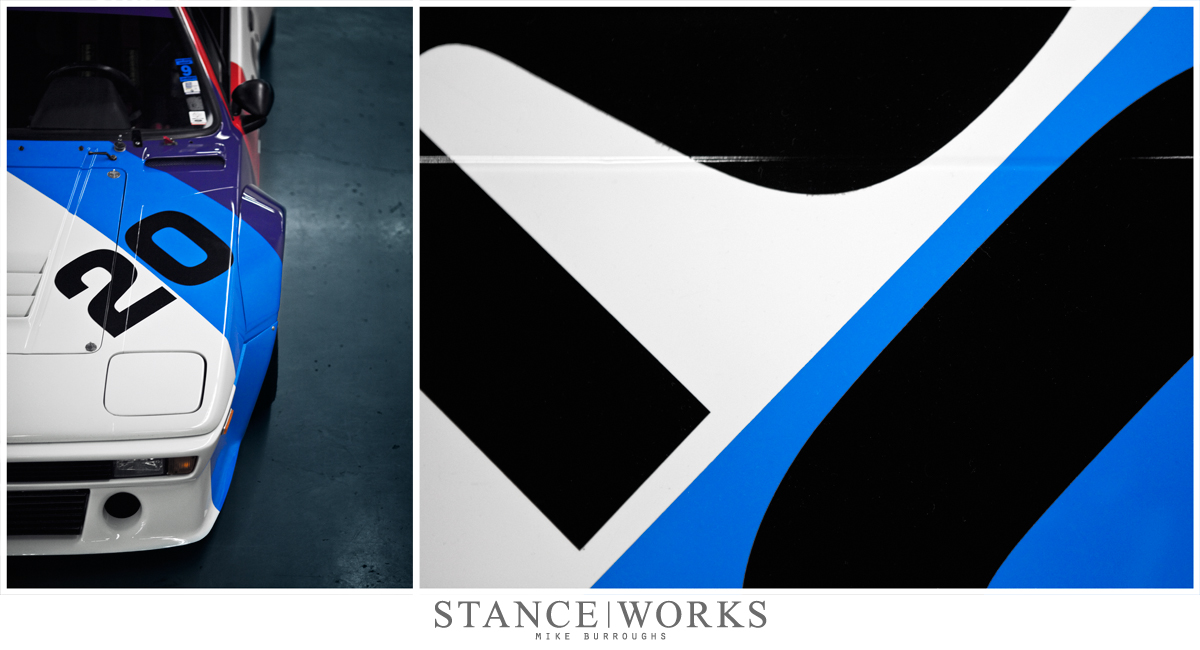

The cars themselves were all built identically. British Formula Two team Project Four, Osella, and Cassani Racing built M1 Procars to compete in the series against BMW Motorsport factory cars. The cars were spec’d to Group 4 regulations, keeping in line with the overall mission of Procar: to aid in building enough M1s to race in Group 5. Surprisingly enough, few attributes were shared with the M1 Procar’s road-going counterpart.

The now-legendary iron block M88, brought to fame by the M1 road car, the original M5, and M6, was modified by Paul Rosche for the Procar series. The cars ran naturally aspirated, and the twin-cam 6-cylinder 3.5-liter engine pumped out an immense 490 horsepower and revved to an ear-piercing 9200RPM. The transaxle from the road cars was kept in place, already sturdy enough to handle the extra load. The suspension received sway bars, new brakes, and an alternate quicker-ratio steering rack. The changes allowed the M1 Procar to hit speeds in excess of 190mph.

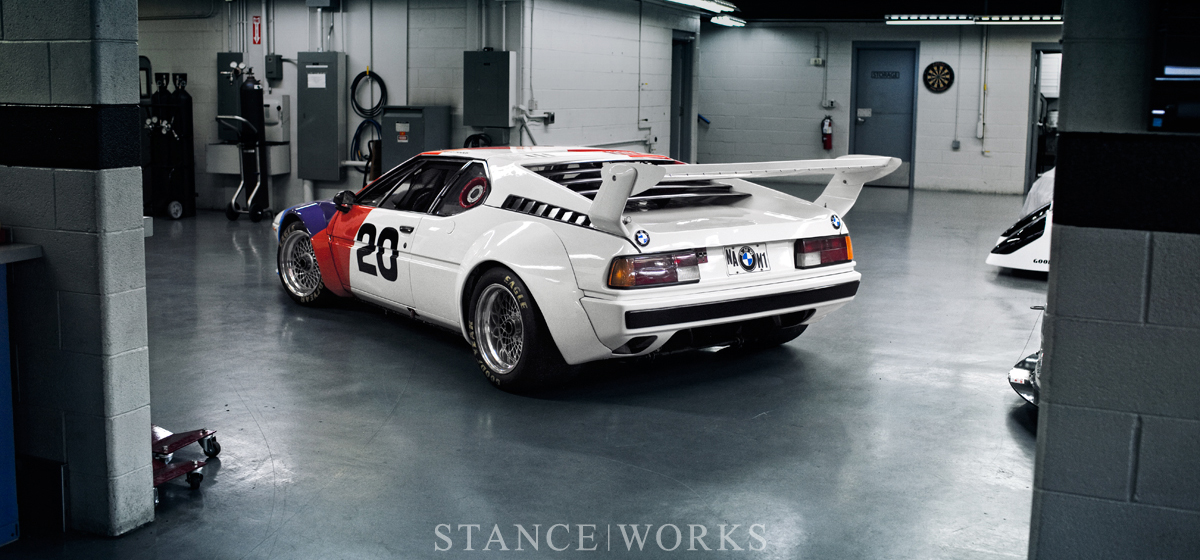

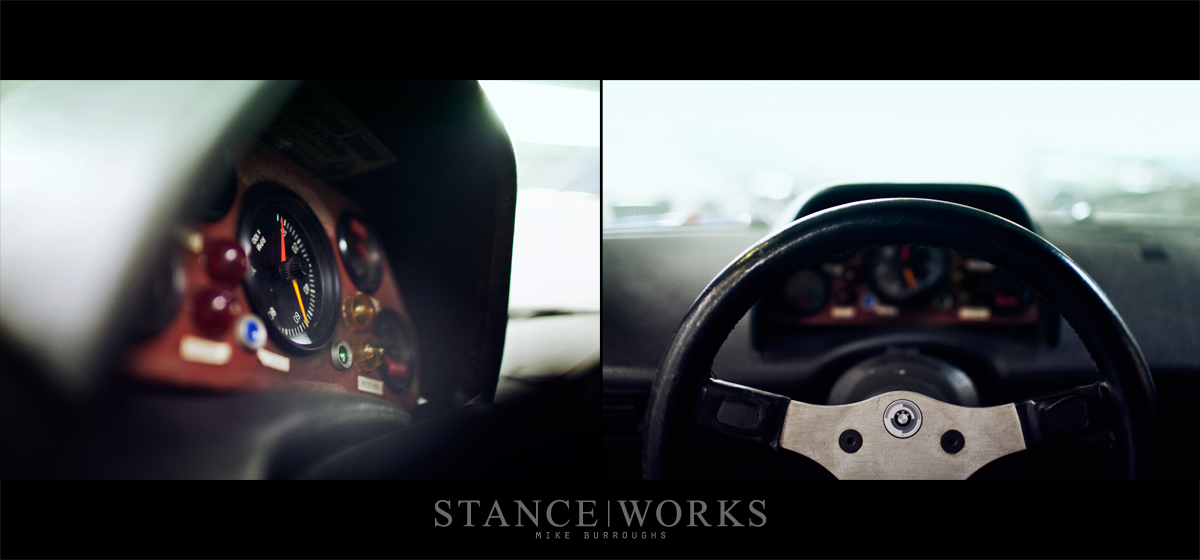

At such speeds, aerodynamics plays a role, so the car was fitted with a large airdam at the nose and a large spoiler at the rear. The arches of the car were fitted with over-fenders to house the massive 11″ and 12.5″ wide wheels. Goodyear tires reaching a staggering 10.5″ and 14″ wide were fitted front and rear respectively. The interior of the car was stripped to the bare essentials, with the necessary readouts providing crucial information to the drivers during the races. The car’s final weight dipped to approximately 2860 pounds.

The racing series went for two seasons, the inaugural in 1979 and the following in 1980. Niki Lauda took the championship for the ’79 series with three first place finishes throughout the eight races of the competition. The 1980 season was won by Nelson Piquet, who won three of nine races, against competing teams such as GS Tuning, Eggenberger Racing, Schnitzer Motorsport, and Sauber. By December of 1980, the M1 finally reached the Group 5 required homologation numbers, meaning the turbocharged 900 horsepower Group 5 monsters could finally be unleashed.

However, BMW was beginning to dabble in Formula One with Brabham, and their focus shifted. Only two Group 5 M1s were built by BMW; others were built by outside sources, such as March, but without a need to meet a required production number any longer, and BMW’s eyes fixated on Formula One, the 1981 Procar season never happened. By 1982, the FISA rules for the M1s were re-written again, dooming the M1 to a history that is summed up by “too little, too late.” A car intended to race in the 70s was never given a chance to truly stretch its legs.

That doesn’t, however, mean it’s a car with empty history. Today, the M1 is widely regarded as one of the “greats”, topping lists as one of the greats sports cars of its time. It blurs the line between supercar and street car, pitting six cylinders against a field of twelve in its era. Its drivability, to this day, remains above any of its competitors, and its Giugiaro-designed body still stands on its own. The legend of the M1 Procar Championship lives on as one of BMW’s achievements, widely regarded as the single greatest one-make championship in racing history. The fusion of the world’s greatest drivers, Formula One circuits, some of the greatest teams in history, and of course, a car that stands as a legend in its own right, leaves BMW with quite the mark on racing.

As BMW enthusiasts, Andrew and I felt honored to stand in the presence of such a car, undoubtedly one of the few remaining and one of even fewer still raced to this day. As part of the BMW NA Vintage Collection, the car is still maintained and raced in historic races across the country. Our one-on-one time with the amazing machine leaves a lasting impression, and it’s truly a shame neither of us were around to experience it in all its glory. However, thanks to BMW, the car lives on, and we’re able to share its remarkable story to those who have yet to learn. Now to get our hands on one…

A special thanks to Bill Cobb, Bobby Rahal, and BMW of North America for letting us shoot the Vintage Collection.