I’m not entirely sure if I’ve ever actually seen a Chevy Monza on the road. Sold from 1975 to 1980, it’s not entirely surprising, considering it was somewhat of an economy car car built some 45 years ago, and to suggest that the Monza isn’t a pop culture hit is a bit of an understatement. Nevertheless, the Monza holds an important place in motorsports history, following their IMSA GT victories in 1976 and 1977, only to be ousted by the iconic Porsche 935: a worthy opponent, no doubt. The Monza’s path to victory was wildly quick, too, having launched into racing partway through 1975, and securing the class win the following year at the hands of Al Holbert, beating legends such as Peter Gregg, Brian Redman, and Hans Stuck. So, do I have your attention yet?

The story of the most talked about company in recent years, Zemotor, has reached an interesting crescendo.

The Chevy Monza was developed as a follow-up to the Chevy Vega, sharing its base dimensions as a foundation, although history suggest that the Monza itself was produced to utilize GM’s take on the rotary engine. While I’d love to have seen the Wankel platform receive even more support from manufacturers, its no surprise, in retrospect, that the rotary project was canned well before the car was launched to the public. In the rotary’s place, a 350ci small block Chevy V8 can be found, much like many RXs built in the 1970s and ’80s.

Although the Rotary driveline was canned, the Monza still holds an interesting tidbit of trivia in regard to its production: the Monza represents Chevrolet’s first use of Computer Aided Design, or CAD, for development of a production car. In turn, this proved hugely beneficial when race car production was handed off to the team at DeKon Engineering. Founded and led by Lee Dykstra and Horst Kwech, the duo and their team produced a run of tube-chassis race cars for the IMSA Camel GT series. That, of course, brings us to the blue beast at hand: Chassis #1002, the second of 14 cars built by DeKon between 1975 and 1977.

The car was originally built for Harry Theodoracopulos, and made its debut at Lime Rock Park, where it was promptly crashed during its first practice session. The car was returned to DeKon for reconstruction, where it received a few modifications before being returned to race duty. For the ’75 and ’76 seasons, the car raced events at Lime Rock, Road America, Sebring, Road Atlanta, Sebring, Mid-Ohio, Pocono, and Watkins Glen, with a best finish of 9th place at the ’76 100 Miles at Lime Rock. Although #1002 was never an ultimately competitive car, it could easily be reduced to the driver… after all, it shares its DNA with the car that managed to dethrone the 911 that dominated the sport until 1975.

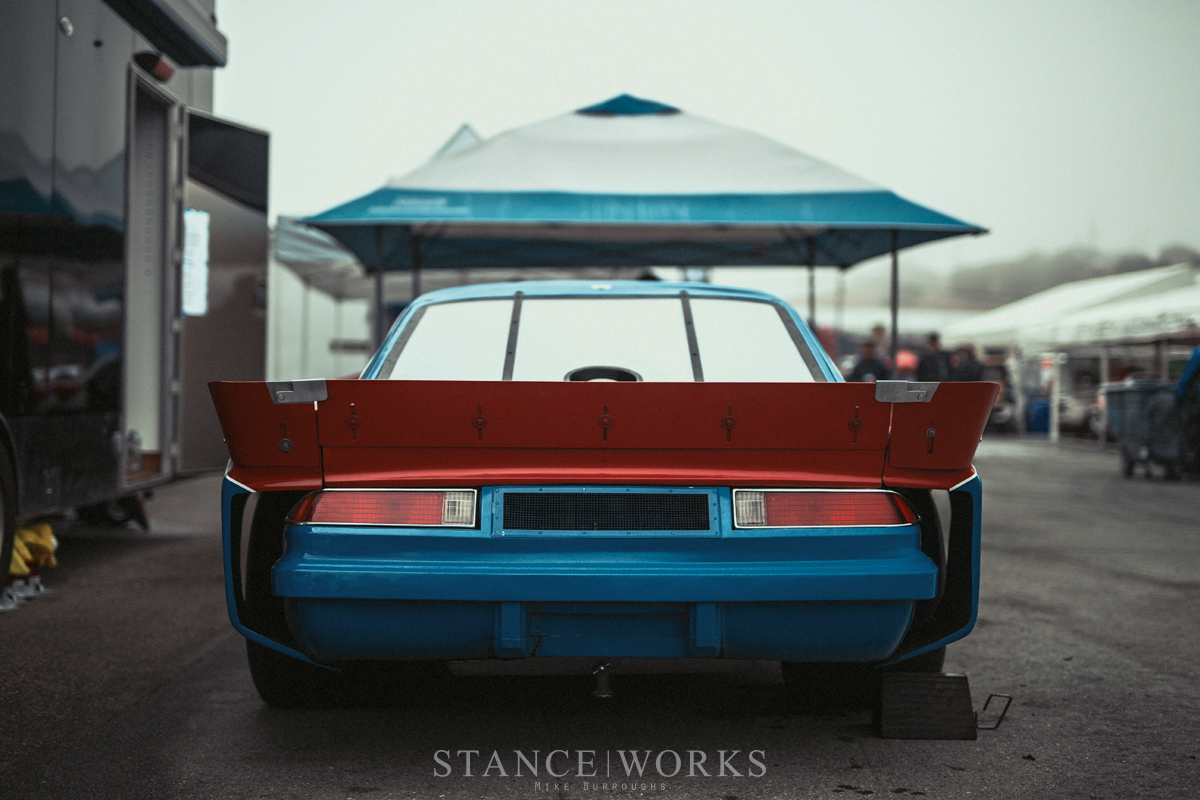

The DeKon Monza platform is defined as a “front engine” car, although a peek under the hood and through the mess of tubework shows that the engine is nested as far back as possible, giving the car a 50/50 weight balance, which is often attributed to its success in IMSA racing. The engine itself is a 300.7-cubic inch Chevy V8, and surprisingly enough, it utilized fuel injection to produce a staggering 650 horsepower and 556 foot-pounds of torque. The power is sent through a classic 4-speed transmission, and out to the massive tires that are housed beneath the extravagant bodywork.

The fenders largely hide the original lines of the Monza itself, blending flavors of FIA Group 5, IMSA GT, and even a tinge of Japanese Silhouette style is thrown into the mix. Its clear from first impressions that the car means business, and it brings the Monza’s road-going disposition onto a whole new plane of existence.

Although the Monza saw continued success in Australian racing, its IMSA reign was cut short by Porsche’s 935: one of the winningest cars to ever see the tarmac. While its reign was short lived, it was well-earned, and has cemented its place in motorsports history as the car that beat Porsche when it seemed all but impossible. Here’s to the Chevy Monza.