It was nearly two years ago that Rusty was finally unveiled: the cover was pulled back and the latest iteration of a car-turned-legend was shared with the world at SEMA, 2015. However, two years of hard work was poured into the car, only to be followed by nearly two years of radio silence, relegating the car to borderline secrecy, short of the occasional public appearance. But thanks to a bit of coercion from our friends Keith Ross and Jared Houston, we finally let Rusty loose on the streets, proving once and for all that fire can’t kill a car. So, when dealt lemons, I gold plated the sons of bitches and put them on display. I used the opportunity to start from scratch – in every sense – and pull inspiration from every car I’ve ever found badass, from all parts of automotive history, to rebuild Rusty into something unlike anything else. And now, he lives.

[fve]https://youtu.be/Nc3_KZQvd3I[/fve]

Rewinding, it was more than six years ago when the fire happened. At the time, Rusty was partially disassembled. It’s not something I’ve told many in the years since, but I had grown somewhat tired of the then-current look, which was just six months-or-so old at the time. I was hoping to reinvent the car once more. Don’t get me wrong, the chopped-top, body drop, and gold plated wheels were a ton of fun, but at the time, I was crippled with automotive ADD. And after all, we had a thing going… I changed everything about Rusty likely more often than I changed my bed sheets. “Why not keep the changes coming?” I thought. Believe it or not, I planned on painting it. Sort of. Old school red hot rod primer was on my mind, and the thought of rust and patina peering through a flat brick-red top coat was alluring. The Gods of Speed, on the other hand, clearly disagreed.

While working on an engine in the driveway, sparks flew, and before I knew it, my fuel supply for the engine I was attempting to fire up had ignited. Within moments, the garage was engulfed, along with Rusty inside of it, and within minutes, most of the garage’s contents had been reduced to rubble and ash. At the time, in those few heated moments, I knew the car was done. Or, rather, I thought.

Few cars have proved as pissed off, stubborn, and persistent, for better or worse, as ol’ Russ. Together, we’ve been through a lot, and in retrospect, it’s clear that it would take more than fire and Satan himself to take my car from me. But with a shell warped and consumed by flames, it didn’t leave many options for resurrection. By almost anyone else’s standards, the car was as good as dead. However, inspired by the community, friends, and family to ensure the car was brought back to life, I stripped away every preconceived notion I had about what a car could be, and should be. I cleared the drawing board, and decided I’d build the most badass car I could conjure.

It didn’t take long before I knew what I wanted to do. With the help of friend and mentor Chuck Yoder, we took saw blades and plasma torches to the car’s scorched steel, and cut away everything inside, leaving only the skin. With the chassis toast, figuratively and literally, we tossed it in a scrap pile. I dove head first, not into the deep end of the pool, but rather what felt like into the ocean, to build a car completely from scratch.

The build began with the wheels. It seemed an obvious place to start, since as we all know, the wheels can make the car. In Rusty’s case, I took it a step further, and pieced together what I felt was, bar none, the best wheels that could be assembled, and then I built a car around them. Centerlock BBS E57s don’t come easy: the flat-faced motorsport weave has always been a personal favorite, gracing a number of legends of racing history. In my case, the wheels came from a Brun Motorsport Porsche 962, still pocked and chipped from having been raced upon some of the world’s greatest circuits. But once I found the centers, the build began.

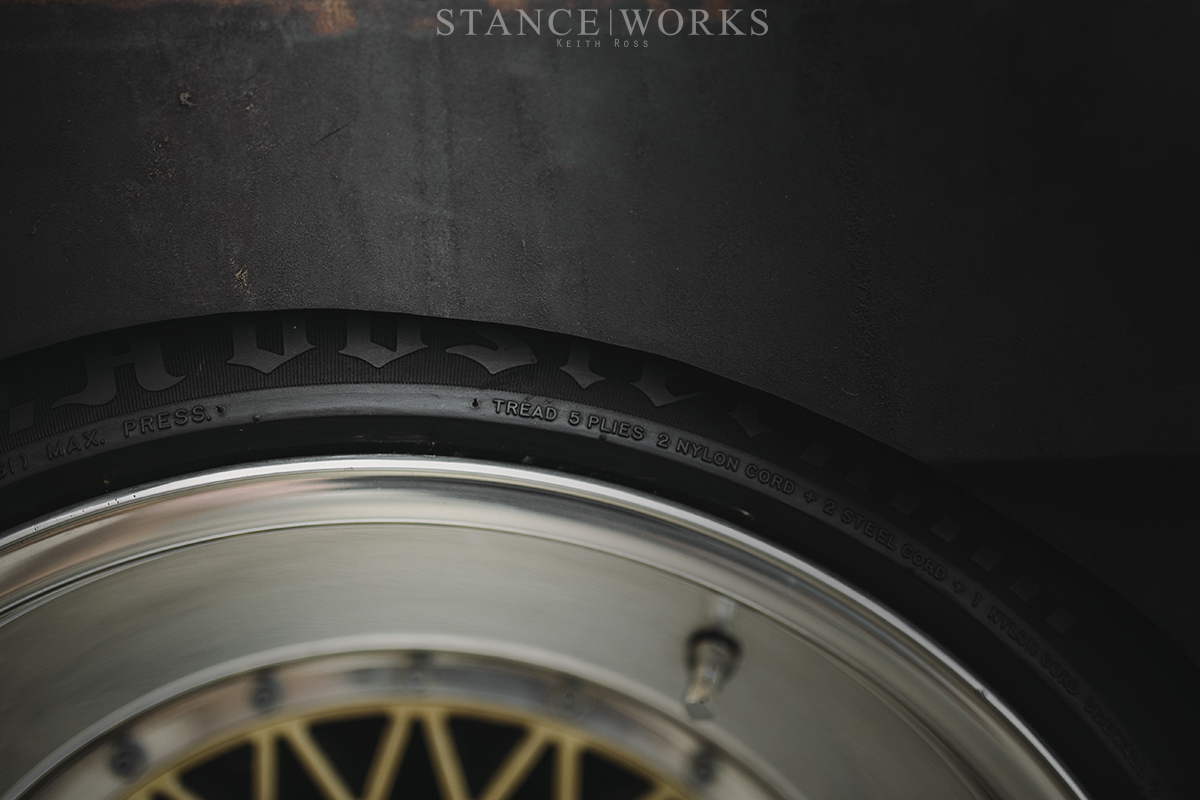

Finding the wheel centers, though, was the easy part. From there, things escalated in my quest to track down original BBS 19″ halves, as raced on a handful of FIA Group 5 cars, most notably the Porsche 935. It took two years to find a suitable set of inners and outers, but once in hand, I was able to flesh out what it was I wanted to build: in short, a Group 5 car from Hell.

The Porsche 935, the Zakspeed Capri and Mustang, the IMSA E21, and the silhouette R30 Skyline – if they don’t ring a bell, stop here. Look them up, and come back.

If you ask me, they’re some of the coolest cars on the planet: gifts from the Gods of Speed themselves for us mere mortals. For me, there’s no cooler race car than one that reflects a roadgoing counterpart, even in the loosest sense. From the enormous fenders and the gigantic wheels, to the low-slung stature and the downright ridiculous bodywork, these cars have it all. For me, there’s nothing better, and so I set out to build my own. With a twist, of course.

The E28 chassis has long been my favorite. I’ve owned 11 of them now, and to me, it’s the quintessential BMW. Its body lines are perfect in my eyes: long, sharp, and clearly purposeful. As a machine, it finds the balance between a sports car and a touring car, and with 4 doors, it straddles the line between practicality and purpose-built. The M5 is the pinnacle of this ideology, where its clear that the minds at BMW’s M division grew bored in 1984, and insisted on shoehorning an M1 engine under the hood of their luxury sedan. Its only downfall is that it was never given the Group 5 treatment.

Wide fenders, an enormous air dam, staggered wheels, and even two doors were all part of my recipe. On the other hand though, it was important that Rusty keep his spirit. Risking a “Ship of Theseus” situation, I wanted to keep as much of the original car as I could. This added to the risk of cutting the car to pieces, and then its skin too, but the risk was worth the reward.

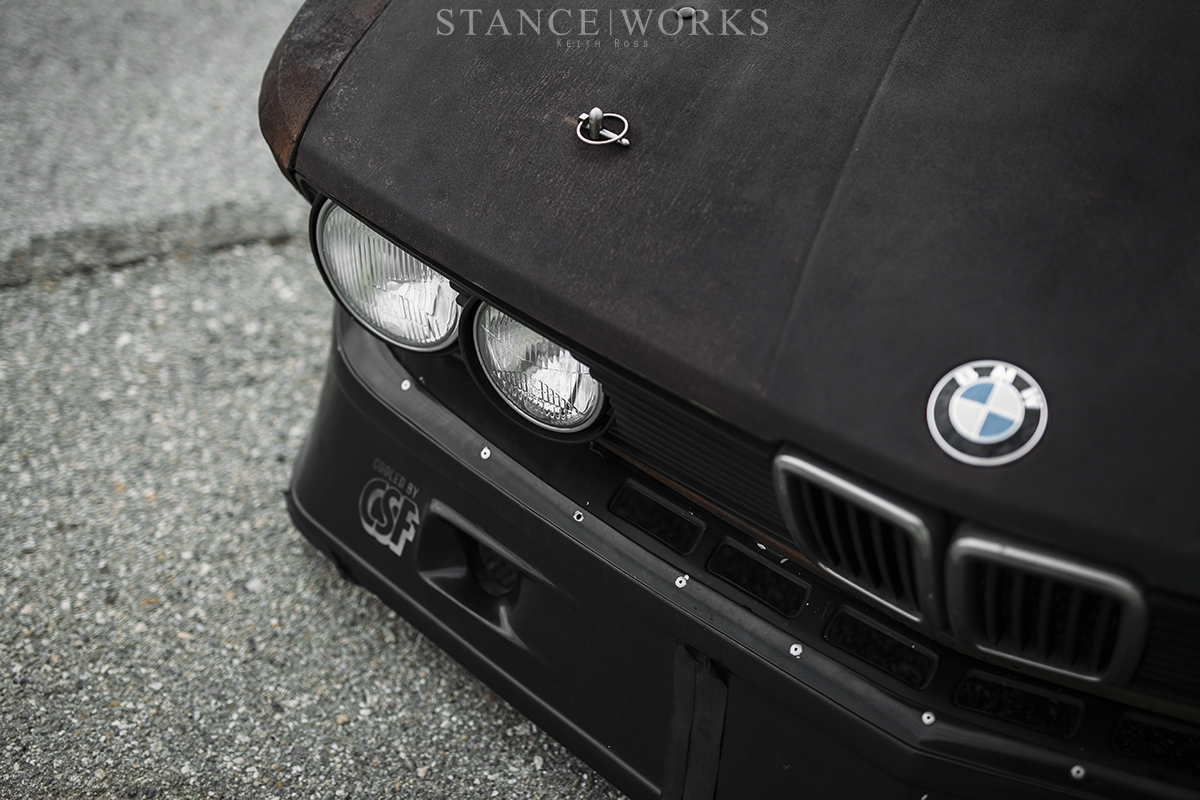

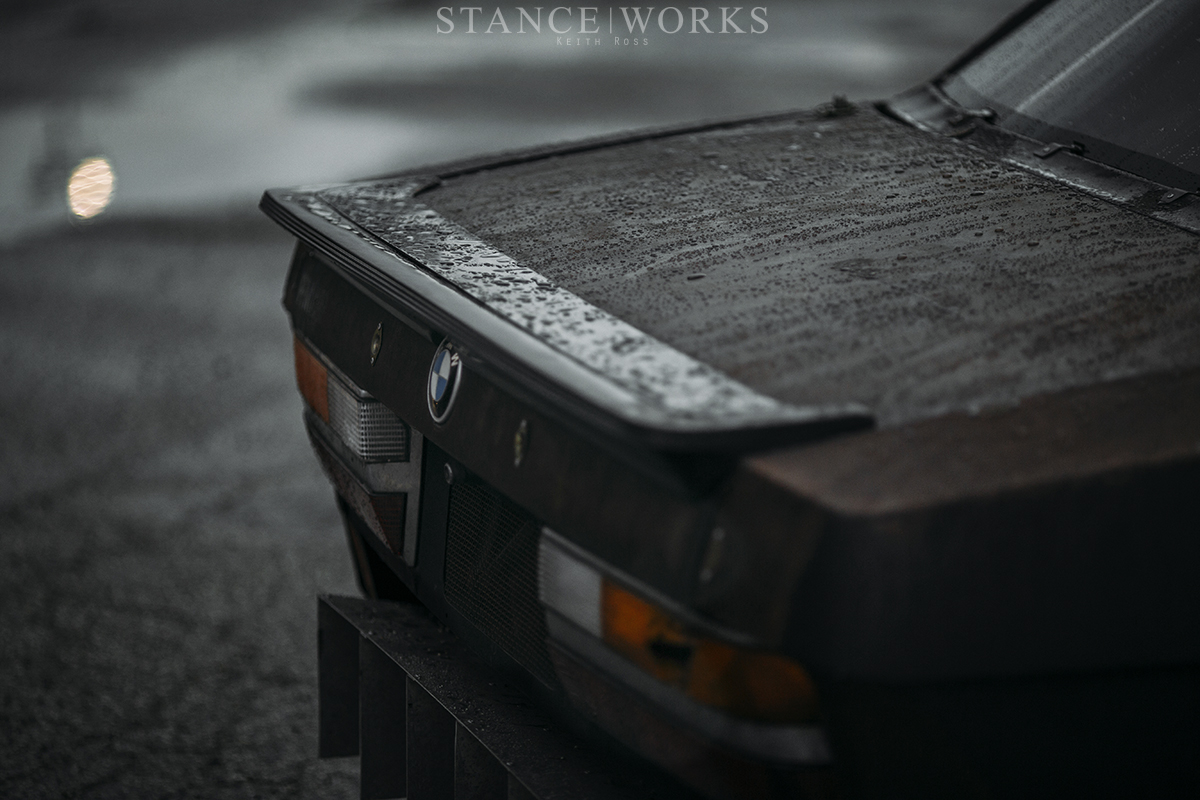

Rusty exists somewhere between the factory race car that never was, and a machine pried from the hands of Hades himself. Shortened a whole foot, and then with the B-pillar moved back, the coupe proportions are spot-on. The chopped top looks right at home, and the fenders are exactly what I’d imagine a Group 5 E28 might look like. Hot rodding, hooning, and vintage motorsports have all found a home here. The hoodline is wide – wider than the original by almost a foot – mimicking the lines of the Zakspeed Capri in all its wide glory. In the center of the car, the doors appear recessed, but that’s far from the case. They remain at their original width, and instead, the car was widened around them, as seen on cars like the 935. The rear fenders are gargantuan, housing the 14.5″ wide rear wheels, wrapped in 345 slicks. The air dam, pulled from an authentic Group 4 E9 CSL, helps complete the look, and the 16″ front wheels and 19″ rear wheels give it that undeniable Group 5 aesthetic. The bodywork still wears its scorched patina – earned by the fires which tried to kill it. I couldn’t dream of bringing the car back to life in any other fashion.

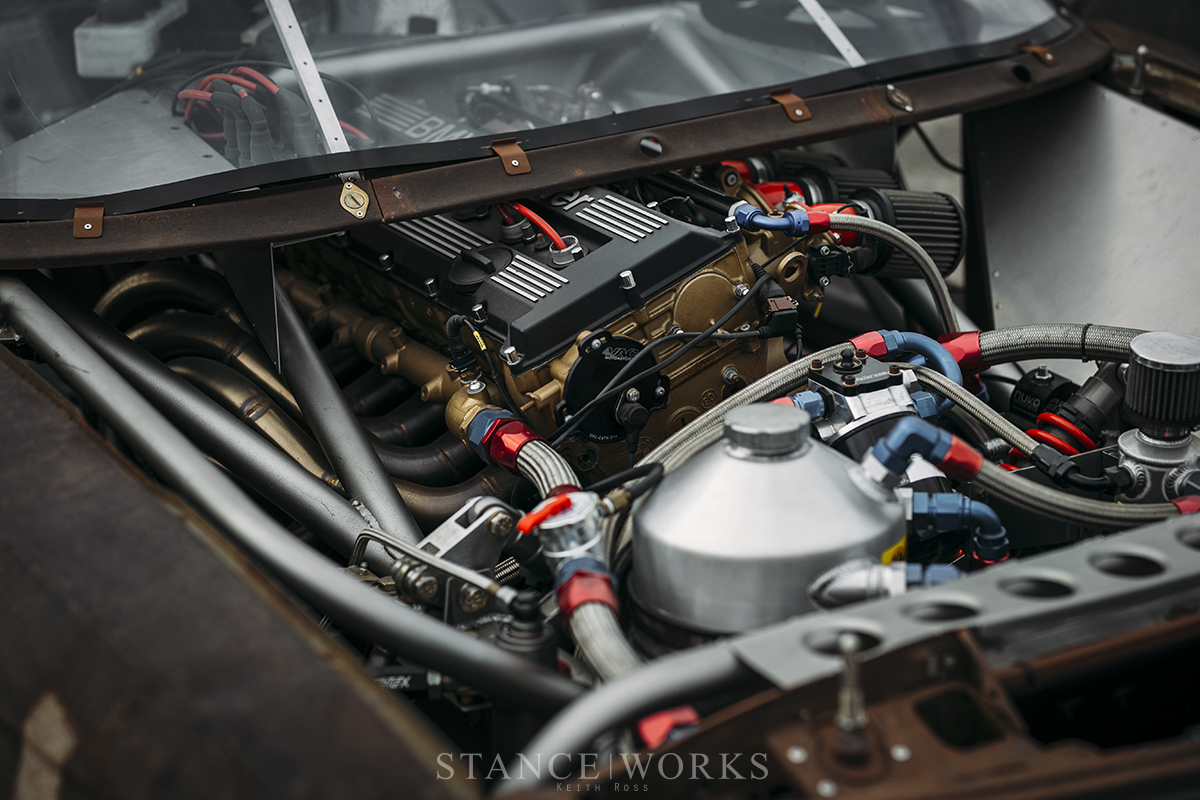

Of course, these days, the car is far more than skin-deep. Underneath the skin that continues to crumble apart is a complete tube-chassis/space frame, built here in the StanceWorks shop. Built from .095-wall DOM tubing, the cagework sprawls throughout the shell of the car, giving support to every component that comprises it. Over the course of a year and a half, Byron Wilcox and I worked to build the chassis by hand. The result is a car that is a borderline go-kart shrouded in a crisped carcass.

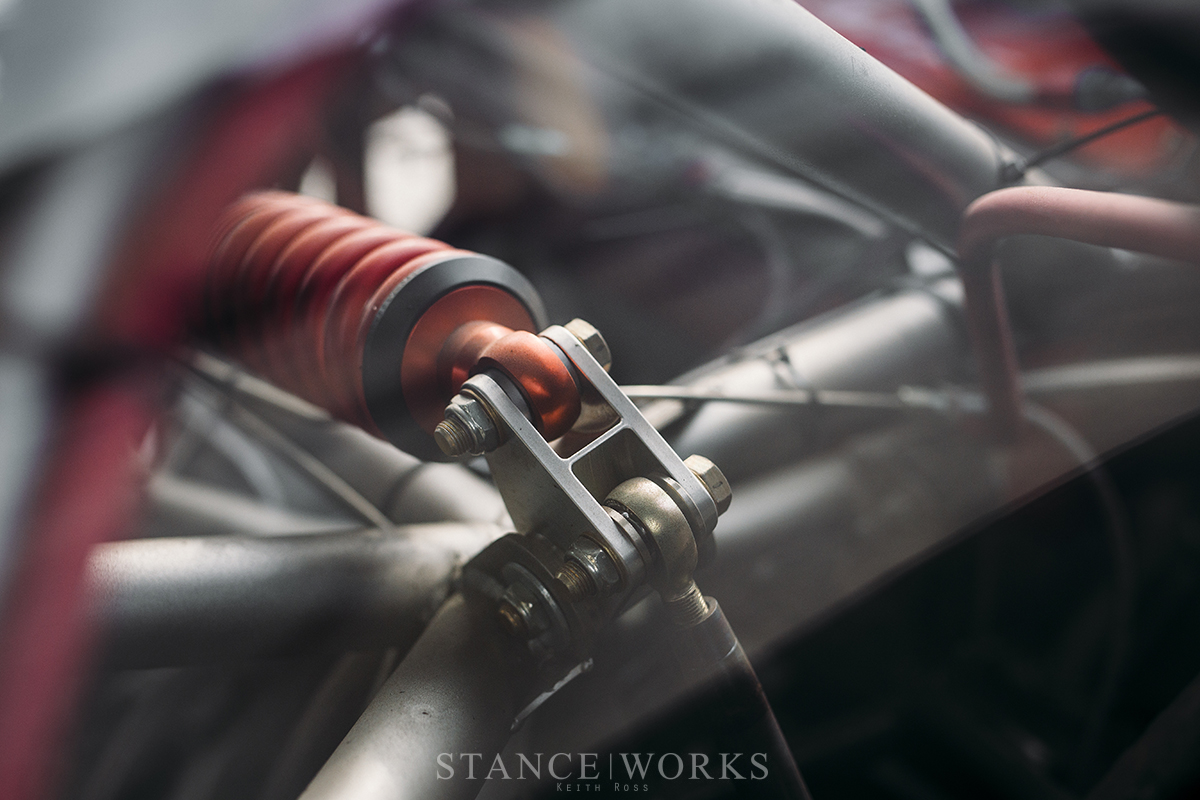

Determined to help bring the car back to life, H&R Springs partnered with me on the build, helping to provide everything needed to make the car roadworthy once more. Inboard-mounted inverted H&R Monotube coilovers are the basis of a completely custom pushrod suspension system, inspired by Formula cars and prototype racers. The rear coil overs are perched in view of the rear window, while the fronts are buried down in front of the engine for the lowest center of gravity possible. With custom spindles, hubs, control arms and more, the car pulls designs and inspiration from a host of classic race cars, and at some point, we’ll put it to the test.

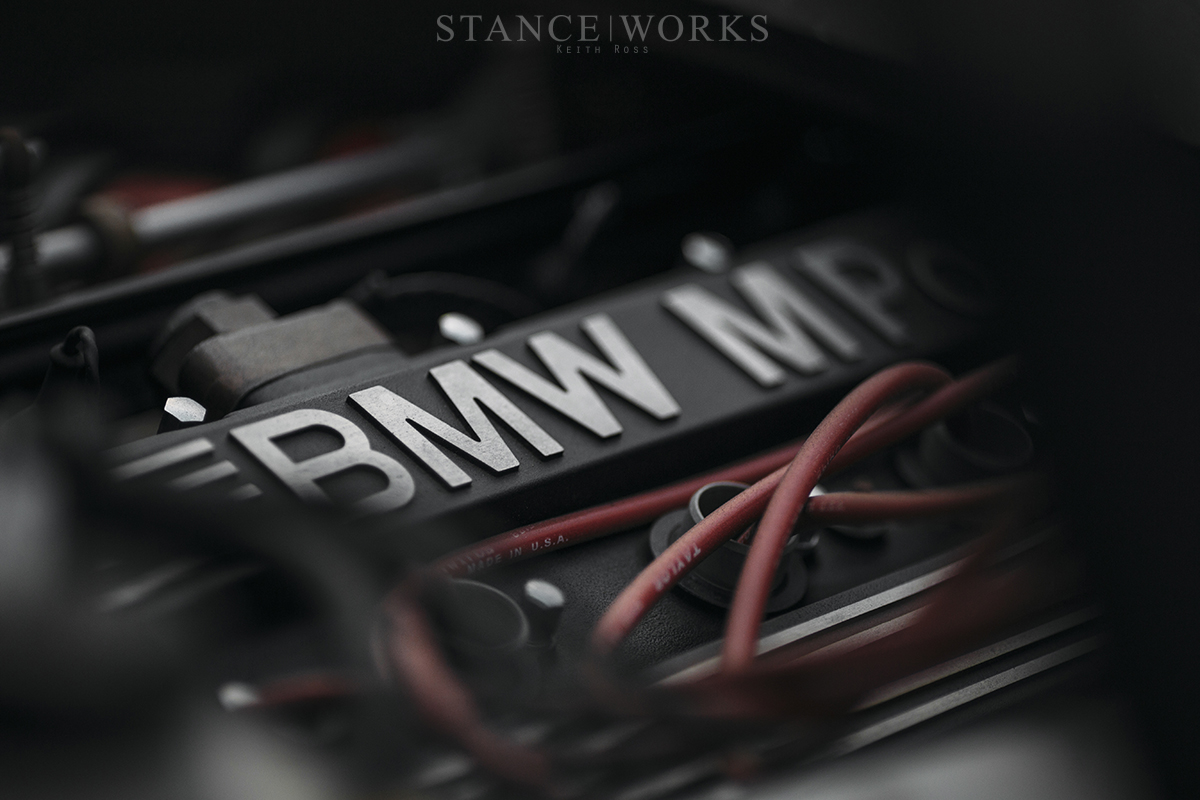

Crammed into the passenger cabin is a balls-out VAC S38 race engine. The engine sits entirely behind the front axle – for a true mid-engined layout – coiled in hundreds of feet of oil and coolant lines that snake throughout the car. At 14:1 compression, running on VP113 leaded race gas, and screaming to 9,000RPM, the engine is almost identical in power output and architecture to an M1 Procar engine. Wanting to keep the car somewhat true to form in terms of what a Group 5 M5 might be like, it was an obvious choice for a power plant, and thus I turned to the best to build it. The engine screams – unlike any other I’ve ever heard – giving Rusty both bark and bite to match the teeth that adorn the side of the decrepit bodywork.

The list goes on. The fuel system features a 15-gallon ATL cell, four total fuel pumps, a Nuke surge tank, and a slew of filters, for one of the most overkill fuel systems imaginable. Air jacks jut from the bottom of the car, hoisting it for service and lift access. The driveline is a custom amalgam of BMW and Ford Motorsports components, routed out through a long-geared limited slip differential. A custom diffuser offers a bit of aero on an otherwise bleak, aero-less machine.

In fact, the list of parts is nearly endless – and while little remains of the former Rusty, he’s back and better than ever. I suppose, today, Rusty begs the question: is it still an E28? I’d say so. And if you’re curious to see more – all of the ins and outs of the car, tune in soon. We’ll be back in a few weeks with a more in-depth look at the details, parts, and pieces that make the car up. While I’d love to share it all at once, I know I’ll carry on forever. So check back soon, as we take the car down to basics, and share everything that went in to bringing it back once more. Until then…