I am sitting in my hotel room right now, thinking about tomorrow, and wondering to myself: “how hard is it going to be to drive a 425hp car, that I’ve never driven before, at Road America (in the wet)… a legendary track that’s made for men with much more talent to run out of than I’ve got to give.” I’ve only balled up a car by my own mistake once. In my younger days, I drove a (it was my aunts car, not mine, I swear) Pontiac Grand-Am through a wrought iron fence into a homeless shelter. Since, I’ve gotten a lot more experience under my belt through a driving school, personal hooning, and a multitude of white knuckle close calls. I’m not positive that much of what I’ve learned applies to tomorrow, which entails driving BMW’s new S55 powered F80 chassis M3 and M4, but I’m here to figure out what the new chassis is all about, and report back to you what I think about the experience. I promised my wife I’ll come home in one piece, and I intend to do just that.

I walked out of the hotel the next morning into the pouring rain. I sat down in the shuttle and began to think about the day ahead. My mind was covered by the fog of morning, and little sleep. “Legendary” is a word that’s often thrown around in the automotive industry – I think its safe to say that there are several marques and models that self identify as legendary and haven’t done anything to earn the moniker. BMW however, has unequivocally earned it. From the late ’80s to the early ’90s, the E30 M3, at a glance, appears to have won almost every race it entered. Without counting and listing off the droves of podiums, race wins, and championships, we can naturally assume they did, and no one is going to argue with me.

The E30 M3 is the father of a tradition that comes only once every 7 or so years. The E30 M3 struck the motorsport world with such force that it changed things for BMW forever. In 1992, BMW introduced the E36 M3. The six cylinder S50 engine in the E36 was a huge leap over the four cylinder S14, and kicked off the (mostly) inline six M3 evolution. Production numbers deeply eclipsed the E30 M3 as the BMW Motorsport division profited from its’ continued dominance of its rivals at the track, and on the street. The E36 eventually gave way to the E46 in 2000 – it weighed 200 pounds more than the E36, and 400 pounds more than the E30. Tradition demanded an increase in power from a new S54 powerplant to carry the increased weight. Other increases were in the amount of technology and computer influence on the driving experience. SMG Drivelogic was now an option, giving enthusiasts the first legitimate way to take shifting manually out of the driving experience. The E90/92 led to a departure from the inline 6. A 414hp four liter V8 that revved to 8300 rpm pushed the 3500 pound car around the streets. Things had again gotten heavier, but fortunately, that is about to change…

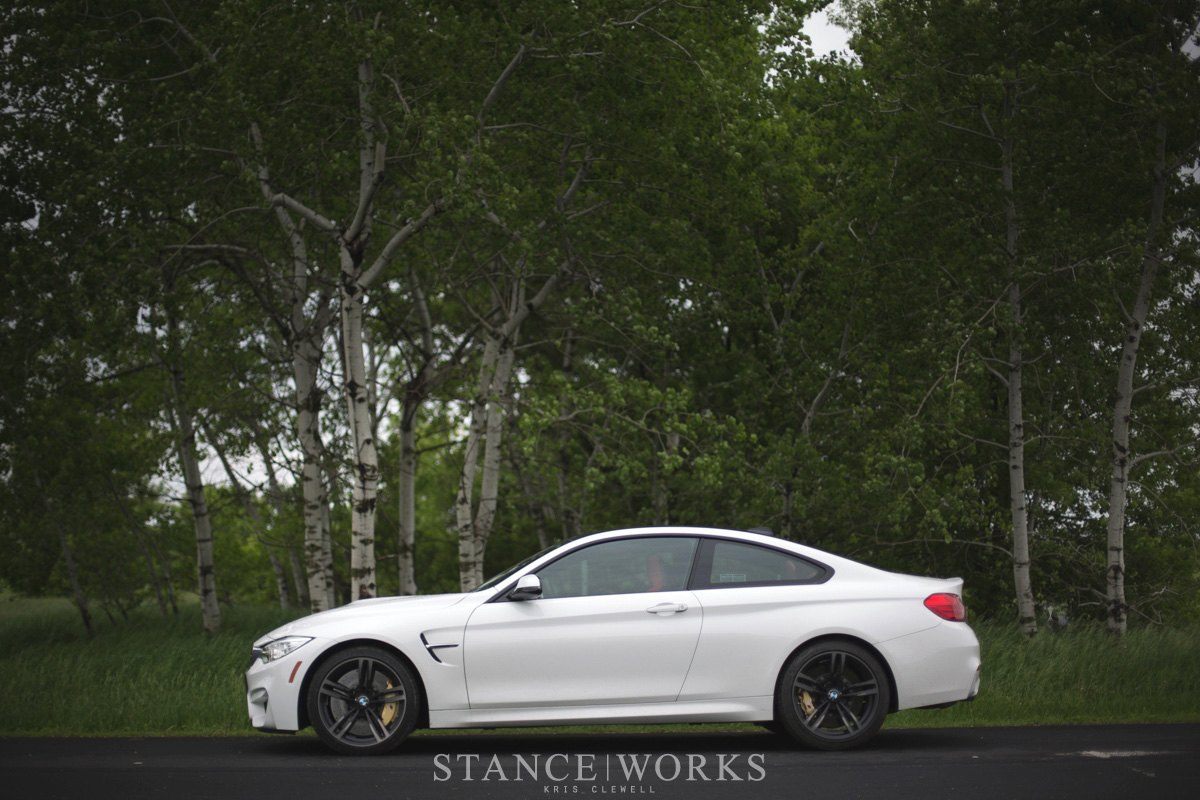

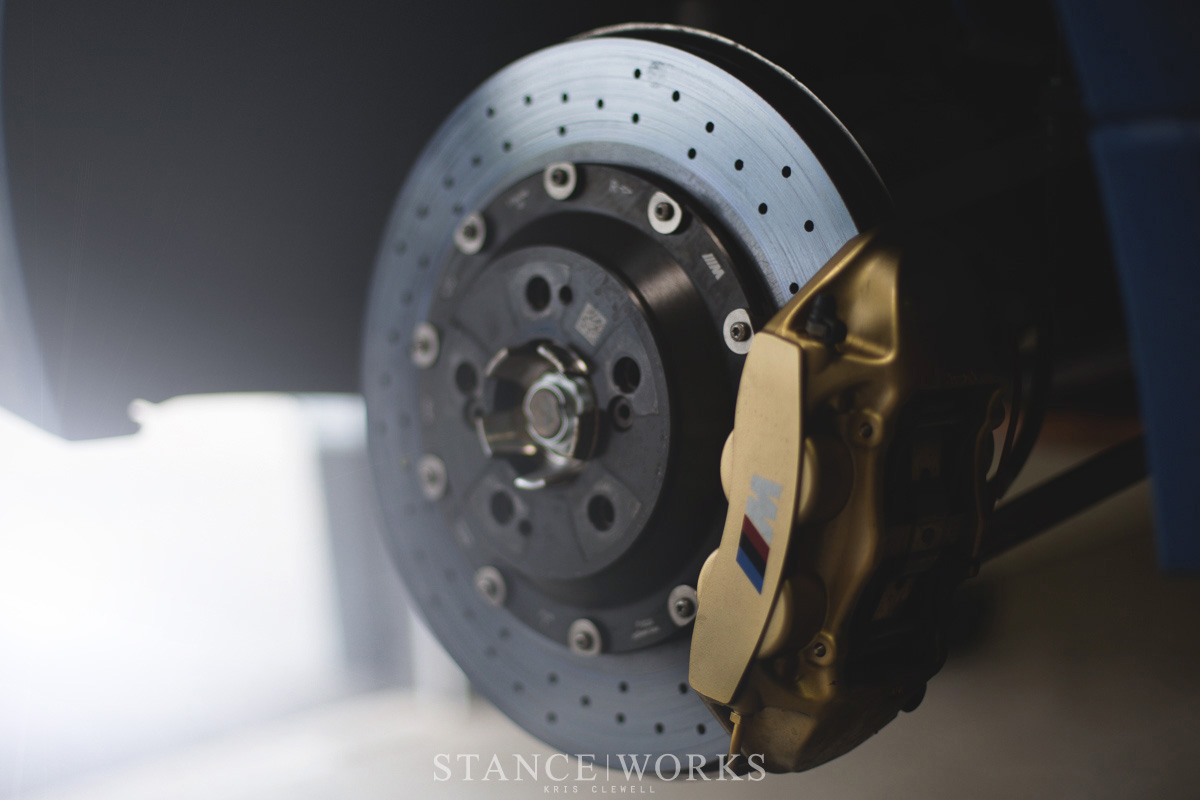

The new F80 chassis: the first of its kind to be lighter than its predecessor. In fact, its lighter than an E46 M3 too. Given a street chassis, power can only do so much; weight reduction makes a huge impact, not only on how the power is used, but how the car brakes, how it turns in, how it reacts to its environment, and of course, fuel economy. The challenge BMW gave to themselves to reduce the weight to E46 numbers was impressive. When compared to comparable competitor models, the F chassis cars come in, at times, up to 500-600lbs lighter. The Audi RS5 weighs around 4000lbs, and the C63 AMG around 3900. The M4 comes in at a prime of its life weight of 3300lbs. One of the reasons I generally steer clear of newer generation cars is the weight, and while 3300lbs is a half-ton heavier than what I like to drive, BMW’s commitment to weight reduction is impressive and refreshing. The new engine is a twin turbo S55, and it’s 20 pounds lighter than the S65 v8 in the previous M3 thanks to smart design features such as a closed deck engine block, coated cylinders, and a magnesium oil sump. There’s weight reduction elsewhere as well: the M4 sports a carbon trunk. Both the M4 and M3 have a carbon roof, driveshaft and carbon strut brace. An aluminum hood and fenders save weight up front along with aluminum subframes front and rear. There’s a brand new forged aluminum five-link rear end bolted straight to the chassis. The efforts to save weight were a huge priority for BMW, and its clear to me that weight is king again.

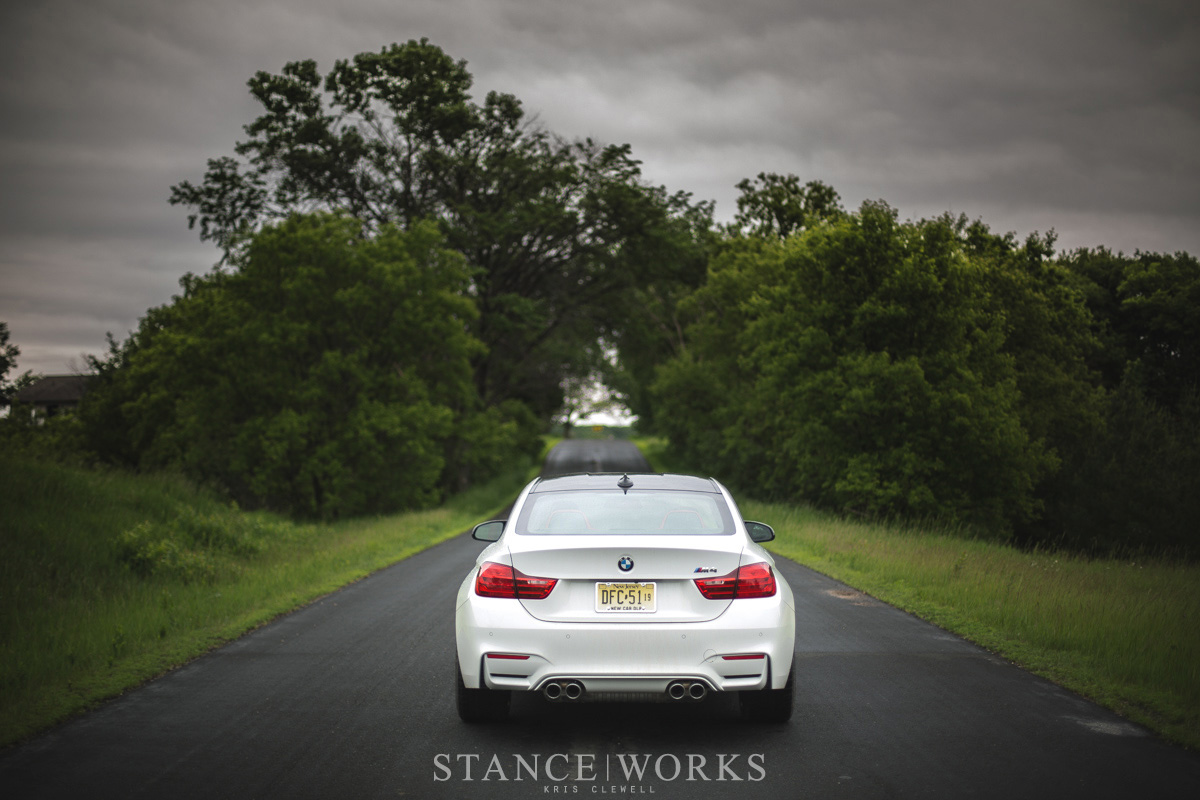

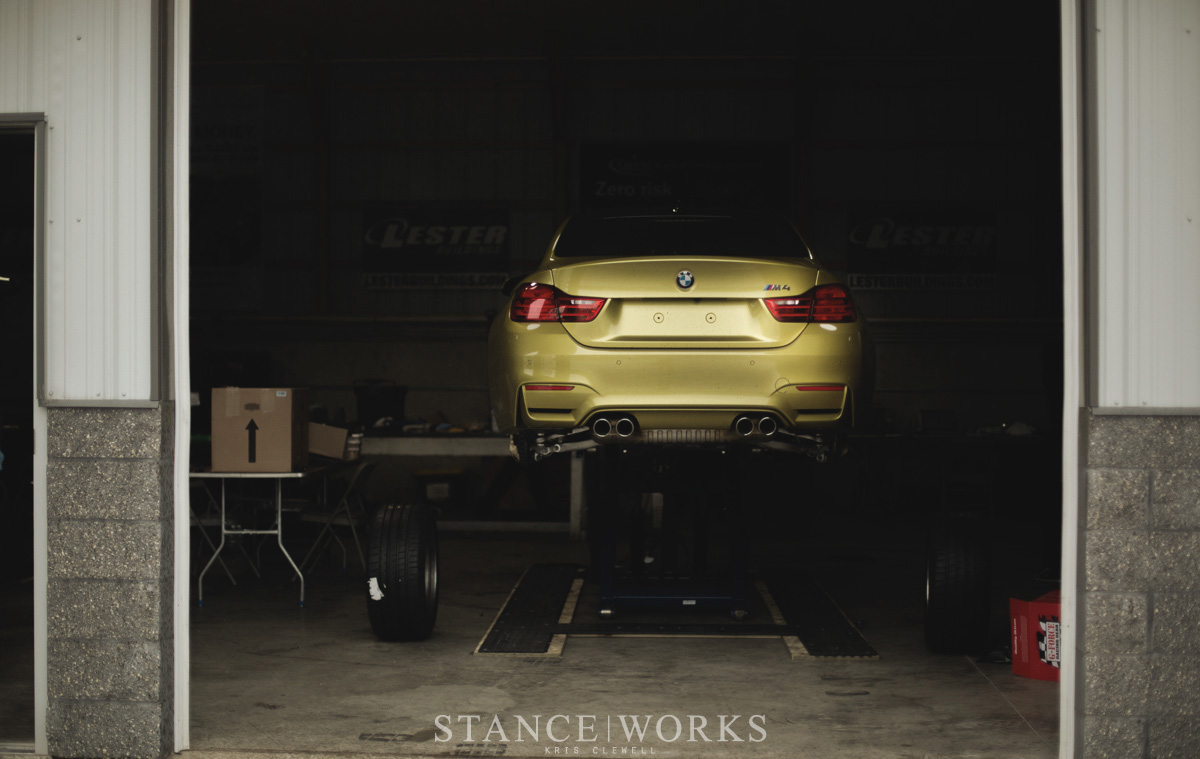

I had been to Road America before, but never for a private event. An eerie desolation was amplified by a steady rain. The shuttle wheeled by empty paddocks, and water rushed, unimpeded, down the curb. With no sense of activity, I was worried. The atmosphere felt dead, lonely. Even from the shuttle, coming up the hill, I could see standing water at the end of the very fast downhill into preceding the sharp left called the Moraine Sweep. I was convinced the event would be delayed or cancelled; sanctioned races have been rescheduled for less. Out the windshield, I caught a glimpse of the west paddock. Amongst people milling about under the motorsport tent was a line of cars in Metallic Yellow, Blue, Metallic Orange, and White. They stood shoulder to shoulder with what I could only describe as a self-righteous spite for the weather that was beating down upon them.

BMW had arranged routes for us to run around the countryside near the track – Elkhart lake is at the foot of Door County. Windy roads and elevation changes abound, and it was a perfect place to see how the M4 chassis handled on the street. One of the things I was most eager to experience was the dual clutch transmission. I wanted to compare it to Porsche’s PDK and BMW’s own manual in the same chassis. The manual transmission performed well, though the automatic rev match when downshifting was a distraction for someone who does it on their own naturally. If you need that, you should probably just get the dual clutch option. It’s tough to say what the real limit was on these cars due to the wet conditions, but I can say that the s55’s torque is immediate and direct, and turbo lag is almost indiscernible. At wide open throttle, the M4 moved with forceful purpose.

With the window down, I wanted to hear the staccato rapping of the engine speaking back from the trees as I wound through the canopied roads. It didn’t. I was stuck with engine sounds being pumped through the sound system. I hate being lied to, and while I understand that a turbocharged engine is quieter than a raging v8, things are what they are, and faking it is distasteful. When the betrayal was out of my mind, the M4 did find the opportunity to speak to me, usually though dings and beeps that I was doing something unsafe. The car was going to roll away, and I needed to make sure it was secure. I opened the hood, and got a warning that it might be hot and that there were liquids under there. Would someone buying an M4 really not know that? I finished up a few shots, and started my drive back to the track. The sensation of speed in the m4 is apt get you into trouble. Several times I found the speed warning nagging in the heads up display. The car inspires unlawful confidence, and was encouraging me to drive ever-harder through the scenic roads. The M4 would undoubtedly make an excellent daily driver, assuming you don’t lose your license.

Back at the track, I knew things were a bit serious when I heard the instructors mention they were taking the kink out of the equation. A slight right on a long straight following the carousel that I always hit flat out (into the wall) on my Xbox had standing water on its right side. Take the kink apex too early and you’re in the wall. Too late, and you scrub tons of speed for the long straight into canada corner. The danger of the kink led track owners to have a bend put in before the kink, which was coned for us. I felt a sense of relief. After the brief safety and technical session with BMW, we were turned loose on the track. I pulled down the pits and leaned to check and make sure I wasn’t pulling blindly into someone as they hammered the brakes and they reeled in their M3/M4 from 140-150mph, preparing for the tough apex just beyond me.

The automatic wipers were flicking back and forth as I pulled onto the straight. I made the first turn, slapped the paddles to get into the right gear, and got on the race line. I had the steering, shifting, and suspension set to sport plus. The steering was immediately heavier. The electric steering is spot on with direct steering and has excellent feedback, a significant improvement over past systems of its kind. Throttle response and shifting was staunch. Downshifting was instant. Power delivery is on demand, and top end power tapers off just around 7300 rpms. The track itself in the wet is nothing short of intimidating. I really don’t want to completely demasculate myself and say I had a sense of fear, but I did. Road America is an old track, and has a few different road surfaces. The transferring from old tarmac to new sent the M4’s traction control into “save the press fleet” mode as the rear end would step out on the change. Two other cars had already been totalled, and I didn’t want to be the cause of the third.

Shifting brought on wheel spin after accelerating from most turns. The shifting, in sport plus mode, was a little too abrupt in the wet, causing the car to slip slightly to the side before the traction control caught on. On the other hand, the carbon ceramic brakes never faded. The brake consistency inspires confidence as you come downhill into sharp turns. I could choose braking points, and know that it would perform the same, lap after lap. I didn’t pay too much attention to the top speed I had down the straight, but it was somewhere north of 140mph. The opportunity to drive the evolution of a legend flat out, at a legendary track, was not lost on me. There’s no time for adrenaline. Concentration was king while lapping.

I’ve driven Road America a million times digitally, and the few things that never translate are the road surface, the elevation changes, and how the rumble strips turn to ice in the wet. I could feel every undulation of the tarmac give feedback through the wheel as I unwound from the corners or worked out the ABS. Consequence for mistakes bred a desire to learn something every lap. The desire to be better, faster, and more confident is something I always knew I had, but the M4 brought it out in me viscerally. Once I got past the gizmos, dings and boops, and once I forgot that the noise wasn’t real, I was able to appreciate the immense talent and investment of resources involved in building the car. The M4 was easily the most aggressive car I’ve ever driven on a track, and the moments I did have where it had dried out some showed me that there is way more available for the experienced driver. I learned this within 10 seconds of riding with pro driver Andy Priaulx. I was shown a distinct difference between us in confidence, ability, and apathy for danger. There’s no question that those guys get paid the big bucks for a reason.

Late afternoon led to dry pavement and the sound of race cars being warmed. Sharp throttles sang short hymns that foreshadowed what would be the highlight of the day. David Donohue’s old E36 M3 PTG race car idled next to Bill Auberlien’s E46 M3. Flanking one side was an E92, and the other, Ray Kormans E30 M3, the car that tallied some of the first wins for the M3 in 1987. Like an orphan with hat in hand, I held my helmet gingerly under the canopy near by, not wanting to miss what was sure to be a small window of a once in a lifetime opportunity. Then it began to rain. The window closed, the cars were shut down, and disappointment took hold. I had a candid conversation with Ray Korman, took his portrait with the car, and headed back to the garage.

By the end of our day with the M4s, BMW needed a car driven back to the hotel, and I was happy to oblige. More time with the car gave me an opportunity to reflect on the day. I’ve always been strict naysayer of newer technology, dual clutch transmissions, 3000lb cars, and other devices that I feel impede my ability to have a rich and rewarding driving experience. It was shocking, going from driving a ‘72 911 to lapping a new M4, but BMW Motorsport has, for the most part, pulled the wool over my eyes, making me forget I was driving a technological marvel. Though not without its faults, the M3/M4 is a car built for people who want to drive, and drivers who want to explore the limits of what’s possible in today’s environment of spoiled consumers, overbearing safety concerns, and industry-altering cafe standards.

In the past, I’ve always said that its more fun to drive a slow car fast, than a fast car fast. And while I still believe this, The M4 taught me that there’s something to exploring limits that are beyond your reach. It broadened my horizons, and awoke in me an alter ego to my old curmudgeonly self. The technology may not be for me, but seeing what’s really possible when a team of brilliant engineers comes together to design on the shoulders of legends is inspiring. The future for the BMW M brand is a bright one.