The word “craftsman” is thrown around casually in today’s society. It’s stamped on tools and used all over television. Things are processed and assembled at a furious rate as manufacturers race their competitors to the bottom line. There is a whole generation wandering aimlessly through alleys of mediocrity built by a culture of that expediency. But now, after decades of apathetic consumerism, enthusiasts of hobbies ranging beyond motoring to things like music, furniture, architecture, clothing, or tools, find themselves emaciated with desire to own something tangible. They’re seeking something that moves them, inspires their own passion, and is something they are proud to be a part of. Something “worth it.” Thus, born are the new craftsmen. Men and women filling their own void by building things with their hands and their minds. Chris Runge has stepped into the motoring world with his heart on his sleeve, and has leapt eyes wide open into the world of coachbuilt cars. He is a craftsman in the truest sense of the word.

At 13, Chris was growing up on his Father’s hobby farm. His dad bought him a 1951 GMC pickup to drive around on the gravel roads that scattered the property – it needed some work, but it was the seed of a relationship with motoring for Chris. He mentions “I think I’ve always been fascinated with the structural aspect, whether it’s automobiles, architecture….I’ve been into cars since I was a toddler, and then the idea of how those different things, whether it’s a bicycle, skateboard, automobile; what makes them do what they do?” As time went on Chris got the bug for Porsche. At 18 he bought his first, a ‘78 911 Targa with a steel Turbo widebody. He moved on from there to an ‘84 Carrera, an ‘80 SC, and a slew of 912’s.

Chris enjoyed the 912 and spent time modifying them to go faster. His taste tempered, and eventually Chris pined for an aluminum bodied 356, which is unobtainable by regular guy standards. Chris recalled: “Post World War II, basically ‘47 through ‘51 or ’52, really fascinated me, and the idea that guys were building cars out of scrap aircraft parts, Volkswagens, war vehicles, and then making them race was amazing.” An ad came up on craigslist around this time for a 1967 Porsche 912. Chris dialed the number immediately, and after a short conversation he learned that in addition to the car, there was an estate sale and the sellers husband had many other parts, and a myriad of metal shaping tools. The agreement for the lot was that Chris would use the tools himself, to build his own cars. He filled up his trailer with as much stuff as he could fit, and started out on his journey that would take him to his father’s hobby farm, where he’d begin building his prototypes.

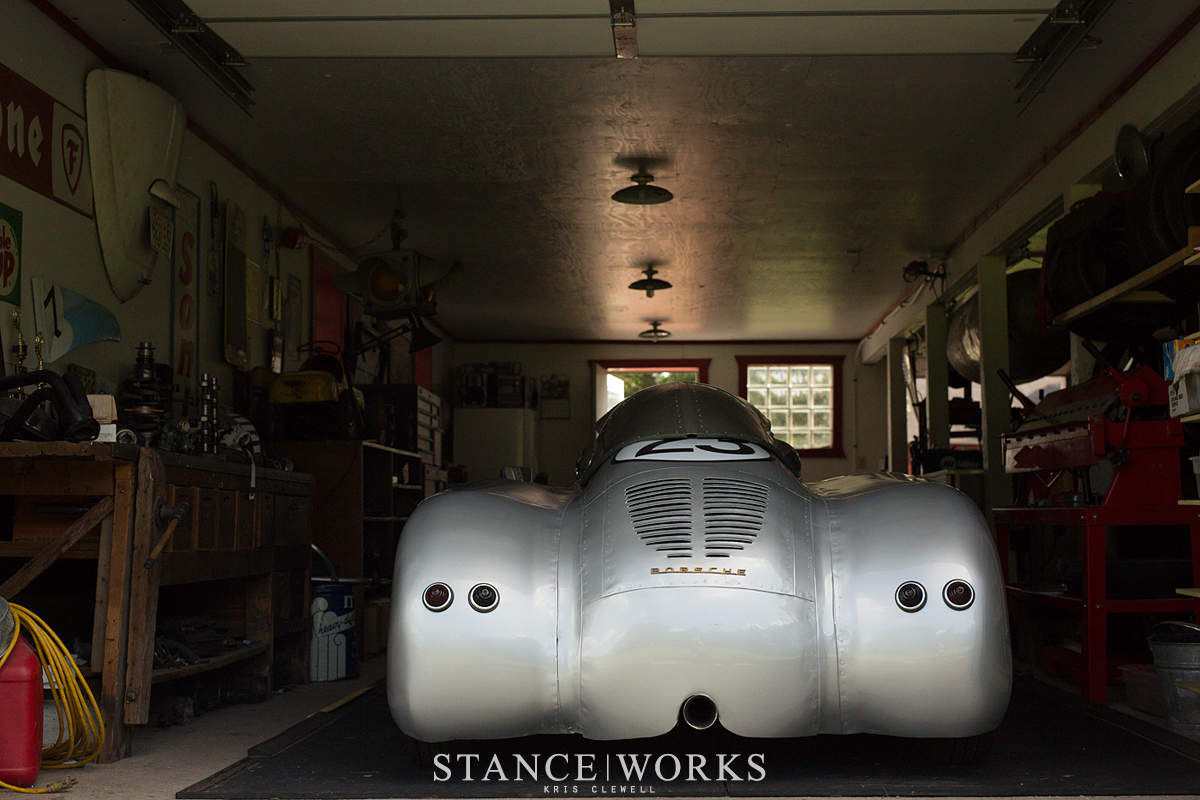

I arrived late afternoon at the family hobby farm. I was greeted by a few outbuildings. One was a brilliant red barn that had been recently refinished by Chris’ father. I was offered fresh home-made tea, and other hospitalities. The mood could best be described as warm. Chris shook my hand vigorously and we made our way over to the workshop through a set of dutch doors. The workshop was bright with Porsche memorabilia and parts. A buck set up high in the corner, its wooden frame stood still hinting of the shape and symmetry of the Frankfurt Flyer prototypes. Much of its design inspired from the Rometsch Racer which resides in a prototype museum in Hamburg. Chris mentioned, “I built that buck in my head probably a hundred times before I actually started making the cuts on it, but I didn’t have anything written on paper. Every piece that’s on it is exactly how I cut it the first time. It all came together exactly how I saw it in my mind.”

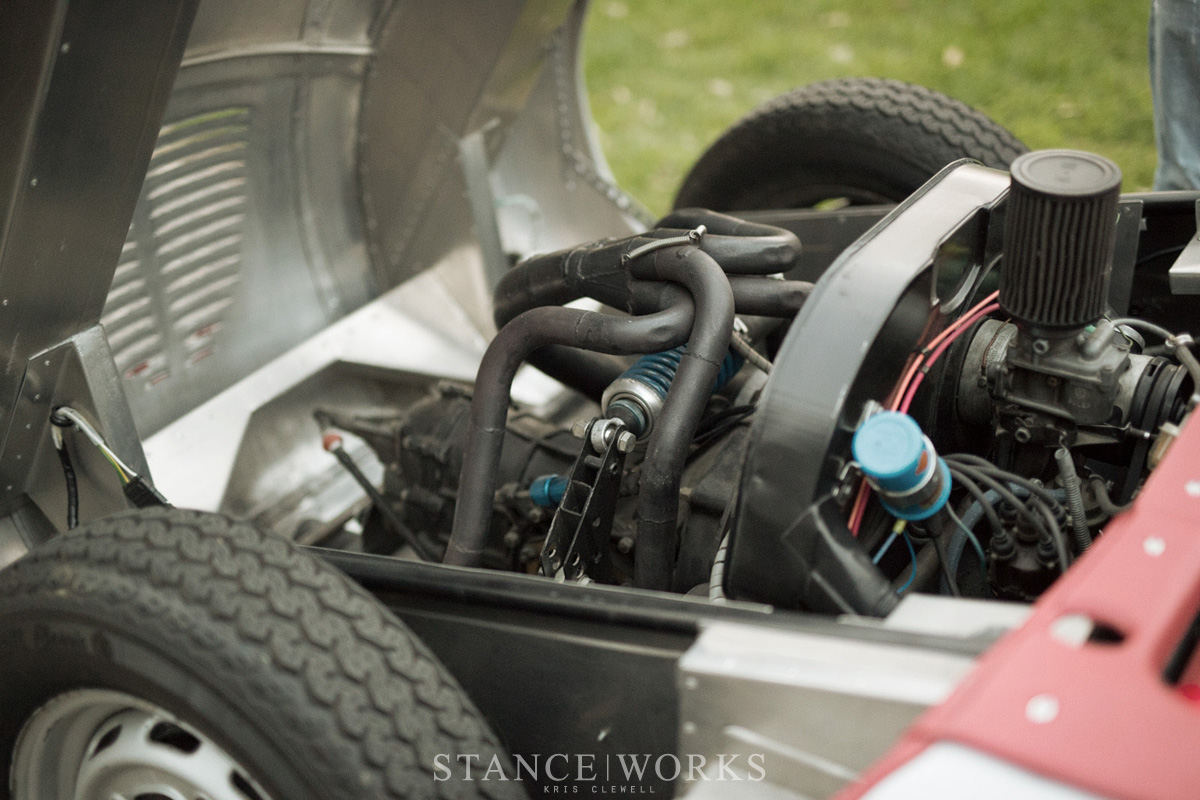

Metal shaping tools that I was unfamiliar with lay about, flanked by the three Frankfurt Flyer Prototypes, 001, 002, and 003. The organic nature of the cars feels at home in the barn. I asked Chris if he could show me what goes into making a panel of the car. He grabbed some paper, laid it out on the buck, and shaped it to the curve of the front fender. Even when making a part that wouldn’t be used for anything, I could see a sense of concentration, stark, and serious, wash over Chris. The paper went as a stencil from the buck to aluminum. Once cut in aluminum the shape was beaten out with a derlin forming hammer, stretching the metal. Ugly and in rough shape, the formed sheet was run through an english wheel. Seeing the curve take shape through the wheel was inspiring. Large dimples were wheeled out into a smooth, organic curve; a three dimensional shape crafted by hand, from a flat, apathetic sheet of metal. Prototype 001 took nearly 1800 hours to finish. The result is as close to a living thing as a machine can be, and it represents a true extension of the mind of an individual.

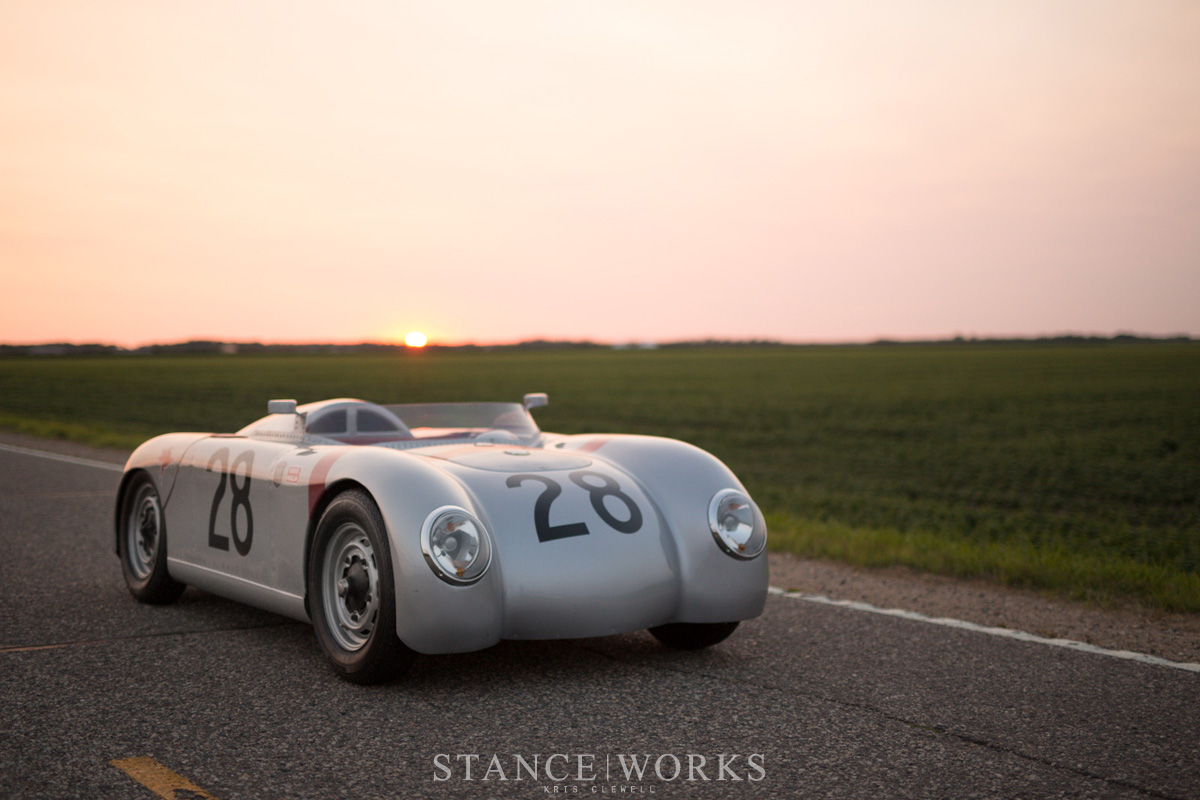

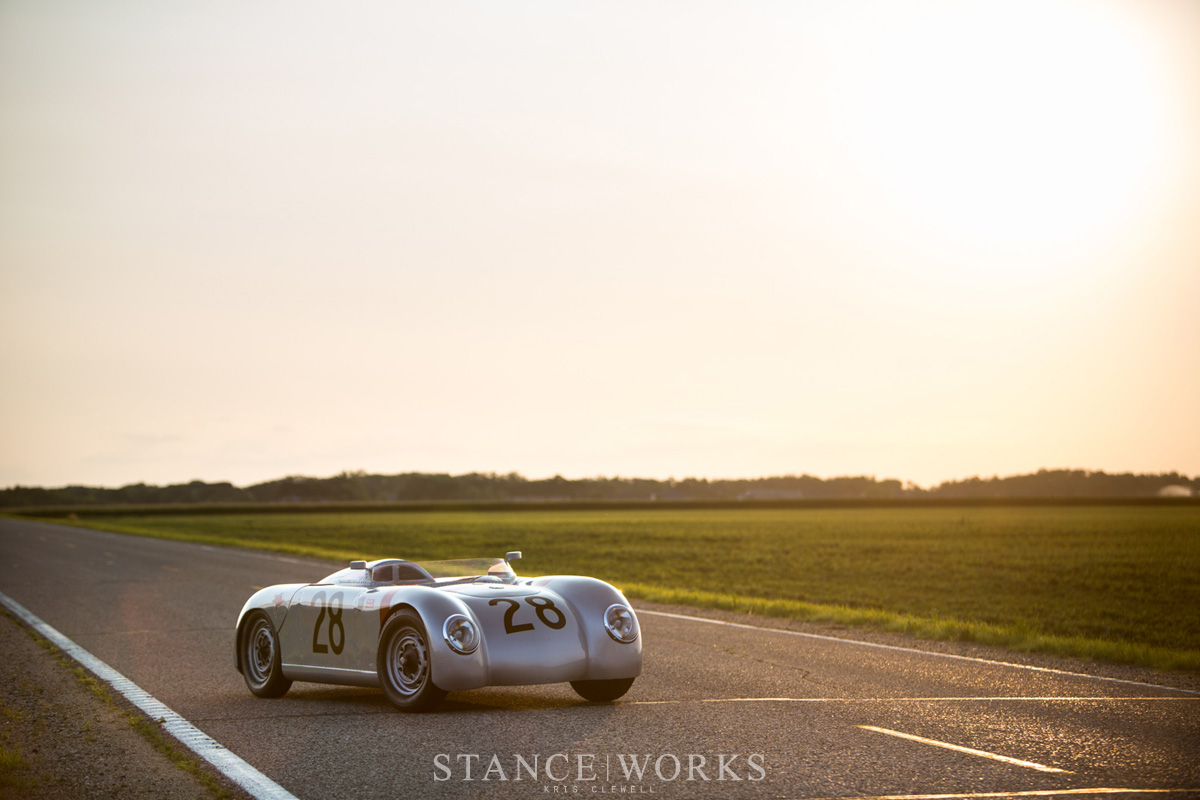

While the Glockler Porsche 51 was something that inspired Chris, he had no intention of replicating it. Instead, he hoped that his prototype could be something that Walter Glockler himself conceived. Walter designed his cars in the late 40’s and early 50’s, and raced his prototypes, eventually gaining official Porsche backing. The prototypes Chris builds are based on a Formula Vee chassis. 002 has a more modified version of the Formula Vee chassis itself. With safety as well as performance in mind, the ladder chassis is made of steel, and with a removable roll hoop. With inch-and-a-half steel for the main structure, there’s plenty of rigidity to support the performance, suspension, and the driver. The rear suspension is a zero-roll single coilover and up front is the suspension from a beetle, dampened with Penske shocks and 944 bump stops. A 1200cc engine is tuned to 65hp, which I found, is more than enough to push around what ends up being a very light car.

Driving something like FF #001 is different than any other driving experience I’ve ever had. I climbed into the single seat and tested out the pedals. The thing that struck me most getting in, was that the man that built the car was helping me get in. He pointed at a few things I immediately forgot and put the roof on over me. At a glance, #001 certainly had all the things most cars have, such as a steering wheel, some pedals, and a seat… The similarities ended with the available operational tools and instrumentation. The faint smell of carburetion and oil was in the cabin as I fired the ignition. The best way to describe what it feels like to drive one of the prototypes is to say that it is a machine. Steering inputs are large but feel matched well to the car. The brakes are firm and predictable. Power is not exceptional, but like the steering, it matches the car well. Attention was required when driving, but it didn’t seem a chore. Driving the prototype is more than just a period of time getting from one place to another. It’s driving boiled down into a concentrate that may not be suitable for all drivers. It’s meant for an enthusiast who can appreciate the craftsmanship, the simplicity, and the unique driving experience. It is a truly special car. The prototype I drove is something you drive to feel what operating a real driving machine is like without distraction.

The Frankfurt Flyer prototypes fill a void in car culture. We live in a motoring world filled with beige sedans filled with plastic interiors and green technology that’s conceived by a committee in a corporate petri dish. Recent enthusiast based cars have engine noises pumped through sound systems and micro-controllers modulating your decisions, be they good ones or bad ones. Chris Runge has stepped in and shown that craftsmanship and passion lives on amidst complacent giants in the automotive industry. His work is an inspiring beacon to those looking for a pure driving experience that has no equivocation.