I’m confident that to any self-respecting automotive fan, the Nürburgring needs no introduction, certainly not if you’re a part of the so-called Playstation-generation. I too, like many of you, have lost hours on end – controller gripped tightly in hand, hunched over in front of a glowing screen, pushing an array of vehicular-shaped polygons around a rendering of the 28km-long circuit. Long before arriving, I knew and respected the ‘Ring.

Despite cruising around on countless ‘sighting laps’, learning the names of all of the infamous sections of track, and mapping the mind-boggling 73-ish corners out in my head, I can count on one hand the number of flying laps that have ended without at least one major detour into the armco.

For obvious reasons, the ‘Ring is even more unforgiving in real life than it is in video game form. The key difference between the two is one of consequence – and this is why the Nordschleife has rightfully earned the nickname given to it by one Sir Jackie Stewart – ‘Die Grüne Hölle’, the The Green Hell to those who spreche Deutsch nicht so gut.

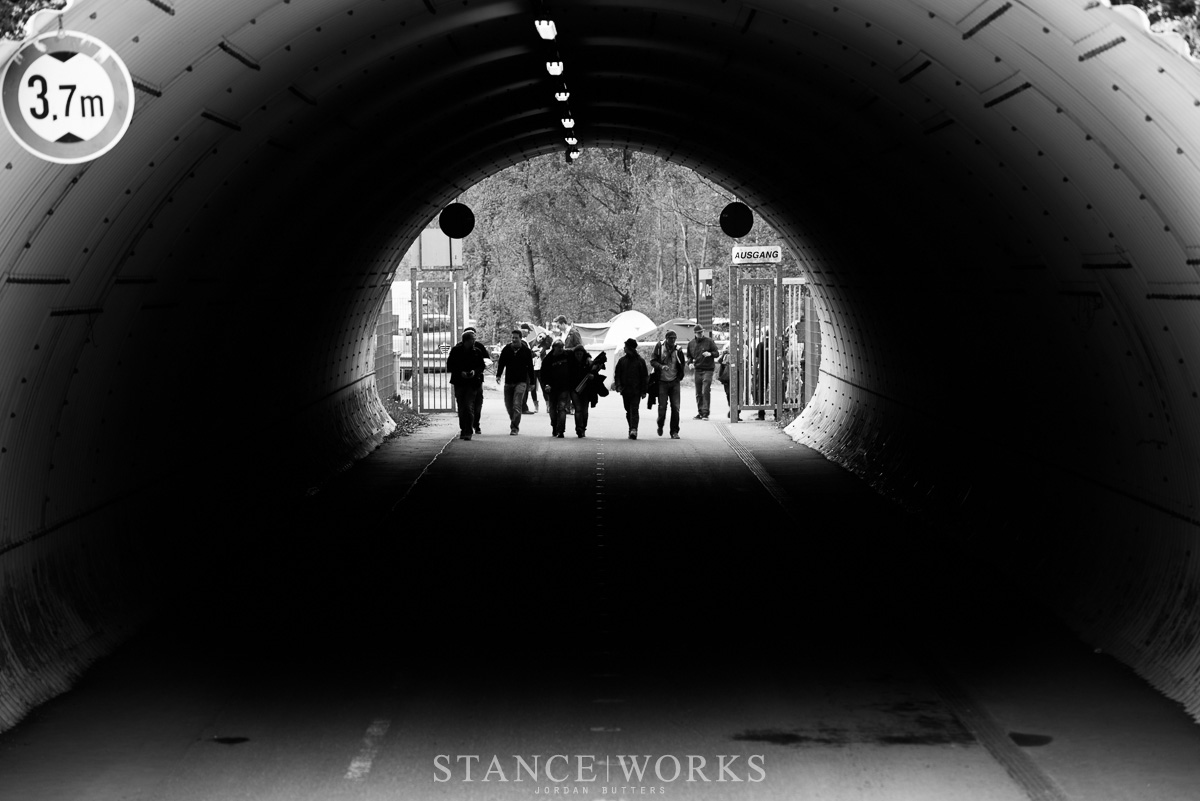

The annual ADAC Zurich 24h Rennen is a 24-hour endurance event. Now in its 41st year, the event is seen as Mecca to a quarter of a million German and European race fans who fill the countryside and forests surrounding the track, turning the entire venue into a giant campsite for the duration of proceedings.

Their passion for racing is unparallelled, as is their passion for drinking into the night and partying hard until dawn.

This was the second time I’d attended the race – the first was back in 2011 when I was there to document the Falken drift team, who demonstrate and run passenger runs at the event, as Falken is a major sponsor of the race.

Back then I was wide-eyed and eager – I didn’t know what to expect and the Nürburgring absolutely blew me away – I was out of my depth, out of my comfort zone and totally unprepared for the sheer scale of the place.

I performed my duties photographing the drift team, enjoyed the partying that the event offered and tentatively dipped my toes into shooting the main GT race with very limited access.

But it was enough – it gave me that little taste of the event and I knew I’d be back.

After not being able to attend the 2012 race due to getting married, returning this year was, without question, something that I had to do. The difference was that alongside my commission to shoot the Falken drift team again, I vowed to forgo the all-night parties in favour of shooting the main event under full accreditation.

That would mean lots and lots of walking, scary drunken campsites, persevering through all weather conditions and not much sleep – but I was prepared, or so I thought at least.

A quick message to those of you practised or versed in the art of capturing light – the Nordschleife is to a photographer what a fully-stocked toy store is to an over-excited 6-year-old. The course is beyond vast, surrounded by and set against so many interesting and unique features that you could return here year after year for a lifetime and still not have explored all of the available angles.

The beautiful thing about it is that even if you’re not able to gain media access, the spectator areas and forest tracks surrounding the circuit offer a multitude of possibilities to shoot the race. I found it a struggle to get anywhere fast, as I was constantly spotting new viewpoints and stopping to capture them.

Thanks to the 1,000+ feet of elevation changes throughout the circuit no matter where you look, you’re almost guaranteed to see the graffiti’d asphalt twisting off into the distance, offering some amazing opportunities for interesting compositions.

There’s two very distinct sides to the N24 race. One on hand you have the sprawling fan campsites surrounding the circuit, laid-back party atmosphere and incredibly positive, chilled-out vibe.

And on the other, the tense, high-energy drama of the paddock and pit lane. This is one of the scariest places to be during the race. With so many cars taking part, two or three teams share each single pit garage and the space in front of. Pit stops and driver swaps are fast and frantic and happen with little warning – the only indicator being a pair of headlights heading your way and a wailing siren in the paddock (which, as it goes off every few seconds, is easy to get complacent with).

Alongside the main event, the weekend also plays host to the ADAC 24h Classic race. Don’t let the name fool you – although it is an endurance event, the Classic is limited to just three hours.

Whilst the field is largely made up of BMW E30s and Porsche 911s, there were some real gems in the line-up, such as this Warsteiner BMW M1, seen here as it crests the hill at the infamous Flugplatz.

One of the main pulls of the N24 is that big-budget race teams in huge horsepower GT cars share the same stretch of asphalt as smaller, privateer teams in more modest (yet impressively kitted out) machines.

This makes the race increasingly interesting to watch, and at the same time, all the more dangerous for those out on track.

The Nordschleife is a tricky enough beast to tame alone, factor in weaving through slower traffic and you’ve got all the ingredients for some spectacular overtakes and the odd coming-together.

Of course get two cars in the same class, fighting for position on the same stretch of road at once and the red mist is bound to descend. In the back of their minds, the drivers have to be aware that the name of the game is endurance, and whilst it’s important not to give up position too easily, the main goal is to complete the highest number of laps within the 24-hour time limit.

During the daytime the Nordschleife is one of the most magical places on earth, especially if you’re treated to a spot of sunshine.

The original track was built in the 1920’s and I wonder if the circuit’s founders had an notion or preconception of just how iconic this hallowed ground would one day become.

I certainly can’t imagine anything like it ever being built again. No two corners are alike and every dip, curve, and elevation change looks and feels 100% intentional. It tests every inch of both the driver and car’s ability.

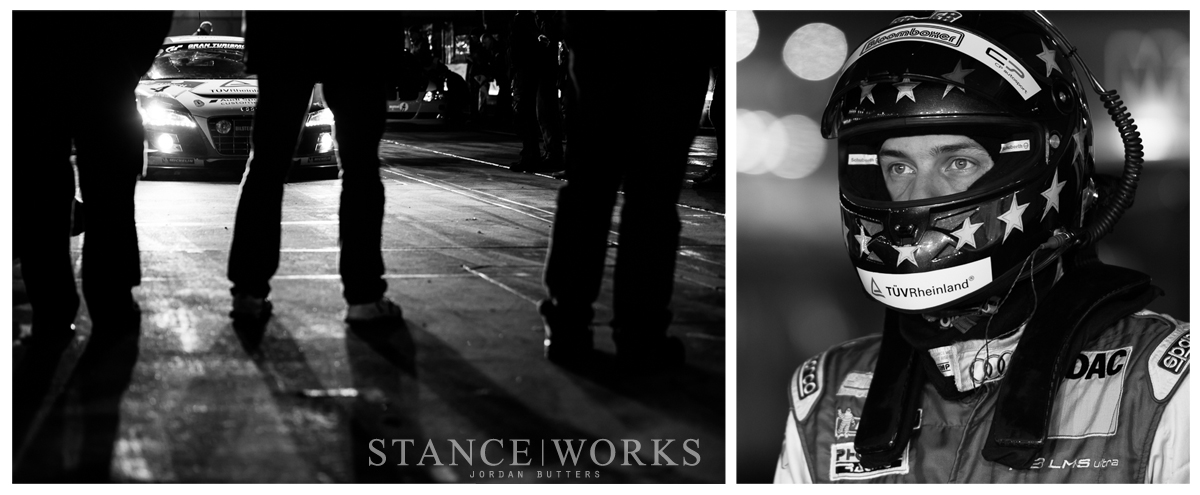

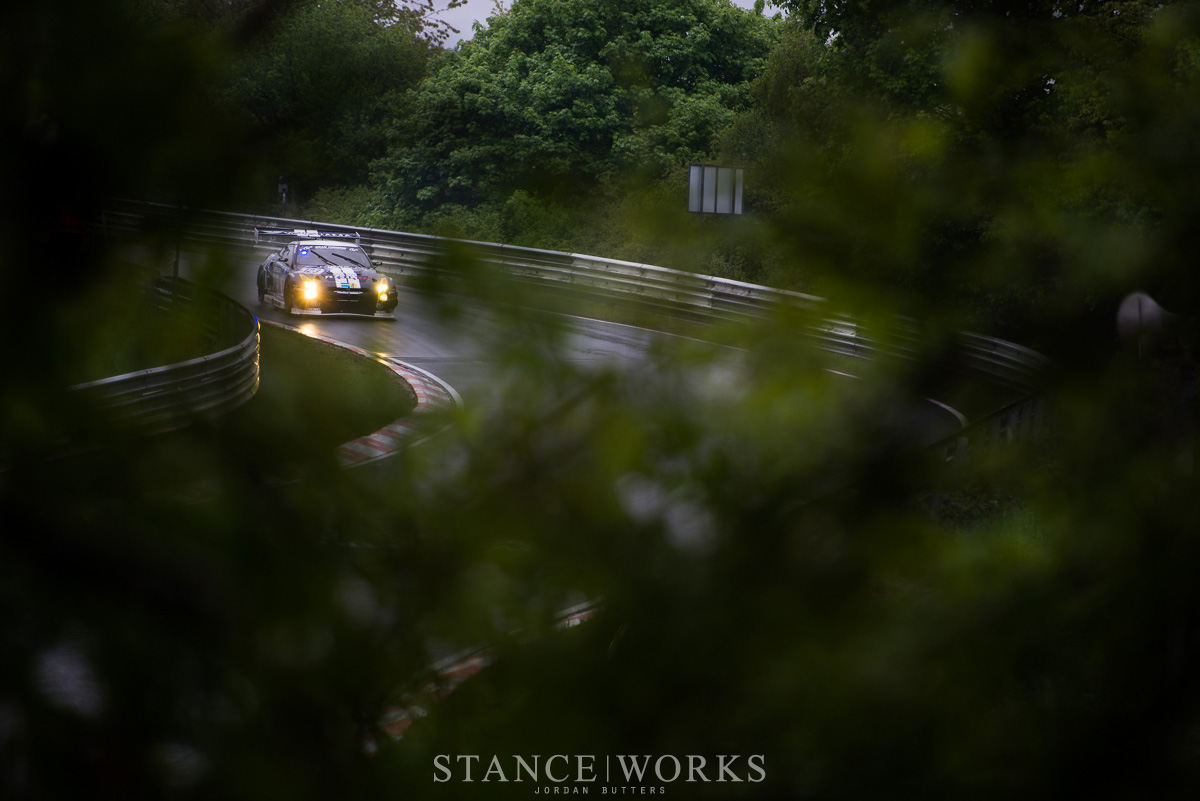

When night descends, the Nürburgring takes on a new life. The huge campsites glow with neon lights and bonfires. Fireworks sporadically head skyward, illuminating the surrounding woodlands momentarily. The track, for the most part, is thrust into darkness, making shooting the night portion of the race akin to photographing a black cat in a coalshed.

Headlights pierce the veil of night. The top SP9 class cars identifiable from a distance thanks to their vivid yellow headlamps and flashing blue warning lamps, designed to let any slower cars know that they should probably get out of the way, sharpish. We’re a few hours into the race and the drivers start to settle in for the gruelling night shift. Fatigue, low light and the Nordschleife – it’s easy to see why this is the most dangerous time during the race.

Unfortunately, this wasn’t an issue that we had to contend with for long this year. Did I mention the rain?

When it rains at the Nürburgring, it rains like it means it. Around six hours into the race, and after around five hours wandering through the German forest, the conditions were pretty horrendous for us photographers attempting to navigate the trackside swamp-like paths near Pflantzgarten. The track was covered in standing water, fog was setting in – I can’t even fathom what it must have been like for those out racing. It didn’t take long for the news to filter around to the nearest marshall’s post – the race had been red flagged due to dangerous conditions and poor visibility.

After a quick stop off at the Media Centre to shake the water out of my camera, I took the opportunity to catch some sleep in the car – it was 3:30am and it would be a good few hours before we would be racing again.

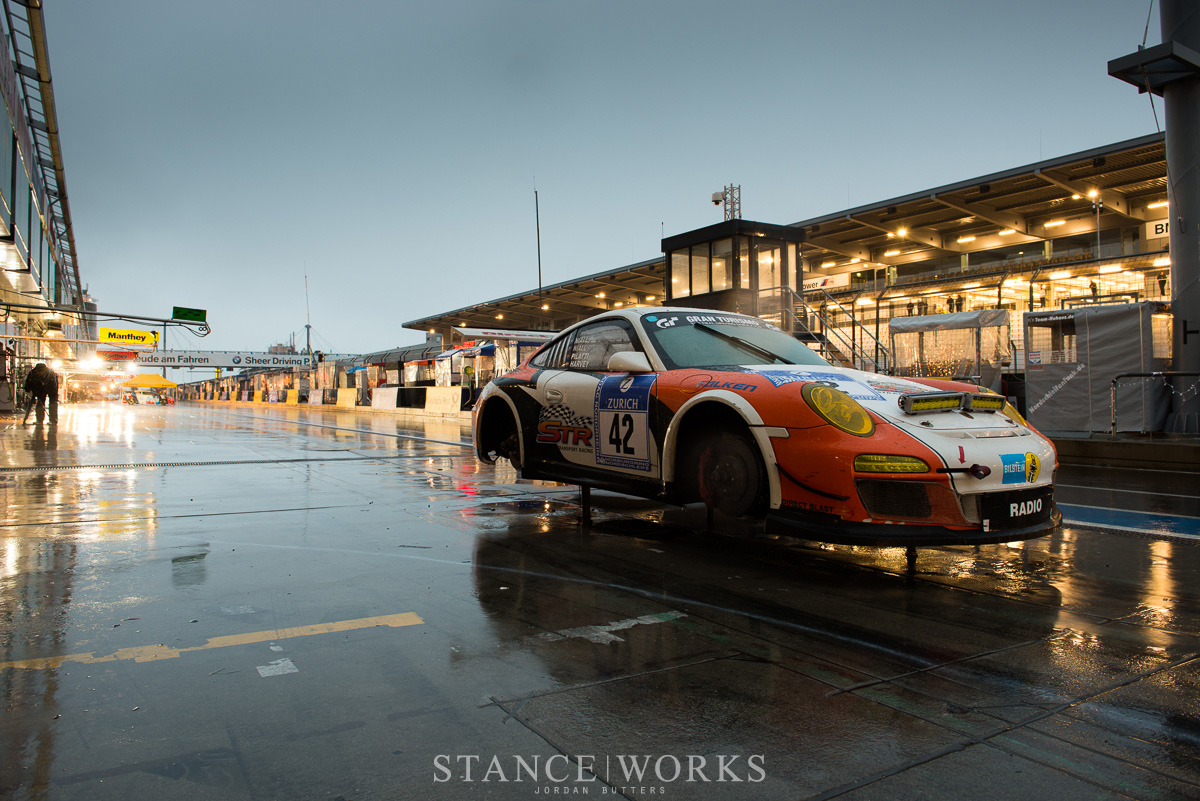

My phone buzzed at 5:00am just as first light rolled around. I decided to take a stroll through the pitlane to try and catch wind of any news of when the race would be back on. Signs of life were few and far between to say the least. It was one of the most eery atmospheres that I’ve ever experienced at a race event.

Whilst some cars were tucked away in the pit garages for the night, worked on, tweaked and repaired, some were left standing out in the rain – poised to go racing again.

Wheels and tyres make for good furniture, and the evidence of a mechanic’s midnight snack is the only sign of life in one garage.

A couple of hours later and we’re racing again. When a 24-hour race is red flagged, the clock keeps on ticking and the rolling restart is staggered by class and takes place under the safety car. Just one lap in and the rain started to fall again – the Marc VDS Racing Z4 is fast out of the blocks, leaving the field behind after just one lap.

Upon arriving at Wehrseifen, the gigantic campsite from the night before is somewhat watered down, evidence of a damp-night’s parting is abundant. The cars push on.

The Schulze Motorsport G35 pops, scraped and bangs as it’s exhaust note reverberates around the forest on the tricky approach.

The dip at the bottom of Wehrseifen is filled with standing water, making for plenty of cool photo opportunities, but a few hairy moments for the drivers.

As the weather eases up, and mist rises from the pine tree-covered hillsides, exhaust notes fill the air once again. The night was too quiet and the ‘Ring is alive once again.

As a photographer at the N24, it’s difficult to keep a track of what’s going on in the race. You hear murmurings from the crowd about who’s in the lead, who’s crashed and who’s in the pits. The action on track is simply relentless, you can’t take it all in.

Coming back to my earlier toy store analogy, I found myself giddy with the possibilities that the circuit has to offer. Whatever game plan I formulated quickly went out the window along with logic and physical boundaries.

I didn’t realise it at the time, but 23-hours of continuous trekking and shooting with next to no sleep had me running on fumes.

I finished my Nürburgring adventure with a 45-minute trek uphill to the Caracciola Karussell, just as the race reached its final stages. The Karussell is quite possibly the most bonkers and infamous corner in the world. No matter how lost I got on the ‘Ring when playing Gran Turismo, I always knew where I was when I arrived at the Karussell. As I approached through the forest I could hear the scrapes and bangs of carbon fibre and metal against the banked concrete corner long before I laid eyes on the track.

I was happy just watching the spectacle at the Karussell. The cars dropping in at the entrance, almost like a skateboarder entering a half-pipe, before hugging the inside of the steep banking and popping out on the other side, throwing a wheel or two into the air.

As the race came to a conclusion, news filtered through that the #9 Black Falcon Mercedes-Benz SLS AMG GT3 had won the race, completing 88 laps in 14.5 hours of racing. This was to be one of the shortest 24-hour races in endurance history, but to those out on track, driving under such gruelling and testing conditions (and those of us trekking through the mud), it certainly didn’t feel it.

It may sound cliché, but words really cannot do justice to this petrol-head nirvana, nestled deep in the German countryside. No amount of preparation can ready you for this track.

If you’ve not yet seen the Nürburgring for yourself, then there’s no better way to put this – do it. Go. Book a flight, or even better (if possible) jump in your car and drive there. The roads surrounding the track are almost as good as the Nordschleife itself; smooth as glass, packed with beautiful sweeping corners and graceful changes in elevation.

As you approach by road there’s an electricity in the air and, whilst you sense your excitement building, as soon as you catch that first glimpse of red and white apex, the looming catchfence, or the infamous graffiti’d surface of the track, you realise what all of the fuss is about.

The Nürburgring is a truly rare thing in this day and age, and the reality of it is that it won’t be here forever, it may be gone sooner than you think, and nothing like it will ever be built again.