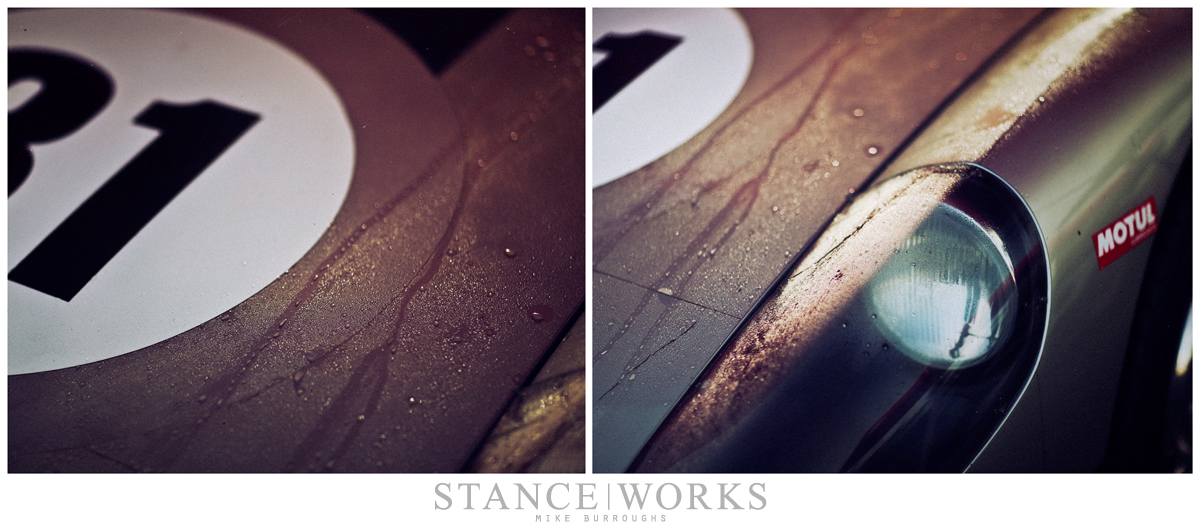

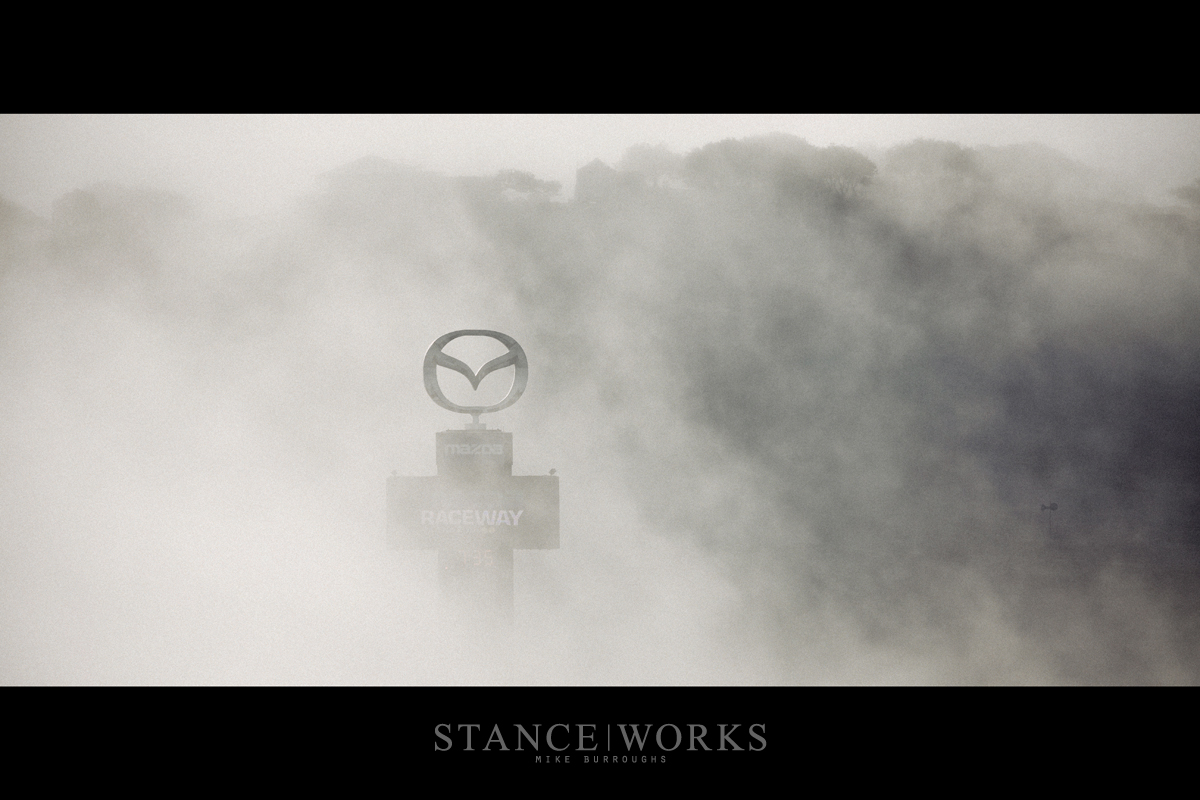

For a while, there’s silence. The distance disappears through the fog on a cold Sunday morning and half of the cars remain covered up, having spent the night outside despite each one’s 7-digit value. The sun has only been up for a moment and morning dew condenses on the nose of a Bugatti type 35 as the owner prepares it for the coming race. Breaking the silence, the high-pitched whir of a starter winds up a thoroughbred, and suddenly, all at once, the paddock of Laguna Seca comes to life.

On April 28, 1887, the first-ever sanctioned auto race was held in Paris, France, from the Neuilly Bridge to the Bois de Boulogne. It was triumphantly won by Georges Bouton of the De Dion-Bouton Company, but the race itself was rather unexciting. In fact, Bouton was the only competitor, but he was certainly onto something. Seven years later on July 23, 1894, the world’s first motoring competition was held from Paris to Rouen, France. 25 cars raced the 79-mile track, finished first by Count Jules-Albert de Dion after a paint-drying time of 6 hours and 48 minutes, making history and igniting the wildfire of Motorsport.

Despite the fact that de Dion wasn’t the actual winner (his car was deemed against the rules and the win was given to Peugeot and Panhard), his importance remains. Today, almost 120 years later, motor racing remains one of the greatest traditions in the world. With each passing year, cars grow quicker, faster, more sophisticated, and more advanced. The evolution of aerodynamics, engineering, and science have allowed today’s cars of racing thoroughbred to surpass the ideas of science fiction just years ago. Their unadulterated speed, outright power, and physics-bending handling characteristics will assuredly be remembered forever. Yet the giants still stand.

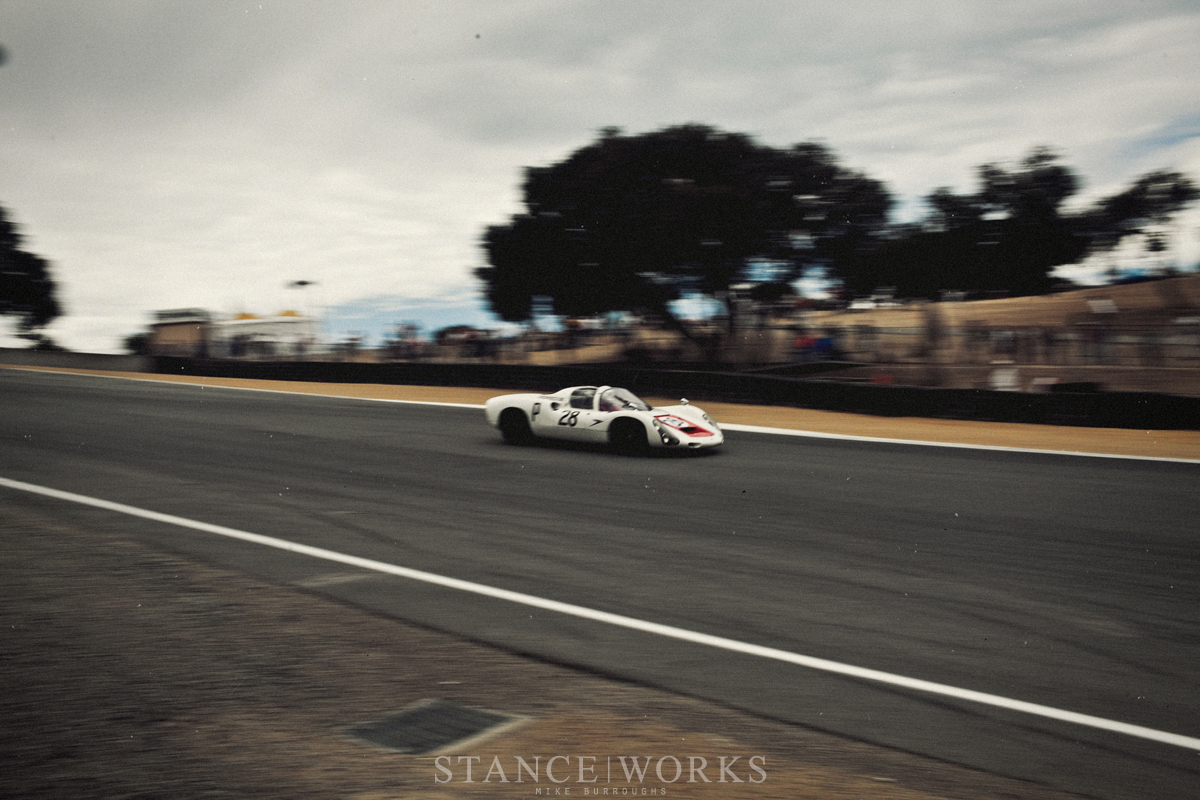

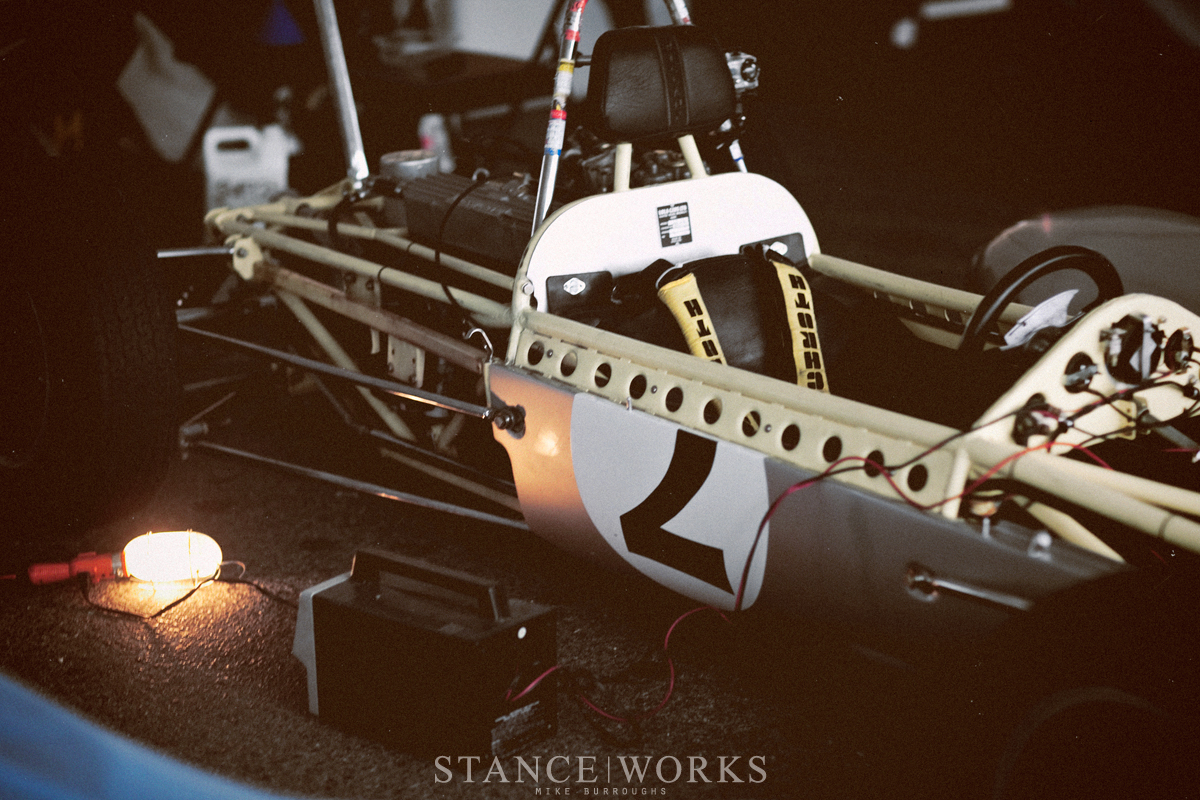

Since 1974, the world-renowned Laguna Seca Raceway has served as a mecca for vintage auto racing enthusiasts. This year, 575 of the world’s rarest, most historic, and most valuable race cars attended the Rolex Monterey Motorsports Reunion. Giants from each era of motorsport participated, taking the cork screw in full force, just as they would have decades ago. From pre-war open-wheeled racers to Grand Touring Prototypes from Group C, everything was present, and it was, without question, one of the greatest experiences of my life.

However, the mere presence of such cars nearly begs a question: “what happened?” Seemingly gone is an era where auto manufacturers brought their racecars to the showroom because if they wanted to compete, they had to sell them to the public. It was a time where any man could find himself purchasing what was nearly a race car, and it was all so that the big names could compete in racing leagues where road-worthy versions of their track-prepped counterparts were required to exist; where homologation rules kept prototypes and skunk-works “supercars” from storming the track.

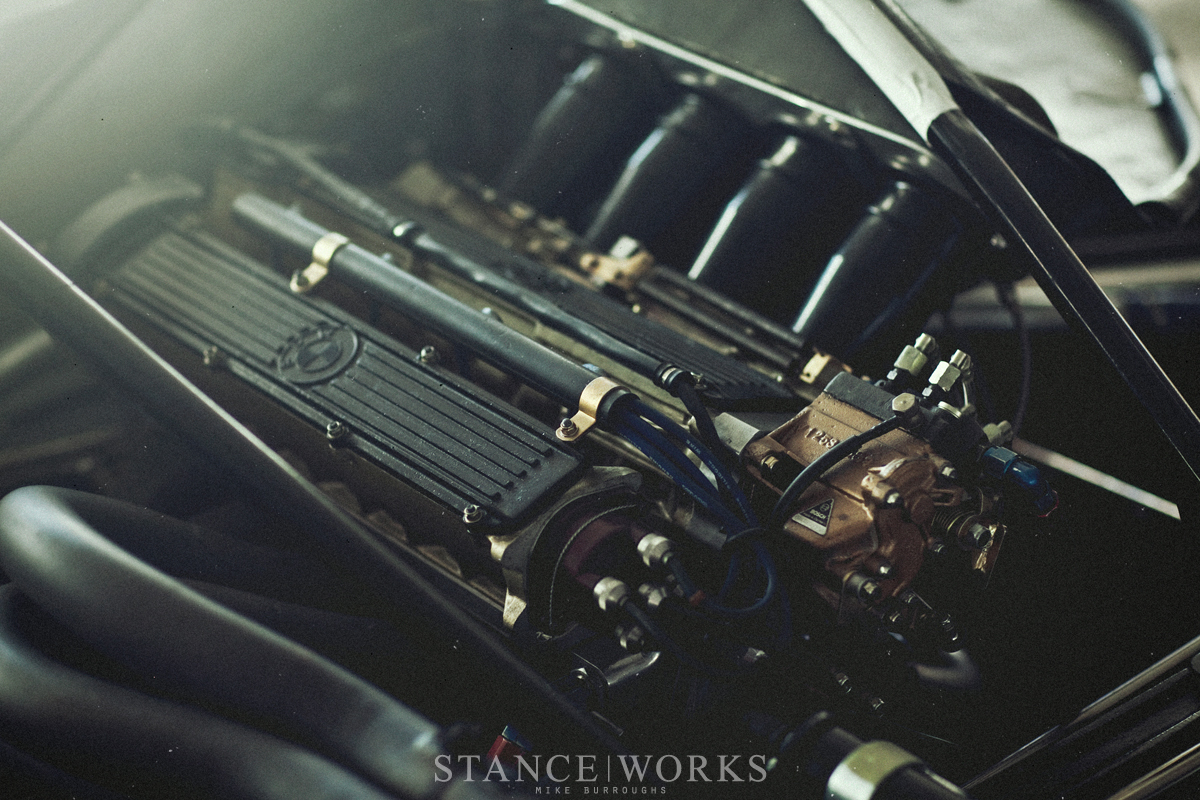

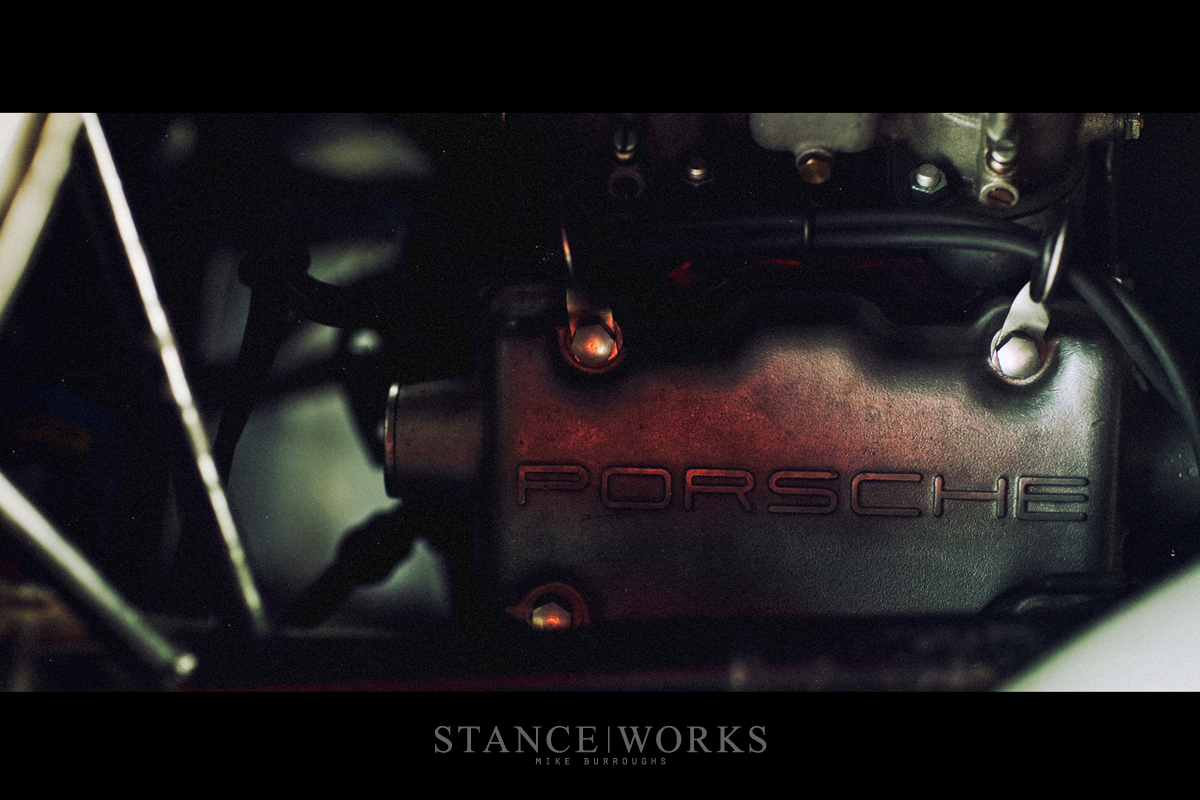

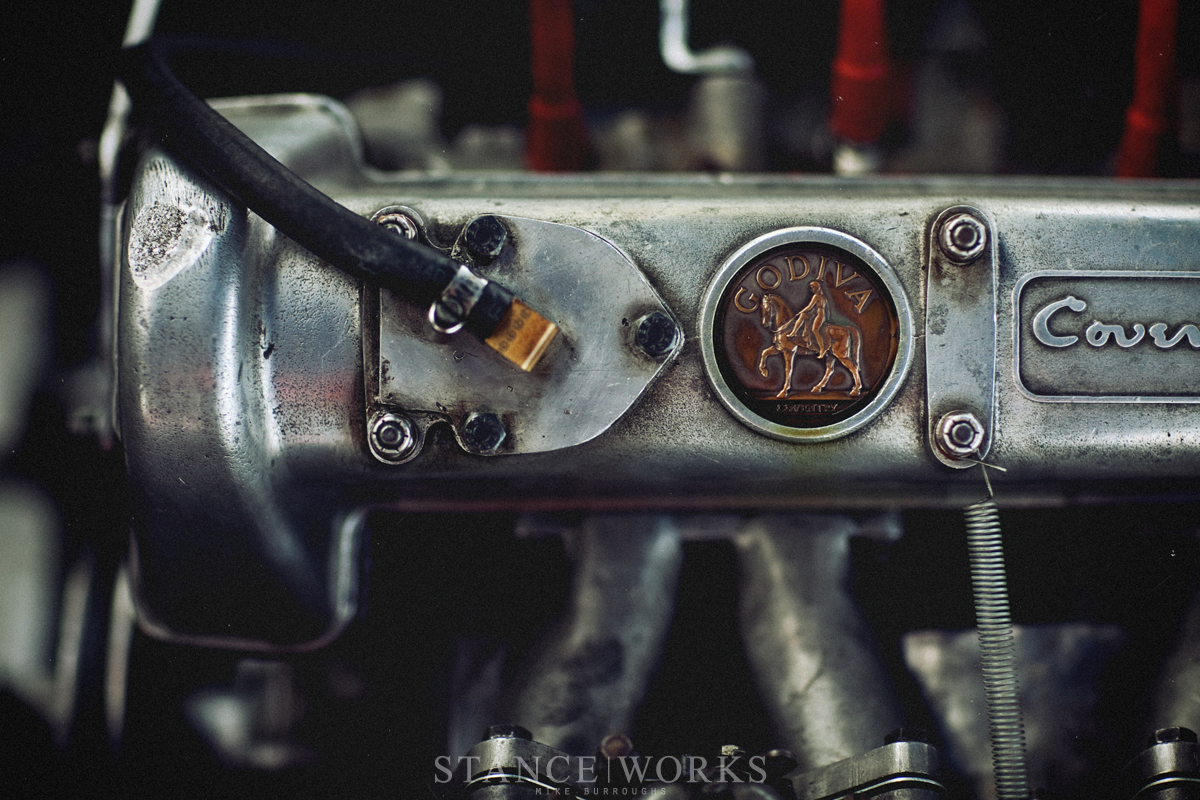

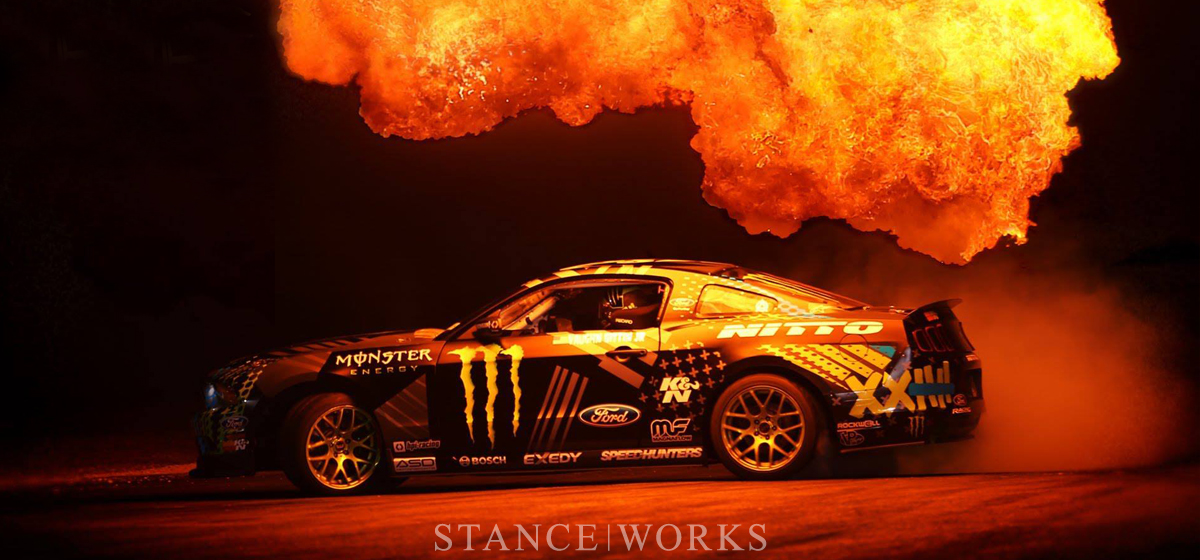

If only through my naive fantasy, these cars came from a time when it was less about the paycheck. It was about the glory of racing; about pushing the limits, extracting every last pony from every last cylinder as they adjusted each throttle body to utilize every atom of petrol; every last bit of air, before the valves closed and the spark plugs ignited what seemed to be an atomic bomb just inches on the other side of the firewall, constrained within the confines of a precision-machined block. These engineers built engines that could spin the earth backwards… that ripped air from the atmosphere, and ruptured eardrums as they spit fire from pipes sticking through holes drilled in rocker-panels and rear valences. They built these engines to race, not to ensure Car and Driver’s top spot in the horsepower wars, or to make bogus claims of the “fastest time around the Nurburgring.” They built these engines to show the world that no one could do it better. If you wanted to, you’d have to work for it. You’d have to out-engineer everyone else, because rules were in place and limitations were set. Aerodynamics didn’t matter and a W16 with 4 turbochargers wasn’t part of the final solution.

It was a time when race classes became legendary for their unmitigated speed…. Where drivers were practically inhuman, because they were simply unwilling to take their foot out of it. When “GTO”, “Gruppe 5”, and “Group B” struck you with fascination, elation, and terror, all at once. Race cars were so impressive it was incomprehensible, inconceivable, extraordinary, and miraculous. For such, they were outlawed. The greatest drivers in the world would lose their lives, not because they were inexperienced, but because they simply couldn’t keep up with vehicles they were strapped into…. and it’s something you just can’t find anymore. The sheer terror of the Group B monsters, muted by common sense and numbed by sanity, shut down and left to the history books.

It was a time when drivers had to drive. There was no TCS, DSC, or any other fancy three-lettered acronyms to define something that only meant a computer was driving for them. It was a time before cars could drive themselves, and if you wanted the best, the only way to get it was with a manual gearbox, not some fancy 19-speed triple-clutch do-it-all paddles of magic. There was never a “power” button to take the engine to maximum potential. The power was always there, all the time, and if you took that turn in the rain with too much throttle it was guaranteed to bite you in the ass.

Tolerances were inscrutable. Valve-trains operated like clockwork. Engines revved into the 5th digit, and at 12,000rpm you’d swear you heard angels singing, harmonized with the screams of straight-cut gearboxes dry-shifting their way down the back straight. And while today’s racing never fails to put a smile on my face, leaving me impressed, the old man’s saying of “they don’t build ’em like they used to” has never felt more true.

It was a time when turbochargers were allowed in F1, and 80 pounds-per-square-inch of manifold pressure was used to squeeze 1300 horsepower out of a one-and-a-half liter four-cylinder.

Back then, maintenance was expensive, because the guy who tore down your engine was someone with utmost deftness and precision. It was expensive because he knew what he was doing. The cost was never to pay off expensive scanning computers, it was for valve adjustments and timing changes that could make a watchmaker go insane. It was expensive because there wasn’t a computer to do it for him. There wasn’t a program written to check his work. There was nothing in place to make sure that a race-bred engine wasn’t going to self-destruct when he turned the key.

Over time, cars came down in weight with the presence of lightweight unibodies and monocoque construction. Today, the average road-going sports coupe weighs half as much as an elephant, and the elegance of low weight and low power is gone in hopes that consumers won’t notice that these “sports cars” need more power than the best of the best just 20 years ago, all to perform half as well.

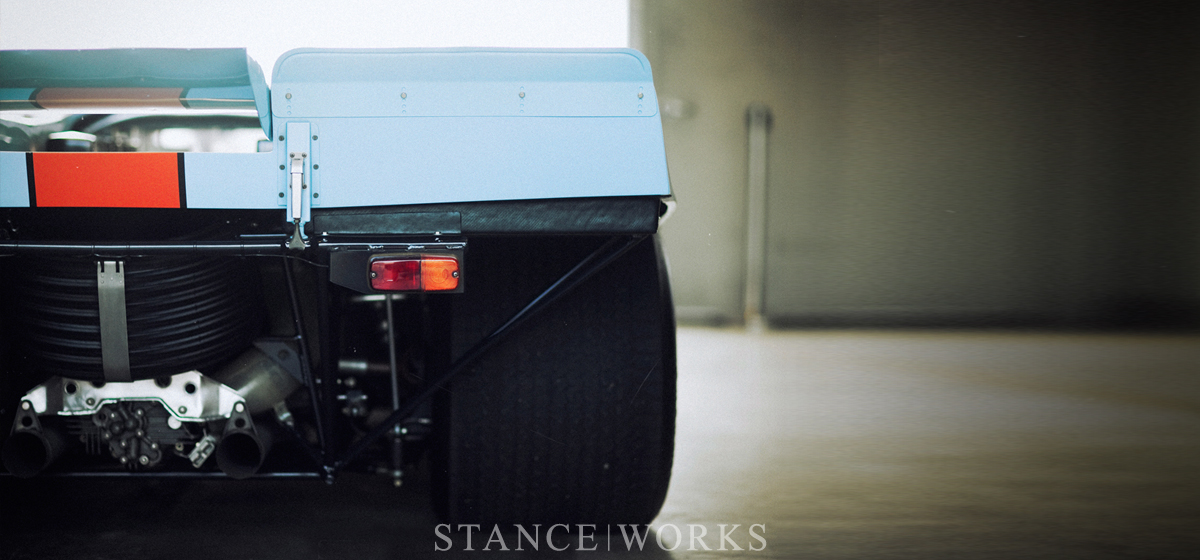

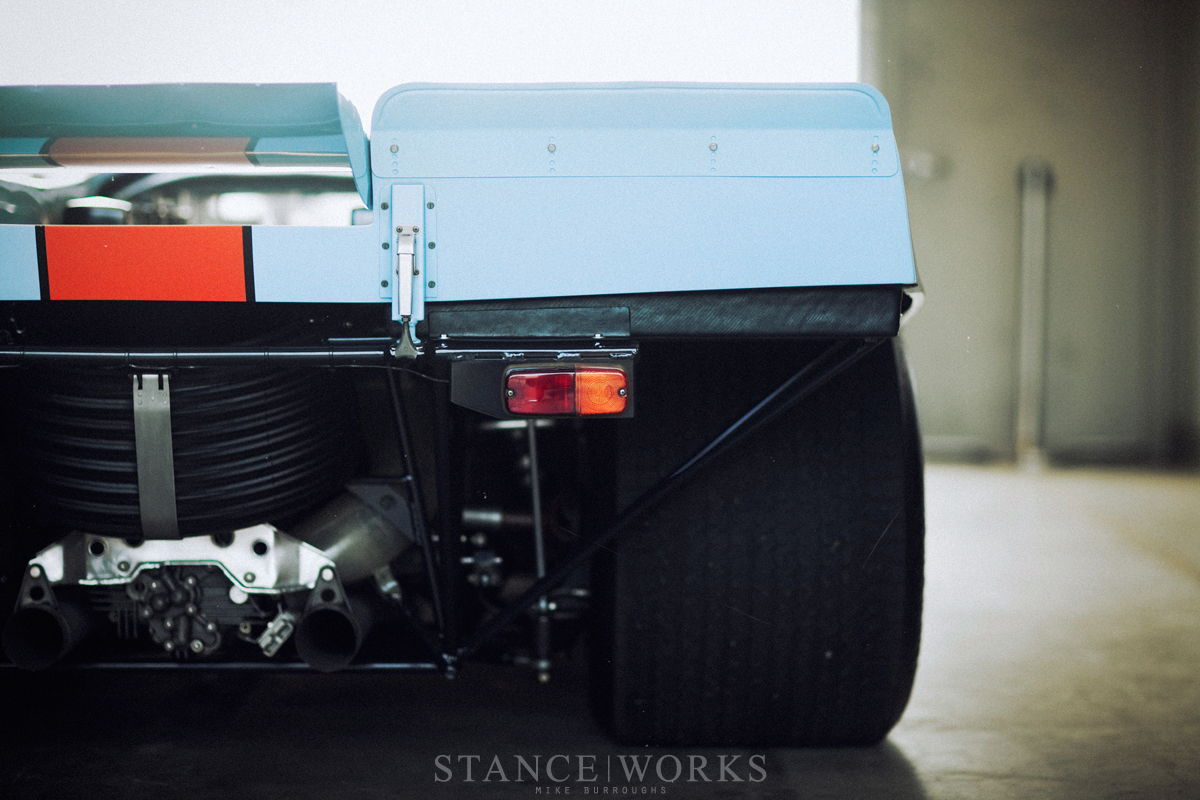

Back then, only screens of thin wire kept low flying birds from being sucked in to velocity stacks, wrapping themselves around monstrous valves only to be spit out in a million well-cooked pieces. A filter only slowed air intake down, and this was racing. If a piston broke free and shot for the sky, it was something to be celebrated. Cars were run as hard as they could be, until they won or they were run dry and the competition was named the victor.

It was a time when race car drivers were the heroes of society, icons of a country, and “players” weren’t hip-hop wannabes on a basketball court. Instead, they were John Player Specials, adorned in gold… and they were magnificent machines. Cars bumped and drafted their way through turns and chicanes, scraping, scratching, and tattering the greatest liveries ever seen. The technicolor brilliance of the era, painted and stuck to steel, aluminum, and fiberglass panels, wrapped around bodylines we could only dream of today. Enormous spoilers, oversized fenders, ultra-low splitters, and new steps in engineering brought something entirely radical to the world of automobilia.

If only over-glorified by my inexperience and youth, I can’t help but wonder. Through the dust and grain of the film that captured the most significant races in history, something different can be seen. Fans by the tens of thousands crowd the perimeter of the track, their screams and cheers almost drowning out the cries of the cars themselves. When it was race day, countries came to a halt, for it was a chance to witness the clash of the titans, to witness a battle of nations, a spectacle more uniting to the populous than the Olympic games.

It was a time when manufacturers seemed like Gods, taking the roles of the likes of Ares and Mars, endlessly pursuing victory and perfection. The names, sponsors, colors, and liveries were worn like family crests atop armor. These accoutrements are engraved in history, signifying the greatest warriors of their time. Names like Marlboro, Rothmans, Martini, and Gulf, immortalized by their success and decoration. None were afraid to tout their success, as it called for a greater challenge, all in the name of pushing motorsport to its limit.

Yet despite where we find ourselves today, enthusiasm has yet to wane. For one weekend per year, the timing tower of the Mazda Laguna Seca Raceway rolls back, and the greatest cars of their time are raced head to head. Their individual values are ignored; multi-million-dollar museum-worthy pieces share the tarmac. They’re driven as hard as their creators intended, put through the paces and rigors of race day.

To walk on the asphalt amongst these legends gives the weekend true significance in the heart of an enthusiast. Each car present has a documented history; no replicas, no phonies. These are the icons of the sport, the ones our fathers watched race when they were our age, the ones we’ve seen photos of in archives and memoirs alike. The cars we’ve seen strewn across the web, idolized as though we’ll never be lucky enough to witness their past greatness… they live again.

And it’s that realization that carries the most weight. Today’s racing passion is no less important, no less prevalent, and no less powerful. The cars of today will be remembered forever, just as the cars in front of you now. The post-space-age technology and design of the 2012 Formula One field carries the sport forward still, continuing their own footsteps down the path these historic machines have laid forth. The manufacturers whom are still driven by the enthusiasm of the sport incorporate the sciences into crafting the ultimate in automotive technology. Today, shaving nano-seconds off of lap times means more than ever before, as we approach the summit, the pinnacle of motorsport, the barrier to which nothing can become faster.

Drivers like Sebastien Loeb, Sebastien Vettel, and Tom Kristensen will be defined as the greats of their generation, standing beside the names that define auto racing as a whole. And now, we can consider ourselves lucky; we may not lose them, racing may not take their lives as it has so many in the past. The great racers who have lost their lives in the heat of competition have seemingly sacrificed themselves, promoting new steps and measures for the safety of the sport… Now, it is a rare day that these extraordinary drivers fail to walk away from their mistakes. Motorsport still grows.

Though times are changing, the sport only continues to evolve in a positive direction. The cars of today will earn their place among the ranks at the Rolex Monterey Motorsport Reunion, once they too have been retired and the sport takes its next step forward. This year comes to an end, solidifying an entire generation that can only be described as the best in motorsport. That is, until next year, when the next round of greats are written forever into the history books, inducted into the hall of fame that is historic racing. Years from now, we’ll see today’s best held among the legends from a century ago. We’ll point at them and say “they don’t build ’em like they used to.”