We were five or six days into our trip, four-wheeling our way across the Colorado wilderness. As we made our way down the 550 freeway, we descended upon Ouray County’s only stoplight, nestled in Ridgway where the 62 freeway meets the 550. With a town population of less than 1,000, it’s a quiet place, perched at the doorstep of the San Juan Mountains, and was to be our stopping point for the afternoon. We scurried down a dirt road, and then another, with old trucks occasionally parked along the roadside, some temporarily and others as a more permanent fixture. It was reminiscent my hometown in the south in more ways than one, although the absence of the south’s sweltering summer humidity was sincerely appreciated. Eventually, the road narrowed, and all but came to and end. In the clearing sat a sturdy shop, sided by an old home and carport to the left, and a gorgeous airstream motorhome to its right. The shop’s doors were wide open, and behind door number 2 was the nose of a ’71 Datsun 510 laying flat on the ground. This was our destination, and it was a welcome one.

It was clear within a moment that Roddy was “one of us,” the embodiment of StanceWorks at its core. He offered a breath of fresh air in a world of car enthusiasts that continuously seems to be going in the wrong direction. A look around his shop made it abundantly clear: he loves to work with his hands, and a look at his car reaffirms: the build process is both physical and artistic, both creative and mathematic. As a fabricator with the fundamentals of hot rodding running through his blood, I knew his 510 was going to be a treat.

It didn’t take much convincing. Roddy hopped into the 510 and fired it up; the scent of E85 filled the shop, only furthering the sensation of the “builders paradise” he had curated within the shop’s walls. As the car warmed up, he rattled off details and stories, quickly establishing the character of the car he created. When it came time to park the car outside, he revved the SR20 that sits under the hood, and proceeded to simultaneously dump the clutch and stand on the brakes, walking the car to its resting spot with a burnout. One of us.

The story of the 510 begins nine years ago in Silt, Colorado, roughly three hours north. During a visit to Breckenridge, a craigslist search revealed the hidden gem. The 510 wagon was listed for just $2,000, with the original L16 still under the hood. The car was riddled with rust and nearly missing its floor pans, but bits like the BRE-themed spray-painted colorway, some cool 15″ wheels, and a considerable drop thanks to 3″ blocks out back and cut springs in the front meant the car was oozing with style despite its flaws. Roddy was able to see a diamond in the rough, and didn’t hesitate to make the purchase. He caught a ride with a friend, and drove the car home the following day, through the snowy Vail pass without working wipers. It was undoubtedly a precursor for the challenges in the years to come, and Roddy ate it up.

It took some time before the 510 evolved into a full-fledged project. At the time of purchase, Roddy was busy paying a shop to build a Nissan 240SX, which he admits turned out beautifully, but at a cost, of course. While paying for the car itself might have been a questionable purchase, paying for the the lesson it taught certainly wasn’t: “once it was finished I realized I had achieved nothing aside from spending money, and my interest was more in the process of creation than it was burning tires,” he says. The project set off a series of chain reactions and realizations, all helping to define who Roddy is today: furniture pieces, knives, motorbikes, campers… anything and everything, Roddy builds it all within his shop, happily operating on good ol’ word-of-mouth. “I’d say I’m equally trying to learn new skills, as much as I am trying to make money.”

While the 240’s completion helped Roddy realize where his passions lie, it still took some time before the 510 came to fruition as a build. The last time the car drove before its long-term hiatus was in 2010, following a move from Denver to Ridgway. With all of his belongings packed into the wagon, he departed, making it roughly an hour out of town before the sun disappeared behind the mountaintops. Despite his pleads, the headlights refused to turn on. With the help of his friend Erik (as admitted amateurs,) they tried everything they could to get the lights to turn on, but with no luck. Roddy unloaded the car on the side of the road, tarped everything, and slept inside until dawn. He finished the drive the next day, and that evening, ripped the engine out. The project was on.

The car has, clearly, been rebuilt from the ground up. Today, the car sits on what can almost be called a tube chassis, with bits and pieces of the original unibody still remaining as suspension pickups, like the front strut towers. A cage meanders throughout the car’s interior, offering both the protection (as a roll cage should) and chassis support for components like the rear suspension and solid axle. Aside from the front lower control arms, none of the original Datsun components remain. In the back, a shortened 31-spline 8.8 provides the foundation, while a Griggs Racing watt’s link, mounted inverted, keeps it centered. A ’55 Chevy 4-link kit provided the bracketry, while a local rock crawler shop provided the necessary DOM tubing and threaded ends for Roddy to build links of his own. Air Lift Performance E30 front struts paired with Subaru top hats finish it out, making for a rear suspension system that is as custom as they come, and is built to handle any amount of power Roddy decides to send through it.

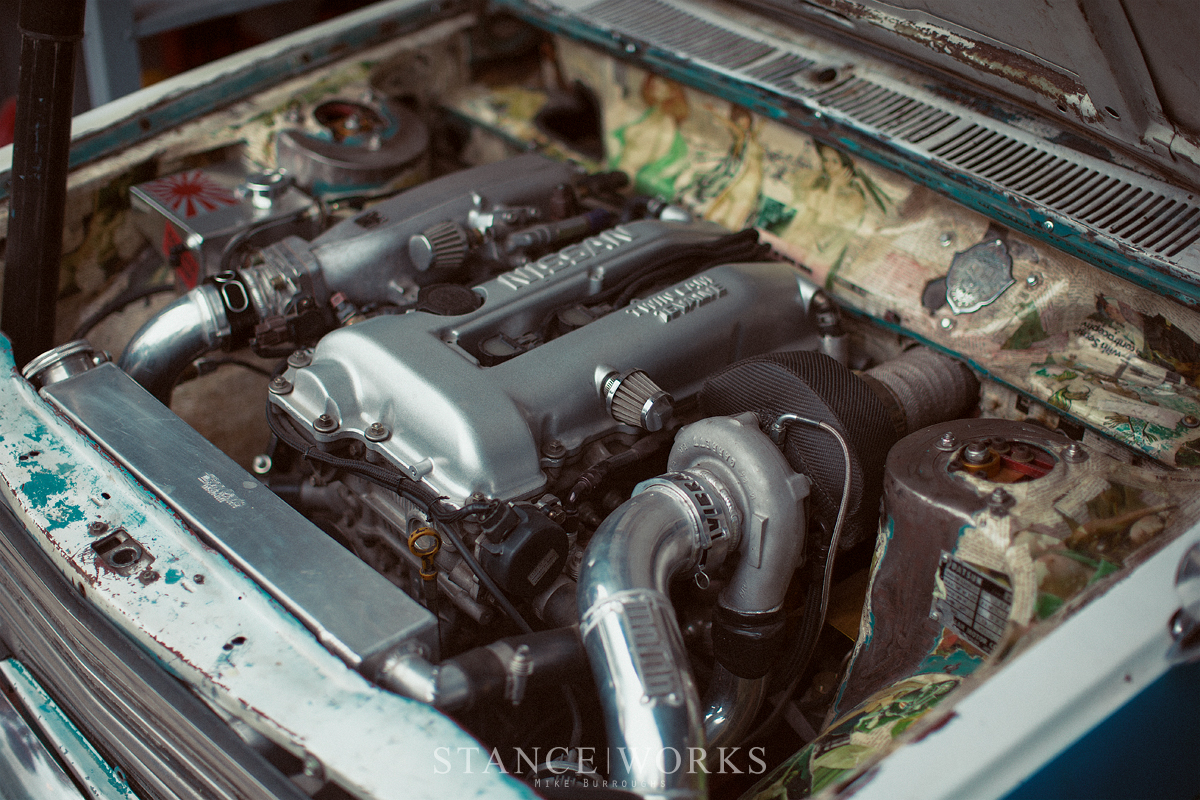

Air Lift Performance E30 front struts also provide the basis for the front system, too. Paired with 280ZX spindles and knuckles, the system mounts nicely up to the car, and with some components like sway bar end links from Kapelhenke Racing, the system as a whole performs well. Discussing the front struts and strut towers brings us to the engine bay, one of the most impressive bits of the car.

Under the hood is an S14’s SR20DET, paired with a Garrett GT2860RS “Disco Potato” turbo for a bump in power, totaling out to 360 horses and 330 pound-feet of torque. Roddy refers to the setup as “basic,” but components like the Injector Dynamics ID1000 injectors, the AEM standalone, or even the gorgeous TIG-welded plumbing itself show that Roddy didn’t sleep when it came to fleshing out the engine build.

Yes, “fleshing out.” At first glance, the engine bay exudes a one-of-a-kind aesthetic, bordering somewhere between “is that paper mâché?” and “is this engine bay a renaissance painting?” However, a closer look reveals far, far more. A slew of 1971 Playboy magazine pages – the same year as the Datsun itself – line the engine bay’s sheet metal in place of paint. “There’s a whole lot of bush in there,” Roddy jokes. Cutouts of women, faces, and words are scattered about, layered effortlessly but perfectly, not just blurring the line between profanity and art, but disregarding it entirely. The decor of the engine bay is second to none; largely faded and illegible, it commands a closer look. At least, that’s what I told my girlfriend at the time.

Inside the car, things are just as rich with character. “Originally I wasn’t really planning on bagging the car, but good ol’ Justin Chenowith basically called me a p***y and the rest is history with that. Once I realized the car was going to lay frame, an entire new list of projects came out of nowhere.” For starters, there was no way to lay frame with a 3-inch exhaust exiting the back of the turbo and going underneath the car. Knowing he wanted something wild, Roddy immediately scrapped the original dash, and started from there. The seats were moved back considerably: 16 inches, to make room for the downpipe. Running straight through the original firewall and out the passenger side fender, a new secondary firewall had to be built to close off the passenger footwell from the hot exhaust piping. The system as a whole stealthily tucks away behind the false floor, and is removed with ease when needed.

Serviceability was an important goal, and despite its looks, the live-edge Walnut dash fits the same bill. With just two main bolts holding it in place, it’s easily removed, as are the switches, thanks to Deutsch connectors on the back side. Only the factory AC vents remain as part of the original interior styling; Roddy turned to his interests in aviation as inspiration for the aluminum switch panels and controls. On the floor below the walnut wood is a set of Wilwood floor-mounted pedals, which required extensive modification to work. He admits the system is a bit atypical, but it fits, and it works.

The car was, of course, built around its wheels: a set of BBS E76s. Roddy says he wasn’t even sure what they are, but the odd ball sizing – 15×8 and 15×10 with serious negative offset – made them alluring and worth the adventure to fit them. It was Roddy’s buddy Mike that originally had them on a Datsun 810 wagon, and Mike’s father before him, which goes to show the wheels’ age, but their provenance is otherwise a mystery. The wheels, in any case, gave Roddy something to aim for, and after clearancing the inner arches and wheel wells to allow for the sizable rubber, he’s got the car laying flat on the ground.

The 235-section width BFGs on the back of the car are larger than Datsun ever intended for, although they’re far from enough to harness the power of the turbo 4-cylinder at the car’s nose. Combined with the wagon’s relatively low weight, it makes for a bit of a riot behind the wheel. “It’s slightly overpowered,” he jokes. “None of the switches are labeled, either. It’s a deathtrap.” That’s not to say, however, that the car doesn’t drive well. In fact, Roddy touts that it handles quite well, and is more than solid underneath, leaving no fear of breaking things no matter how hard he hammers on it. It drives straight and true, and is geared well enough for long highway drives, if and when he decides to bring enough E85 with him.

The car clearly turned out as something wildly unique, and with a truly special presence; however, it’s clear, as it was with his first 240SX, that it wasn’t about the finished product, but about the journey. Roddy says “I’m pretty confident this car taught me more than anything I ever learned in school, including going to an automotive based vocational school.” It’s helped to build his talents and bolster his creativity as a fabricator and a builder, and it seems as though the juice was worth the squeeze. “The biggest challenge was diving really deep into the rabbit hole and believing I was capable of finishing with something I could be proud of and happy with.” Hurdles like the exhaust, or making the front struts fit and work properly, seemed monumental in the moment, but in retrospect, were solved with level thinking and a bit of inventiveness. Roddy elaborates: “I couldn’t be happier with how it turned out. Building my first ever cage and tube chassis was a bit of a stressful episode, but it came out great. Things like going to the nerd store to buy diodes to wire up 7 switches (thanks Justin) was lesson in patience. I can say the biggest challenge really was being a beginner, and trying to do every job correctly under a mountain of tasks.”

It’s a journey worth celebrating, and a result worth preserving on the pages of StanceWorks: the embodiment of what these pages were created for. As an outlet for creative expression, Roddy’s 510 wagon leaves nothing to be desired. As an outlet for honing his craft, it goes to show just how much fun he’s having fun doing it. It’s both a build and a journey that feel wholly and decidedly “StanceWorks” at its core. He’s one of us.